When one encounters Giovanni Anselmo’s “Invisible” in a new exhibition at Washington, D.C.’s Hirshhorn Museum, it looks like little more than an old slide projector, whirring lightly and sending a beam of unimportant light nowhere in particular.

Hold up a hand about four feet in front of it, though, and the piece (along with its wordplay title) comes into view. The projector is shining the word “visibile” (“visible” in Italian) in block letters of light. The artwork remains invisible until museumgoers actively try to see it.

“Invisible” is part of “Le Onde: Waves of Italian Influence,” a new exhibition at the Hirshhorn that explores how different 20th-century artistic movements affected one another in Italy and abroad.

Curators Mika Yoshitake and Kelly Gordon (who is no longer at the museum) explored “Italian avant-garde art and thought of the ’20s futurist movement on down to the art of ’60s,” said newly minted Hirshhorn Chief Curator Stéphane Aquin. “The narrative that they drew through art history was very fine and connects a lot of dots that very few art historians have previously connected,” he said. Many of the works on view are rarely seen publicly.

This new narrative line deals in part with how the American vision of modern art history differs from the European, Aquin explained. “One of the merits of this exhibition is to … assess the reconsideration by recent art historians over the past 10 years of artists that had been overlooked, mostly in the U.S.,” he said.

“In the common understanding of the grand narrative of art,” Aquin said, “the Americans had stolen the idea of modern art from Paris, and what really counted was the great American epic of conceptualism [and] minimalism.”

This, Aquin said, was “to the detriment of these amazing European artists who were very finely and very subtly and very intelligently exploring various key aspects of what modern art means.”

The exhibition can be seen in part politically, having been co-sponsored by the Italian Embassy in Washington. “The show … assesses this moment in art history where we can return to those pieces by the overlooked artists and see that they were meaningful,” Aquin said. “There’s a great story there.”

These artists include Anselmo, as well as Italian futurist Giacomo Balla, French op-art practitioner Yvaral and one of the cadre’s unofficial champions, Lucio Fontana.

Le Onde 3

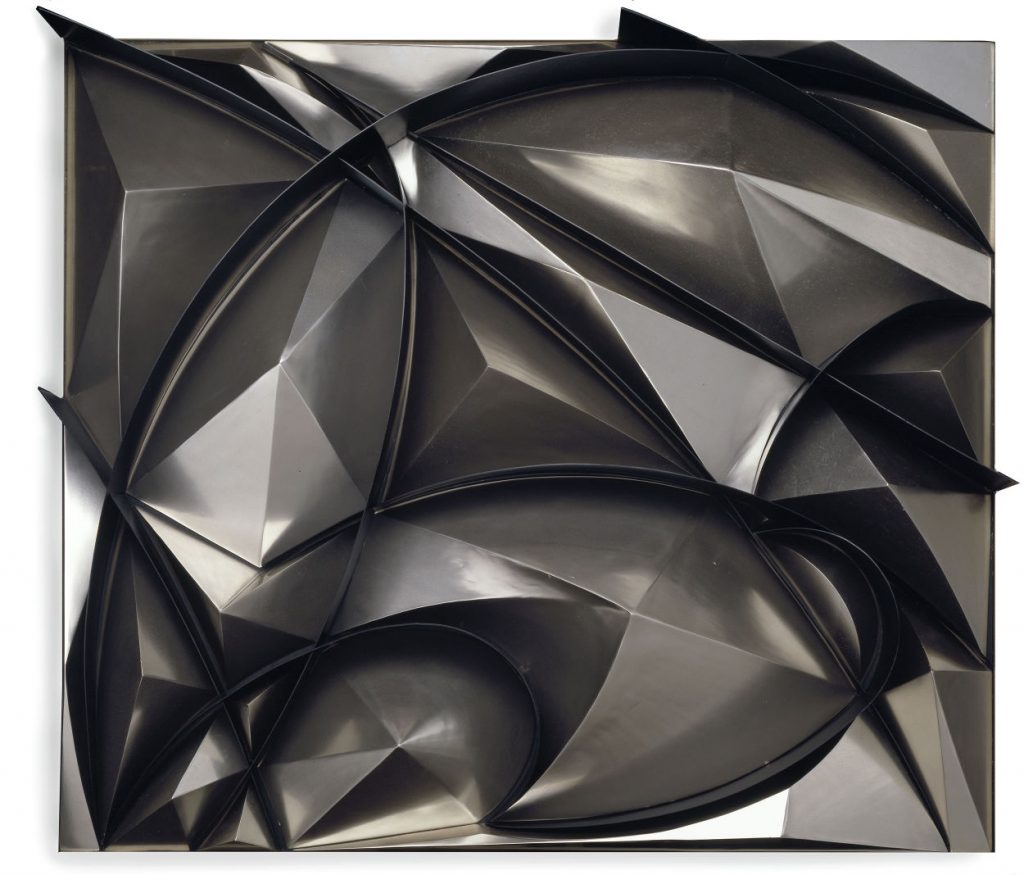

Balla’s “Sculptural Construction of Noise and Speed” (a wall-hanging mass of jumbled, 3-D geometry) is just that: fast and industrial, slicing like a lightning bolt and echoing in metallic forms like thunder.

In “Determinism and Indeterminism,” Julio Le Parc suspends plastic squares on strings in front of a whitewashed wooden background. The transparent squares twist idly and cheerfully, reflecting light onto the floor as busy, bustling splashes of light.

“In a world defined by the fast-paced action of modern technology,” exhibition-wall text reads, “art too must be fundamentally dynamic.” These often-kinetic pieces attempt to convey movement and industry (in the pure sense) through new methods of creating form.

Enrico Castellani’s “Blue Surface 5” introduces a recurring exhibition theme of bulging forms stretching and nearly popping out of canvasses. His “White Surface 2” continues the method. Both works are large canvases dotted underneath with raised nails that give them another dimension.

Giò Pomodoro’s “Opposition” is similar, carefully forming metallic-painted fiberglass so as to appear as though some great machine with varying orifices and points is being born from the artist’s proverbial primordial soup — the same place, one ponders, that these fledgling ideas might have been wrought from.

Le Onde 4

Connoting modern art itself, there is something behind these artworks — literally and otherwise. This is not just a white canvas or a blue one. That is not simply a silvery fiberglass shell. There is something hidden within.

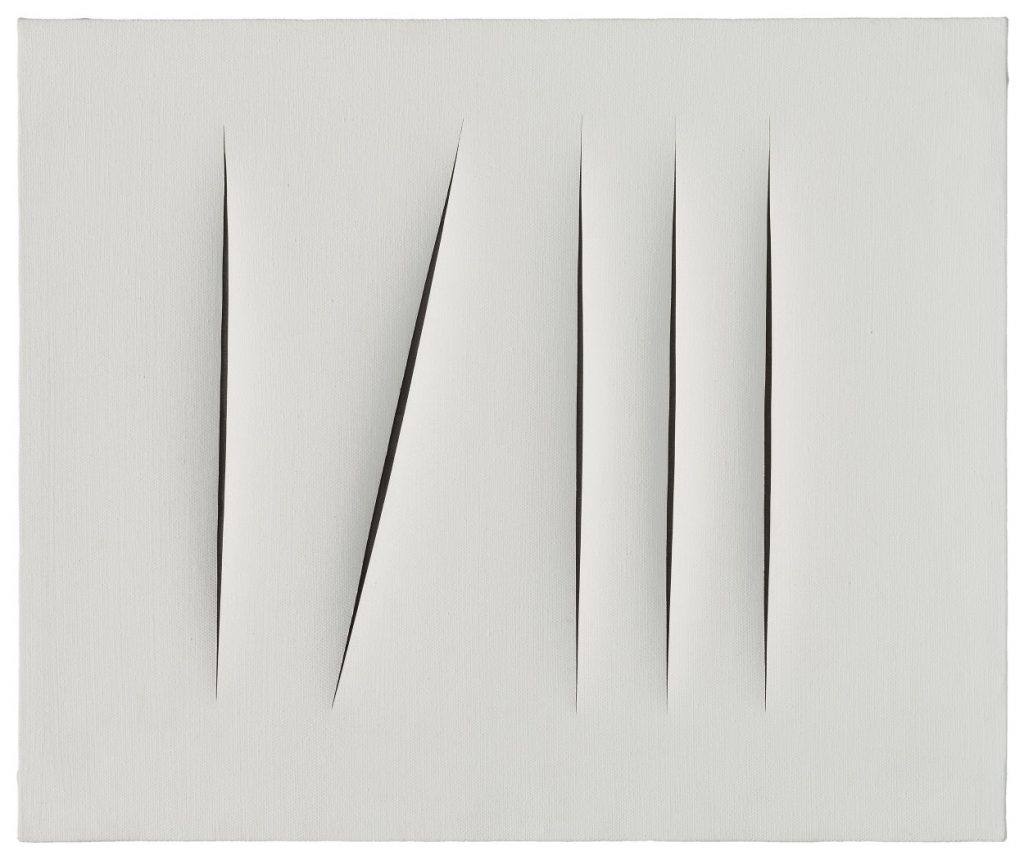

No work (save maybe “Invisible”) hints at this concept more entirely than Lucio Fantana’s “Spatial Concept: Expectations,” which consists of a white canvas slashed five times (four times vertically and once on a diagonal) with practically imperceptible black gauze immediately behind. Aquin said the 1967 work, one of a type that inspired many of the others, was his favorite piece in the show, which opened Aug. 22 and runs through Jan. 3.

Le Onde 2

“These monochromatic canvases that are slit … in such a precise way open up that window of painting onto the real world, which is the void behind it,” Aquin said.

“It’s a gesture of absolute utopia, of wanting to bridge art and life in a very direct and radical way,” he continued. This radical attitude, shared among the entirely avant-garde works on view, hints at how the exhibition’s title (“Le Onde” means “wave” in Italian) is in fact a broader comment on modern art.

“Le Onde also means in Italian the shockwave, the echo, the reverberations,” he said. “It’s not just the wave breaking on the shore, but it’s the influence and the repercussions.

“That’s really what the show is about: the repercussions through time … set forth by the futurists.”

“Le Onde: Waves of Italian Influence” will be at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden until January 2016.

Giovanni Anselmo’s “Invisible” consists of a slide projector beaming the word “Visibile” toward empty space, becoming itself visible when a visitor interacts with it. (Image courtesy of the Hirshhorn Museum)

Lucio Fontana was one of the major champions of spatialism, as evidenced by this white canvas piece slashed to reveal the void below. (Image courtesy of the Hirshhorn Museum)

Giacomo Balla’s “Sculptural Construction of Noise and Speed” (a wall-hanging mass of jumbled, 3-D geometry) is just that: fast and industrial. (Image courtesy of the Hirshhorn Museum)

Giò Pomodoro’s “Opposition” carefully forms metallic-painted fiberglass so as to appear as though some great machine with varying orifices and points. (Image courtesy of the Hirshhorn Museum)