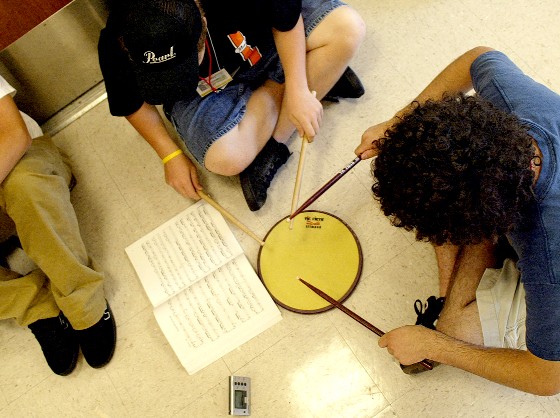

Participants in the UM percussion ensemble workshop wait in the hallway of CSPAC for a clinic with Chris Deviney.

It was only 8:30 on Tuesday morning, but the band room in the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center jived with the rhythm of Carlos Santana’s “Primavera.”

Jived too enthusiastically, percussionist John Kilkenny told the assembled high school students, as he scolded them for a common amateur’s mistake: rushing the tempo of the beat as the sound volume swelled.

Forty-two high school students from across the country have descended upon the campus this week to study with a veritable “Who’s-Who” of the American professional percussion community, assembled by John Tafoya, School of Music professor and a principal timpanist of the National Symphony Orchestra.

They will help the students perfect marimba, timpani and snare drum techniques during a series of workshops. The experience was also designed to help guide the students in possible careers in an insular field known to be highly competitive and often underpaid.

A handful of university music majors focused in percussion volunteered to remain on the campus to serve as resident assistants — herding the younger students back to their South Campus quarters at the end of the day, wheeling the kitchen table-sized marimbas between practice rooms — and to establish as many connections as possible with the professionals leading the workshops.

Ashley Baier, a rising junior music major, aspires to be a studio percussionist at a time when digitally produced rhythms fill an increasing number of albums and soundtracks.

Andrew Kreysa, a rising fifth-year music major, just wants to be “a solo marimbist who can support [his] family.”

Baier was especially excited to meet Shawn Pelton, drummer for the band on Saturday Night Live, and Tim Adams, an instructor at Carnegie Mellon University and principal timpanist for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. His snare drum solo Monday evening at the workshop’s opening concert left many of the high school students bobbing their heads, eyes closed in appreciation.

Kreysa anticipated a private lesson with Nancy Zeltsman of the Boston Conservatory and clinics with Chris Deviney of the Houston Symphony Orchestra.

“You’re going to get hired because of who you studied with,” Baier said.

Tafoya, who became percussion faculty director in 1999, remembers when the music school was crammed into the Tawes Fine Arts Building with limited rehearsal and performance space.

“We wouldn’t even dream of doing [a similar workshop there],” he said.

When he toured the brand new CSPAC in 2001, he said, “my first thought was all the things we could do here — all the programs we could offer.”

The same windfall from the state and private donors that allowed the university to build the $130 million center left the percussion department with $450,000 for new instruments and equipment — an impressive sum that surprised Tafoya, he said.

“I said, ‘Let’s get one of everything that’s out there,’” Tafoya said, recalling he was excited to earmark the funds for instruments before the university could adjust the budget.

The department spent $150,000 alone on timpanis; because certain brands of the large drums are handmade, the department only finished outfitting itself last year.

“Students need to play on professional-grade instruments so they get the sounds professionals expect to hear,” Tafoya said.

He said it was not difficult to assemble the instruction roster because he has studied or performed with almost every percussionist at the workshop and agreed with Kilkenny there are about three degrees of separation between every professional.

“The best thing they’re doing this week is exposing [the students] to different styles of music,” said Kilkenny, who performs with an ensemble Kreysa described as one of the best-known in North America. He also helped organize the workshop. “Hopefully, some of it will stick, and they’ll want to know about the composers.”

The close connection between musicians begins in school, said Kreysa and Baier, describing movie nights at other students’ apartments and evenings with Tafoya at Hard Times Cafe after concerts. This fall, there will be 18 percussion students, an increase from the six Kreysa remembers from his freshman year when the department struggled to cover all the parts in ensemble rehearsals.

“Whenever there’s a party or I’m just hanging out, I’ll call all the percussionists, and if they can’t come I think, ‘Well, maybe I’ll call my other friends,’” Kreysa said.

Employment after graduation is a worry for even the younger students in a business in which moving to a new city means a few steps back career-wise and graduates face stretches of sporadic, low-paying or even free gigs to establish their reputations.

“You have to check your e-mail constantly because if someone asks you to do a gig and you don’t get back to them in six hours, they’ll ask somebody else,” Kreysa said.

Baier said that a part with a major city’s symphony orchestra is considered one of the most prestigious jobs, and the United States Marine Band is a traditional attraction for talented young musicians.

“But if you get a job playing drums for Ashlee Simpson, that’s good too,” she added, over dinner Tuesday night.

Kreysa shot her a disdainful glance.

“I’d rather have an aneurysm than play drums for Ashlee Simpson,” he said.