As he entered Byrd Stadium for the 1963 opening football game against N.C. State, player Darryl Hill kept glancing up toward Ellicott Hall, the death threat he received earlier that morning still weighing on his mind.

An anonymous caller warned Hill someone would shoot him from the roof of Ellicott if he stepped out onto the field, which at the time was not protected by the upper deck. So when the Terps celebrated their first points of the game with the traditional cannon firing, Hill dove to the ground, thinking someone had fired a shot at him.

“My teammates — of course, they weren’t aware of what happened — were rolling on the ground, laughing,” Hill said. “I didn’t think it was so funny.”

Fifty years later at Saturday’s homecoming football game, the Terps went up against N.C. State once again, but not before the athletic department took time to honor Hill for paving the way for future generations. As a college athlete, Hill became the first black football player to break the color barrier at this university and in the Atlantic Coast Conference. At Saturday’s game, Hill walked back out onto the field and was presented with a new jersey with the number 50 on the back.

“He blazed the trail for other people to have those opportunities to go to school in the ACC and play football and get a good education,” coach Randy Edsall said of Hill at a news conference last Tuesday.

Athletic Director Kevin Anderson also credited Hill with opening the doors for his own success.

“If it weren’t for pioneers like Darryl, I wouldn’t be sitting here in this room,” Anderson said at the news conference, which was held in Gossett Team House.

However, Hill said during his college football career he was more worried about fumbling the kickoff than being a pioneer.

“But then I started seeing the horrors in the South,” Hill said, adding his best games by far took place in the South, where his mother wasn’t allowed to enter stadiums and his family was booed in the stands. “I got more and more motivated because I thought we needed to shake things up.”

The southern players themselves were decently respectful, Hill said, but the fans were a different story. He remembered his teammates leaving the stadium in a rush without even showering to avoid the threatening crowd surrounding the locker room.

Hill said his teammates always took his side and refused to stay in hotels that prohibited black people. The president of the university at the time, Wilson Elkins, also fought to keep Hill on the team when the Board of Trustees said he couldn’t put a black football player on the field.

“He told them, ‘That’s not your call — it’s mine. You see me next year at contract negotiations,’” Hill said.

Within a decade, things had changed dramatically — black football players started for southern teams such as Clemson, where Hill’s own family was barred from the stadium during his football career.

“I think sports is the single most important factor to social togetherness that this nation has ever known,” Hill said. “When blacks began to play college sports, that changed the whole landscape.”

Hill’s story also inspired English professor Michael Olmert to write a play, Moving the Chains, which had a staged reading at the Lincoln Theatre in Washington in March 2011. The script recently evolved into a screenplay, Illegal Contact, and production of the film is expected to begin late this year or early next year.

“[Hill] just electrified the team,” said Olmert, who graduated from this university the year Hill enrolled. “He had good hands, and he was fast. And everybody loved him. He had a great personality.”

Today, Hill recognizes the impact he had on college football and seeks to fight against economic discrimination in youth sports with his foundation, Kids Can Play USA. The foundation helps low-income families meet the costs of league fees and charges and pay for equipment.

“The idea is to remove the economic barriers from sports so that all American children can play. The youth sports now come with a price, and less fortunate children are being left out,” Hill said. “Our vision is a return to the day where sports are free and open to all children.”

While Hill continues to enjoy watching the Terps play, the sound of the cannon still makes him jump.

“Some things you never forget,” Hill said. “That cannon was one of them.”

Alumnus Darryl Hill, who was the first-ever black football player at this university and in the ACC, was honored at Saturday’s homecoming football game. On the field, he was presented with a new jersey with the number 50.

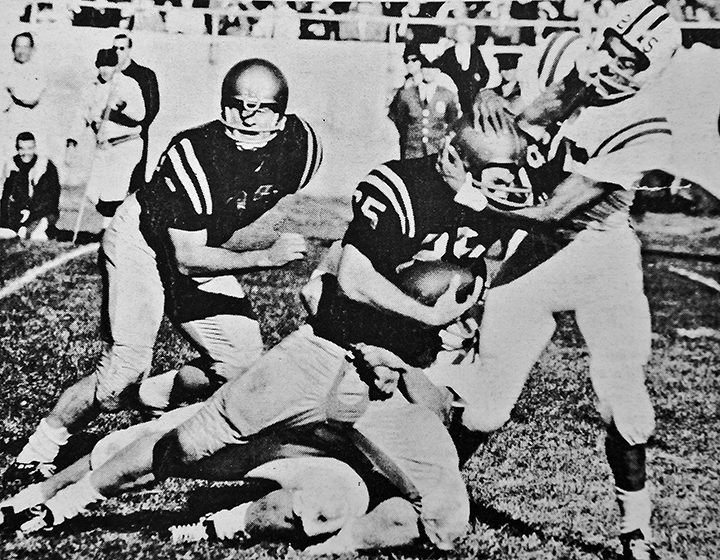

Darryl Hill (far right) helped integrate Terps and ACC football in 1962 after transferring from the U.S. Naval Academy. The university honored Hill at Saturday’s homecoming game against N.C. State, marking 50 years since breaking the conference’s color barrier.