Kendrick Lamar comes from a long line of Compton rappers who document their city’s woes.

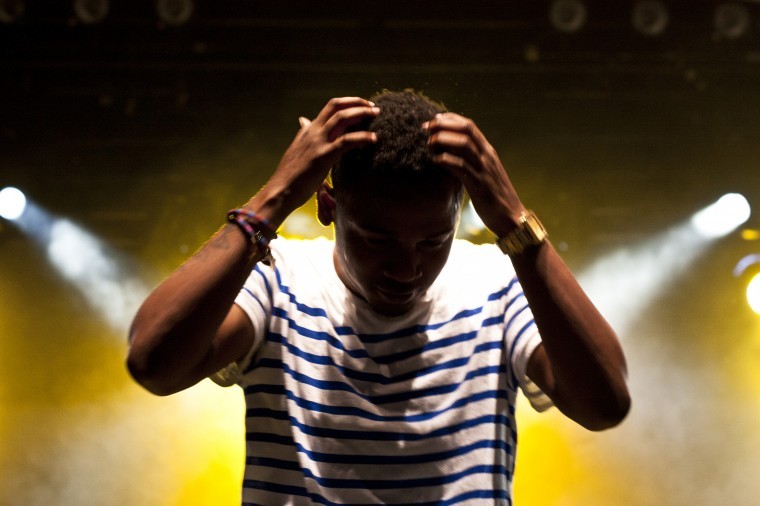

Expectations are daunting. They can work to either crumble a career or push it to stardom. Kendrick Lamar’s Section .80, released last year, received widespread critical acclaim, with some even hailing him as the second coming of Tupac Shakur. Suddenly, this 20-something from Compton, Calif., with a nasal delivery was being mentored by Dr. Dre and credited with saving hip-hop from the dark depths of the pop-music scene.

It’s safe to say with the release of good kid, m.A.A.d city, Lamar’s major-label debut, the young rapper has met, if not exceeded, expectations. In today’s music industry, with its obsessive focus on singles and radio play, it’s hard to release a cohesive, stand-alone rap album. Lamar has created a record so perfectly constructed, it becomes an almost cinematic experience, in the vein of Kanye West’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.

Lamar sacrifices catchy choruses for intricate, detail-driven verses. He skips out on feature MCs, instead opting for verses from fellow rappers that fit the tone of each individual song. He forgoes total accessibility for the sake of complete storytelling.

Good kid, m.A.A.d city is filled with risks most hip-hop artists today wouldn’t dare take. Lamar twists his vocal delivery on nearly every track, ranging from a robotic sing-song tone on “Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe,” to the jittery anxiety that pervades his flow on the superb “m.A.A.d city.” Each track is handcrafted, from the beat to the tone of voice, so the story Lamar is telling comes off with an authenticity and a level of sincerity absent on the majority of contemporary hip-hop albums.

The album’s true strength lies in its storytelling. From beginning to end, Lamar recreates a day in his life growing up in Compton. Starting with the track “Sherane a.k.a Master Splinter’s Daughter,” we get an introduction to the love of Lamar’s life: a girl he knows he has no business hanging around. Employing an eerie, prayer-like intro, a deep, bass-driven beat and ending with a voice mail from his mom, the entire song is packed with the emotional gut punches that make the album so engaging.

The story continues, unfolding as a nonlinear, abstract tale detailing the various aspects of Compton life that made living seem more like surviving. “Backseat Freestyle” packs a sonically astounding trap-rap beat with lyrics that seem shallow at first glance, but reveal a deeper brilliance on second listen. Kendrick grew up in a society in which you had to be bad in order to impress; there was no room for individual expression. You either followed in line with the “Compton way” or were ridiculed. When Lamar explains, spitting out, “All my life I want money and power/ Respect my mind or die from lead showers,” you start to feel sympathy for this character trapped in such a one-dimensional world. He’s hanging with his friends, bumming around Compton and he can’t seem to break free and live the kind of life he wants to.

This sense of entrapment is expertly reflected in one of the album’s best cuts, “The Art of Peer Pressure.” The track shifts sounds and textures constantly, from an old-school beat and vocally manipulated intro to the dark, almost malicious verses that take up the majority of the track. One line, however, seems to sum up Lamar’s overbearing struggle to conform to the life he seems to have been born into: “I got the blunt in my mouth, usually I’m drug-free/ But shit, I’m with the homies.”

Compton has supplied hip-hop with some of the most socially conscious rappers in the game. Lamar is no different. He may not become the face of hip-hop, but he should be respected, revered and certainly commended. His album is a masterpiece that tells a story most rap records avoid for fear of confrontation or lack of acceptance. Lamar is self-assured in both his knack for situational lyricism and superb beats, a couple of traits that should solidify his place in the upper echelon of rap artists for years to come.

diversionsdbk@gmail.com