Fukushima will always have a special place in Tsubasa Endoh’s heart.

Though he was born in Tokyo, the Terrapins men’s soccer midfielder spent five years in Fukushima — the capital of the prefecture with the same name in northern Japan — playing for his club team, JFA Academy Fukushima. Endoh lived away from his family during middle school and into high school, but the people of Fukushima welcomed him with open arms.

It became his new home, and the residents of Fukushima were his second family. But at 2:46 p.m. on March 11, 2011, Endoh’s world came crashing down around him — literally.

Endoh was practicing with his team when a 9.0 magnitude earthquake struck 231 miles northeast of Tokyo, spreading catastrophe and chaos throughout the small island nation. He and his teammates were forced to leave their home prefecture — the Japanese equivalent of a state — because of the immense destruction and potential radiation from a nuclear meltdown at the nearby Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

No longer having a place to call its own, the JFA Academy bounced around Japan. Eventually, the group settled in the Shizuoka Prefecture, where they lived and played for a year. But in spring 2012, Endoh said goodbye to his devastated home country and arrived in College Park.

Yet he will never forget the people of Fukushima who accepted him into the community without hesitation when he was young, scared and in a new place, Endoh said last week.

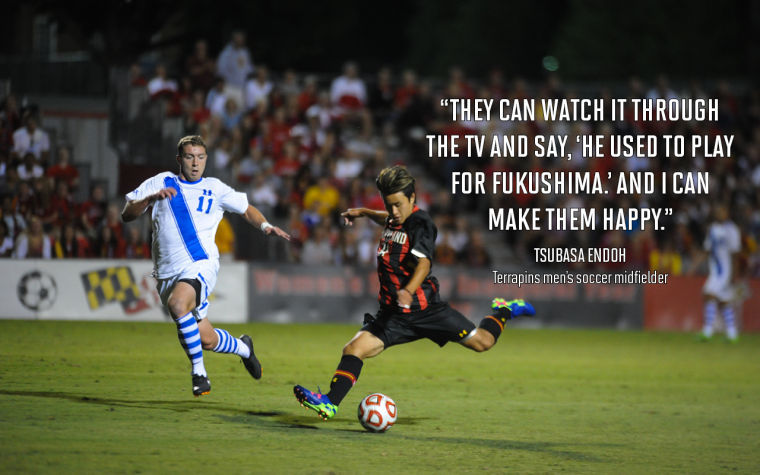

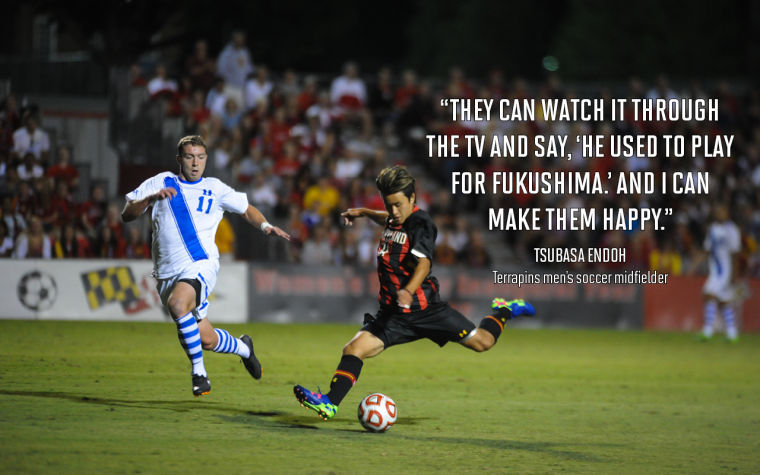

He is now continuing his journey to become a professional soccer player clad in black, yellow, red and white with the Terps, who take on Virginia tonight in Charlottesville, Va. One day, though, he hopes to sport a Japanese national team jersey and provide a glimmer of hope for the thousands of people still struggling with destruction in Fukushima.

“I was appreciated by their people,” Endoh said. “I literally love it over there. Everyone is so kind to us because we play soccer, and we try to contribute to them by playing soccer.”

FATEFUL DAY

It was a typically sunny day in early March, and Endoh was training again with JFA Academy.

The midfielder always enjoyed himself on that soccer field, surrounded by towering light fixtures not unlike those bordering the practice field in College Park. It was a haven, a place where he could escape the stress of daily life, focus his mind and enjoy the company of his teammates.

In an instant, though, his sanctuary became a disaster zone and a typical day became tragic, as the fifth-most powerful earthquake ever recorded slammed the coast.

On the field where he once ran for his love of the game, Endoh now ran to save his life.

“We just got together in the center circle,” Endoh said. “We just sat there.”

(Click to enlarge)

Endoh pull quote 1

The group huddled in an attempt to wait out the massive tremors and then escaped back to their dormitory, which was close to the field. They spent the night inside with no idea of what was occurring outside — light fixtures collapsing, walls crumbling and entire houses collapsing.

The next morning, Endoh and his teammates emerged from safety to find wreckage unlike anything they’d seen before.

“I saw a public road that was destroyed,” Endoh said. “That was crazy.”

The team had no choice but to leave its beloved field — and city — behind. The Daiichi nuclear power plant, about a two-hour drive from Fukushima, was melting down due to equipment failures from the earthquake and the ensuing tsunami, releasing toxic radiation into the air.

It was the first nuclear catastrophe since Russia’s Chernobyl meltdown in 1986 to reach Level 7 — the highest level — on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale, indicating a major disaster.

“With radiation, you can’t see anything,” Endoh said. “It’s an invisible enemy. We can’t do anything about it, so we just tried to escape from that place.”

Endoh and his teammates traveled an hour and a half — in the hectic aftermath, he doesn’t remember where, exactly — to escape the radiation, arriving at a gym that had been converted into a refugee camp for victims. They spent two days there without any food, crowded by the influx of people who had been driven from their homes.

Then the team traveled south to Tokyo, which had not been hit nearly as bad as Japan’s northern prefectures. And while they found refuge in the capital city for a month, Endoh and his teammates were distraught because they didn’t have a field on which to practice.

Without soccer, they felt they were nothing.

“Those were tough times for us,” Endoh said.

Endoh’s family in Tokyo was relatively unaffected by the disaster, but the midfielder remained with JFA Academy throughout the saga. He had an obligation to his team and would not leave his teammates at the time when they needed him most.

The group then moved further south to the Shizuoka prefecture, where it resumed its normal activities. Endoh spent a year there before moving to the United States and joining the Terps.

Since coming to America, though, Endoh has had a tough time remaining in touch with his teammates and acquaintances from JFA Academy and Fukushima. The midfielder has yet to return to Fukushima since the earthquake, and several of his friends are still missing more than two years later.

“I don’t think they are going to find them,” Endoh said.

(Click to enlarge)

Endoh pull quote 2

A THIRD HOME

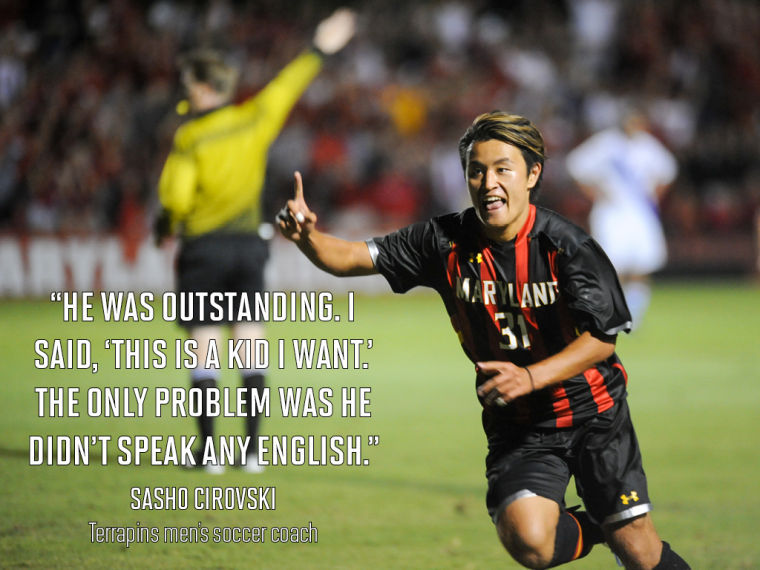

Endoh first caught the eye of coach Sasho Cirovski at a summer camp held at Ludwig Field in summer 2010. Cirovski was refereeing the camp’s all-star game, and he couldn’t help but notice the unassuming Japanese midfielder who was all over the field.

“He was outstanding,” Cirovski said. “I said, ‘This is a kid I want.’ The only problem was he didn’t speak any English.”

Even though he knew he wanted Endoh, Cirovski didn’t pursue the midfielder too hard. It was actually Endoh who reached out to the Terps, expressing significant interest in joining the program.

(Click to enlarge)

Endoh pull quote 4

“He did a lot of work on his own to give himself the chance to come here,” Cirovski said. “I give him a tremendous amount of credit. … We’re reaping the benefits of his commitment.”

Endoh played in 20 games as a freshman in 2012 and finished seventh on the team in points. Midway through the season, the then-freshman’s mother, Hiromi, visited her son in College Park and gave gift bags to every Terps player and coach — a traditional gesture in Japanese culture.

This season, Endoh has burst onto the scene as an integral part of the Terps offense. Though the NCAA cleared him to play just days before the Terps’ season opener, he has started all 11 games and provided an outlet in the middle at attacking midfield, using his speed and constant motor to produce scoring chances for the Terps’ talented forwards.

The midfielder had his best game of the season Sept. 6 in the team’s home opener against Duke, scoring the equalizing goal in the 55th minute and assisting twice in the 3-1 win.

“He brings a love to the game, and you can see it by how hard he works,” forward Patrick Mullins said. “He wants to bring that hard work every day, day in and day out, and it spreads to the rest of the team.”

Unlike most players, though, Endoh has something else driving him. His motivation for becoming a professional soccer player has little to do with personal gain.

Every time Endoh steps on the field, he’s thinking about Fukushima, where the people wasted no time integrating a stranger into their lives. They brought him joy and comfort when he was a middle-schooler away from home for the first time.

(Click to enlarge)

Endoh pull quote 3

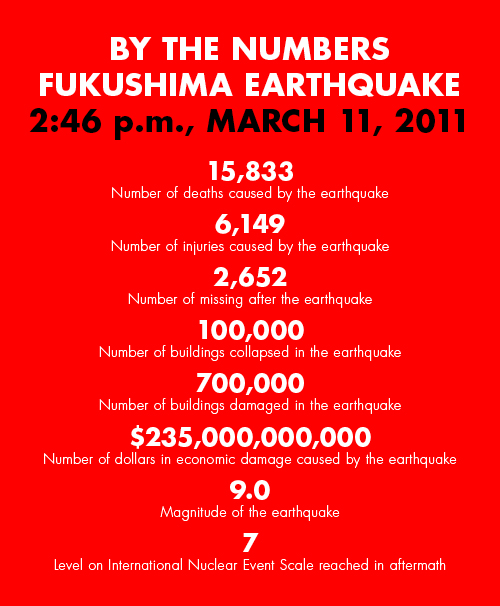

Six months after the earthquake, the Japanese National Police Agency confirmed 15,833 people dead, 6,149 injured and 2,652 missing across 22 prefectures. More than 100,000 buildings collapsed and more than 700,000 were partially damaged. The estimated economic cost totaled $235 billion — the most expensive natural disaster in history.

Endoh will never be able to bring that back, and the Fukushima he once knew and loved will most likely never return.

But maybe one day, all the people who made his life so special for those five years might turn on the television and see a boy from Fukushima representing the shattered prefecture on a national stage.

“They can watch it through the TV and say, ‘He used to play for Fukushima,’” Endoh said. “And I can make them happy.”