By the numbers

Despite presidential increases in both the number of Pell grant recipients and the maximum award amount, experts said rapidly rising college costs overshadow the program’s expansion.

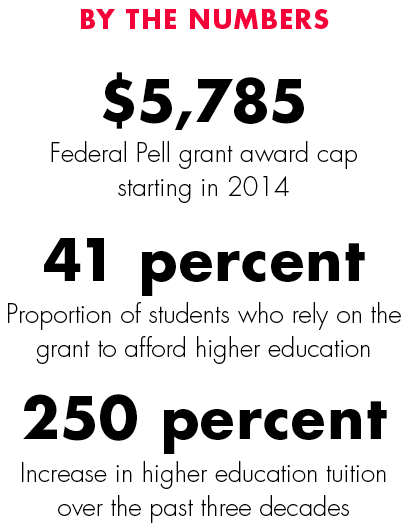

The maximum amount students will be able to receive from the need-based college grant program in 2014 is $5,785, an increase of $140 over this year. About 41 percent of students rely on the grant, but with the rise in tuition, next year’s Pell grant may cover less than one-third the average cost of a four-year public college, according to The Institute for College Access & Success.

“It’s clearly time for policymakers to stop asking whether Pell Grants are sustainable and focus instead on whether they’re sufficient,” TICAS said in a statement on its website last week.

In the 1980s, the maximum grants could cover about half the cost of

tuition at a public four-year school, according to TICAS. But burgeoning tuition and other fees — up 250 percent over the past three decades — far outpaces the growth of the program and increases in family income.

“Although Pell grants had increased markedly in its size and its reach, it’s been hindered in its impact by the growth in tuition and fees,” said Michael Dannenberg, director of higher education and education finance policy at The Education Trust.

The discrepancy between college costs and Pell grant awards is made even worse because recipients are twice as likely as other students to take out student loans, according to TICAS.

University Financial Aid Director Sarah Bauder said it’s important not just to look at the dollar amount but also at the policy surrounding the program. The main objective of Pell grants, Bauder said, is to financially “level the playing field for disadvantaged students.

“I would give it maybe a ‘D’ plus,” Bauder added.

Changes to the program in 2011 remain a hindrance to college access and completion for students who don’t take the traditional four- to six-year path to graduation, Bauder said.

One provision decreased the number of semesters recipients can claim such grants from 18 to 12, putting students at a disadvantage, she said. Almost half of black students and 40 percent of Hispanic students use the federal program, according to TICAS.

“We get a lot of transfer students who are already at the six-year level,” Bauder said.

“They dropped out, came back, dropped out, came back for whatever reason … and they’re not eligible.”

Other provisions in 2011 also lowered the threshold for students with financial needs to claim the maximum Pell grant awards. Now families at or below an income level of $23,000 can claim the maximum grant, compared to the previously projected income threshold of $32,000.

“I think $23,000 is an extremely low threshold for poverty,” Bauder said.

On the policy front, lawmakers have been absorbed with debates over student loan interest rates, Bauder said, while the dialogue on improving outcomes with Pell grant money has been drowned out.

“There are two sides to the college affordability ledger,” Dannenberg said. The overall price of tuition alongside a family’s ability to pay both out-of-pocket and with financial aid, should be considered, he said, adding that policymakers tend only to focus on one aspect of the issue.

An important part of closing the gap between financial aid and college costs is getting a “dysfunctional marketplace” under control, Dannenberg said.

“Supply is relatively finite, and demand is high, uninformed and at times, irrational,” he said.

The best policy option to solving the “college affordability conundrum,” Dannenberg said, would be to better prepare students in high school for the oncoming burden of college costs. Additionally, he said, legislators should work toward reform that would help students graduate in four years — instead of the average five-year graduation rate — to bring down costs.