Ann Wylie stepped into her office in the geology building and nestled into her old, familiar chair.

She checked her email. Nothing. She checked her voicemail. Nothing. She checked her schedule. Nothing.

It was an unusual and eerie silence for someone who barely sat, barely slept, over the last 15 years.

“The first day I’m here in my office, I didn’t have a single email, a single telephone call or a single meeting,” said Wylie, the former interim provost. “I felt like I’d dropped off the earth.”

On Oct. 1, Wylie stepped down from her year-and-a-half stint in the university’s provost office, where she oversaw the formation of a partnership between this university and the University of Maryland, Baltimore, the hiring of four new deans and a slew of high-level administrators and the creation of the university’s first parental leave policy. But Wylie had to find a way to accomplish all that — and more — in the midst of severe budget cuts, dwindling resources and rising tuition costs.

“The days were busy; sometimes I felt like I never sat down,” she said. “It was fun — I liked the high energy of the job and the diversity of topics that came through. Almost everything that’s a significant issue comes to the provost’s office at some time.”

It’s been four decades since Wylie first began working at the university that’s become her second home. But her job has hardly stayed the same — her posts have ranged from assistant president and chief of staff, to interim dean of the graduate school, to her most recent role as a geology professor.

Her passion for education led her to this university, and it was that same passion that drove her to become involved at all levels of this university, even if they weren’t directly related to teaching. Although she loved working directly with students, she was drawn to administration because of the increased opportunity to work as part of a large team, she said.

On a visit to her native Texas, Wylie said she was dismayed to read a newspaper editorial lambasting higher education, and often worries about the public attitude toward it.

“Nationally, the loss of confidence in higher education as a ticket to prosperity, not only for the country but for the individual, seemed a strange thing to me,” she said. “I’ve always felt I was doing good work and what I did mattered, in different areas and different ways.”

Her colleagues can attest to that. Former university President Dan Mote, who worked with Wylie for seven years, said she was uniquely suited to serve in the administration because of her thorough understanding of the issues and her desire to make the university a better place for students, staff and faculty. She moved through the ranks of the university on the basis of her own merit and determination, Mote added.

“What really made her eyes light up was when she had leadership roles that she could take on herself,” Mote said.

Mote knew that drive would lead Wylie to successfully take on a position as interim dean of the graduate school from 2004 to 2006. And he wasn’t disappointed.

In those two years, Wylie pioneered an effort to award fellowships to doctoral students, who often have trouble finishing their dissertations while simultaneously working other jobs, Mote said. The graduate school was so impressed by her efforts that the fellowships were named after her.

University President Wallace Loh said he saw that same dedication as Wylie served in the university’s No. 2 position while he was still adjusting.

“She’s very thoughtful, but once she reaches a decision, she’s very, very strong and holds fast to it,” he said. “In addition to her strong views and principles, she’s also a team player — a team player who does not shy away from telling you you’re wrong.”

It didn’t matter, because Loh said the two were always able to come to an agreement about the most important issues.

“Sometimes she wins, and sometimes I win,” he said. “Whatever that decision is, we lock arms when we go out.”

Among the wealth of issues Wylie dealt with during her time as provost was the partnership established between this university and the University of Maryland, Baltimore, one of the university’s largest undertakings in recent years. Although there was initially talk of a full merger between the two institutions, Wylie said the resulting pact will allow the schools to move forward more quickly and avoid getting bogged down in the nuts and bolts a merger would have required.

And although discussions and negotiations always take time, Wylie said the ultimate goal was worth the planning and effort.

“People ask me if I was tired of it,” she said. “I found it just exciting to think about planning the future and discussing issues and collaborations that could change the course of the university. … I take pleasure in thinking I had a little bit to do with that.”

But it wasn’t just the massive, groundbreaking projects that made her time in the administration worth it. It was also the victories that directly impacted faculty and staff, such as seeing the university’s first parental leave policy approved this month.

“I never had one day of maternity leave,” she said. “I thought that it was about time that we tried to reflect family-friendly policies.”

Wylie also directly oversaw the hiring of new administrators in Loh’s first months on the campus, including four new deans. Despite what may seem a large turnover, Wylie said the transition was not difficult because the continuity of staff at the lower levels made it easy to adjust to the changes.

“It’s not as overwhelming as it might seem,” she said. “Leadership comes and goes, but the university keeps going on.”

Wylie may have had a tough-love approach, bluntly stating her opinions to get her point across, but that attitude, combined with her knowledge of the university’s history, enabled her to tackle any role, said Donna Wiseman, education school dean.

“She was a straight shooter and could be very abrupt,” Wiseman said. “I could just trust what she said, because she was very consistent and very responsive. … She just loves this campus. She wants this campus to be the best it can be.”

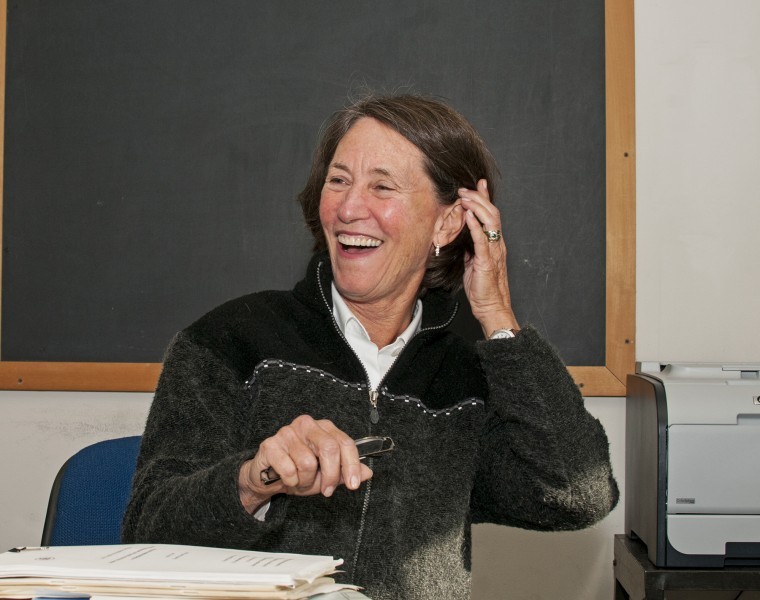

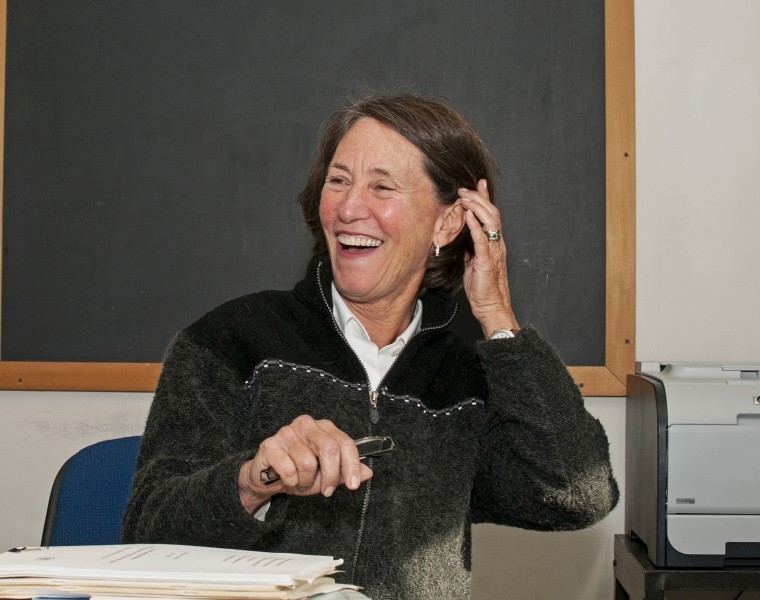

Ann Wylie in her office in the Geology building.

Former interim provost Ann Wylie tears up after receiving a standing ovation at her final University Senate meeting in September. On Oct. 1, she stepped down from the post to return to teaching, after spending a year and a half working to create a partnership with the University of Maryland, Baltimore and hire four new deans, among other accomplishments.