A robotic fish in the Biology-Psychology Building could give university researchers, led by aerospace engineering professor Derek Paley, insight into autonomous underwater exploration.

Of the scores of fish kept in a small laboratory on the second floor of the Biology-Psychology Building, one sticks out from the rest.

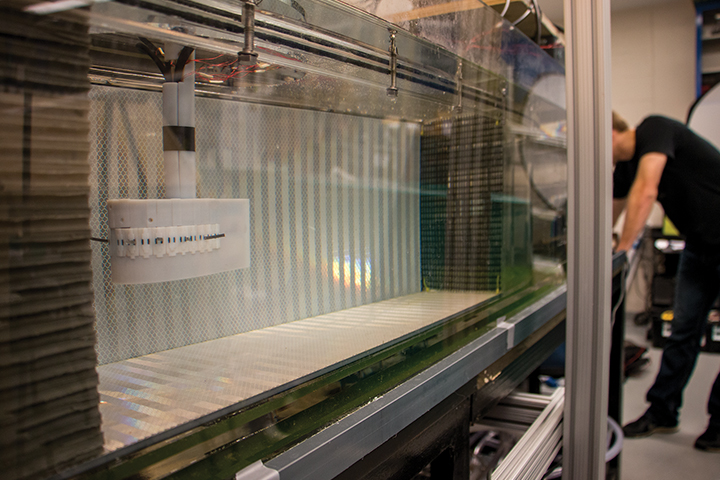

Its body is white and it sometimes swims in a tank along the lab’s back wall. Under the right circumstances, it will act like the other fish. But it has no eyes or gills, and a metal apparatus hangs above it.

This fish isn’t really a fish. It’s a robot.

University researchers, led by aerospace engineering professor Derek Paley, have been designing and programming the robot since 2011 in collaboration with scientists from Michigan State University and Bowling Green State University. While the robot’s functions are basic, the research behind it could significantly impact future autonomous underwater exploration.

“It makes sense,” said Frank Lagor, a second-year aerospace engineering doctoral candidate and one of the project’s primary researchers at this university. “Fish are autonomous creatures. Why don’t we have our autonomous vehicles do things the way the fish do? It’s a bio-inspired approach.”

The robotic fish does two things on its own that other fish do instinctively: It adjusts to face the current head-on, an act called rheotaxis, and it moves behind objects blocking the direct current to conserve energy, which is called station-holding.

These behaviors are based on algorithms the researchers wrote for the robotic fish.

“We hit ‘go,’ and then we step away,” Lagor said. “The fish makes his own decisions.”

But they have only tested the robot in controlled conditions. The next step is to move the experiment from the lab to the real world, said Levi DeVries, a fourth-year aerospace engineering doctoral candidate and fellow primary researcher at this university.

“We’re hoping to take this thing into an outdoor river somewhere around here in the next month or two and test these same algorithms in a kind of natural environment,” he said.

According to Lagor, the experiment, which will be set up in a do-it-yourself fashion, will be an incremental step that could build up to more complex problems.

“For that test, we’re really not looking to do anything more sophisticated than take this setup and put it in the river and see how it does,” he said. “We’re literally going to put cinder blocks on the ground and put the system on top.”

The team will have to secure additional funds to continue its research, Lagor said. It’s in the last phase of a three-year, $625,000 grant from the Office of Naval Research. Paley, the principal investigator, has been drafting grant proposals to continue the team’s research.

When research began in 2011, everything was practiced in theory, DeVries said. It wasn’t until Lagor — who has both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in material sciences and worked as a mechanical engineer for Lockheed Martin for several years — came to the project with his mechanical expertise that the team began physical experimentation.

“We didn’t have any of this equipment here, so it was all done in simulations on computers,” DeVries said.

Lagor designed the tank and set up much of the equipment, which cost about $40,000, the researchers said. Once it was constructed, Lagor and DeVries merged experimentation — Lagor’s specialty — with theory, which is DeVries’.

If everything goes according to plan, researchers hope to design a robot that looks and moves more like a fish. A possible prototype would include natural propulsion and a flexible body.

“Right now, that’s not our focus,” DeVries said. “We’re more interested in the basic science than the hardware that you might need.”