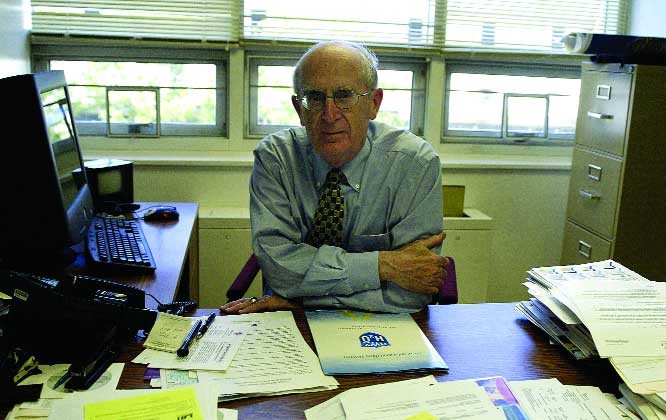

University Professor Gerald Galloway headed a Clinton-era task force that studied how to prevent devastating damage by floods in Mississippi and Louisiana.

Flooding following Hurricane Katrina has devastated and displaced thousands of residents of Mississippi and Louisiana. The federal government is working to provide victims with much-needed food, water and health care.

And experts are clamoring to find out what went wrong.

Following the Great Flood of ’93 that caused more than $15 billion worth of damage, university professor Dr. Gerald Galloway, an expert on flood protection, was asked by President Clinton to head a task force on the causes of the devastation. The task force authored a government report, titled “The Galloway Report,” recommending ways to minimize destruction from flooding in the future.

Galloway said damage in New Orleans would have been significantly reduced if his recommendations had been followed. He agreed to be interviewed by a Diamondback reporter about the report, how it applies to Hurricane Katrina and how people can be better prepared in the future.

Q: What was the purpose of the task force you led?

A: President Clinton wanted to know why we had a big flood when the Mississippi had some people underwater for six months. He wanted to know what are the rules and procedures that say why we do what we do in the federal government and what should be changed. It’s an amazing thing — we were together for six months. For the next year, we worked part time answering questions about it.

Q: What did you discover about the cause of the ’93 flood?

A: We discovered that the ’93 flood was a significant hydrometeorological event. Now what does that mean? I went and I told Vice President Gore. He said, “Why did this flood occur? Is it because we built levees too close, because we did this or that?” I said, “There was a significant hydrometeorological event.” He said, “What does that mean?” I said, “It rained a lot.” It saturated the ground. It filled the little creeks. It filled the little rivers. It filled the big rivers. And then when there was no where else to go, it went up, on the properties. And the second, equally significant thing was big floods are natural and will continue to occur. The other part of that, because it’s relevant to Katrina, is that if people don’t need to be in a floodplain, where the river is going to rise, they should develop somewhere else. If they have been damaged several times, they ought to move out of the flood plain, unless there is a reason, historic or otherwise, why they should be there. We specifically talked about New Orleans and Sacramento and cities that live and work around a river and a port, then they’re obviously a different case. Then we’ve got to protect them so we don’t have other big floods like the Mississippi flood.

Q: What kinds of recommendations did you make to the administration, based on your findings?

A: Well, we said that there ought to be a floodplain management act that defines the responsibilities across all levels of government. We said that you have to make sure that people in the floodplain buy insurance because the penetration rate is something like 10 to 30 percent. Even though you’re more likely, if you live in a floodplain, to have a flood than a fire, everybody has fire insurance. We said also that organizations should discourage people from living where they’re going to be flooded. Don’t develop in floodplains if you can develop somewhere else. Then we said, in the case of people that live behind a levee … they should have insurance, because the day is going to come when that levee overtops, and then the federal government shouldn’t pay, that ought to be something they pay for in their insurance.

Q: How much of the task force’s recommendations were heeded by the Clinton administration?

A: They came awfully close a couple of times to doing some really neat things, but did not. Probably, 30 to 40 percent of the recommendations. We had a long list of recommendations, some of they did partially, some of them they didn’t do at all, some of them fell in the “too hard” box. What they did was, try and do those things they could get to easily, and work on some others. President Clinton, almost, on his last day in office, signed an executive order, but it fell to low on the priorities. There’s a wonderful statement I would make to you that says, the half-life of the memory of a flood is very short. People forget about the flood. Your house can be underwater, you come back, you fix it up in a year, [you say,] “Why worry about that? Why buy the insurance? It’ll never happen again.” And the politicians especially, have a very short memory.

Q: Why do you think most of the recommendations weren’t taken into account?

A: It’s awfully hard to tell somebody to do something they don’t want to do. So faced with tough love, most people don’t give tough love. One of the recommendations we had was that levees around metropolitan areas should be at a certain level called the standard project level because that’s a reasonable amount with protection; New Orleans has that on the Mississippi River, [but] didn’t have it on the lakeside. And we ought to have that as a national standard. Well, the budgeteers say, “We can’t afford that.” And so, they push that aside. Those are the sorts of challenges. We are in a budget-constrained environment. What that means is, if you don’t have enough money, you have to give up something you don’t want to give up. And if nobody’s clamoring for this, then you have a problem. If people aren’t beating down your doorway saying “do this” or “do that,” you have a problem.

Q: Do you think that if the recommendations had been heeded more, a large portion of the disaster related to Katrina might have been averted?

A: I don’t want to say everything would have been different. People would have had insurance, which they don’t have, that’s one thing. So there would be less of a burden on the nation and on them. Second, there might have been more incentive to give engineers to make the levee higher. [It’s questionable] whether any one act would have prevented this because it takes 20 years to build a structure like that. I think the issue is, my goodness, we need to do something about this now! We didn’t do it 10 years ago, let’s go back and look at this and see what we need to do.

Q: In light of Katrina, what do you think should be done in the future?

A: Katrina is a wake-up call to the nation to look up and see who else is protected by a levee. Who else has flood protection that may not be at the level of protection they would like to have? Again, the engineers of the state of California say, “We really think the levee ought to be a 200-year levee.” Yet all the city of Sacramento wants, or so far has been willing to pay for, is a 100-year levee. There’s a one in four chance, statistically, that that 100-year levee will be overtopped within the length of a 30-year mortgage; 26 percent chance that it will be exceeded within any 30-year period. Now would you want to live in a place, the capital of the eighth largest economy in the world, California, would you like to live there with a levee that only provides just enough protection? And there are more than 20 other cities in the country like that.

Q: Do you think that the federal government will learn from this experience?

A: I listened to the president today on television, and he said, “We are really going to learn from this. I’m going to find out what went right and what went wrong, and we’re going to change it.” And I believe him. I think that, again, our plans from Friday on have worked beautifully. When the military forces came in there and you saw those helicopters and you saw that general in New Orleans, and you saw the state and other organizations working together, it’s magnificent. But the two issues are the immediate response issue and the pre-disaster issue. Those issues have to be looked at very carefully. Everybody agrees to that. And so I think they will certainly make some steps. Now the president said, and I agree with him, we have to be prepared for natural disasters and terrorism, and we need to know what happens when you have something like this. I think they had lots of plans in [the Department of Homeland Security] as to how to deal with big events. Now we have a chance to exercise it. We’re going to shake out the big problems, and I think we’ll go into the next disaster much better prepared.

Q: Is there anything people can do to protect themselves from such a disaster?

A: If I lived in New Orleans and I was going back to build my house, first of all, I’d hope that the mayor and the city council would say if you rebuild your house, here’s what you have to do to make it more flood-proof. You might build the first floor elevation up a little higher, you might ensure that the fuse-boxes are on the second floor, start off the assumption that someday you might have a flood, so you protect your investment that way. I think that’s what we really need to do. No one’s saying, “Don’t go back to New Orleans.” But make sure we don’t put people in the deepest holes. That’s the least valuable land. Find some way to give poor people a better break.

Contact reporter Megha Rajagopalan at rajagopalandbk@gmail.com.