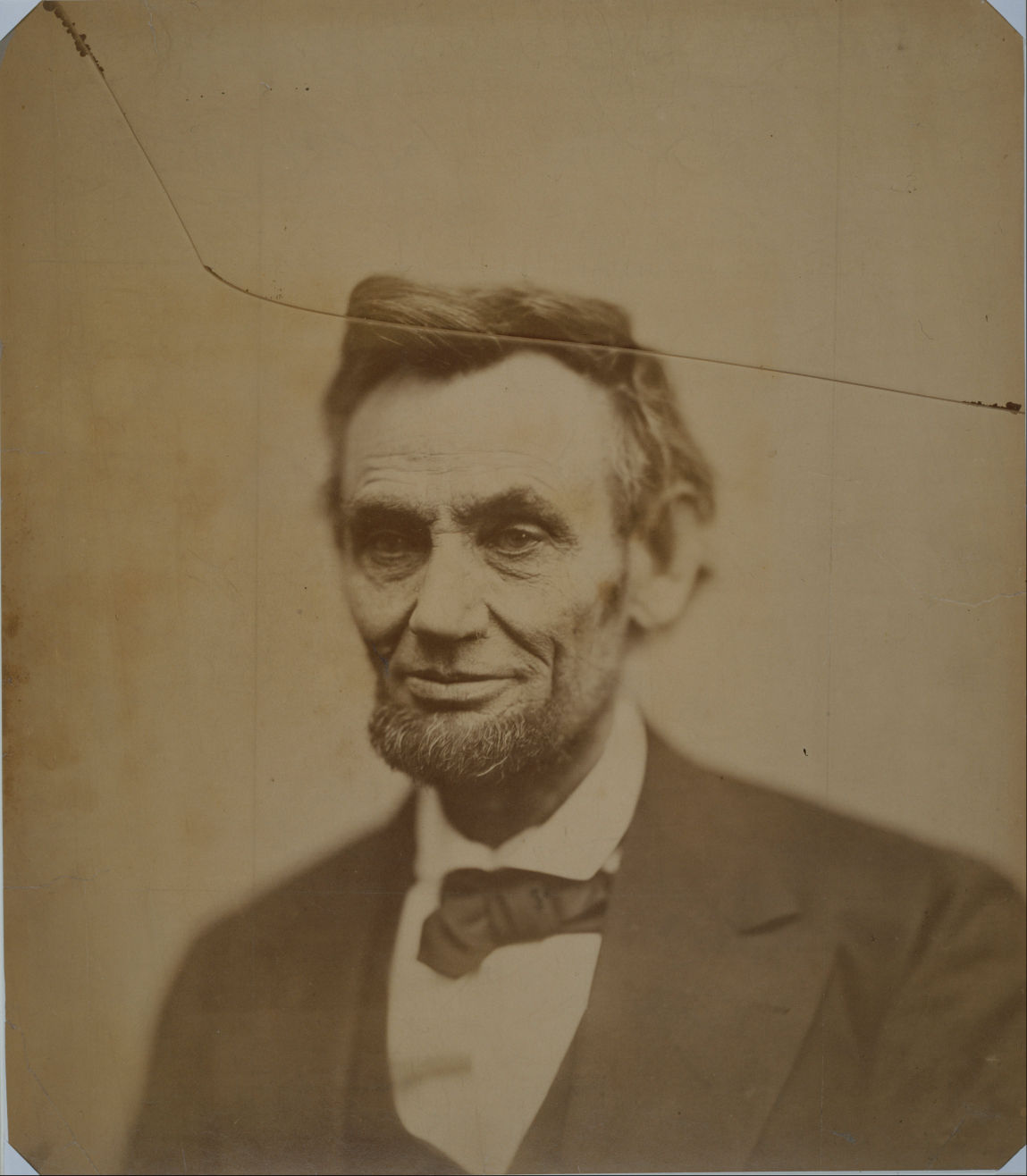

In a news release for the National Portrait Gallery’s new Alexander Gardner exhibition, director Kim Sajet calls the civil war photographer’s cracked-plate portrait of Abraham Lincoln the museum’s Mona Lisa.

Gardner took the photo just two months before Lincoln’s assassination. When the negative’s glass plate fractured during development, Gardner simply threw it away, having made just one print, fuzzy and marred by the dark crack. He likely thought nothing more of it.

Little did he know the solitary copy of the botched portrait (seen for real in the NPG in place of the replica the gallery usually hangs) would become so important.

“We read back into the past what we know will happen, but that Lincoln didn’t,” NPG Senior Historian David Ward said at a press preview. The fuzziness and striking break reinforce our nation’s brokenness and confusion throughout the Civil War era and after Lincoln’s death.

“This is Lincoln on the cross,” Ward said. “The pivotal moment of what was and what was to be.”

That undercurrent of past intersecting drastically with present is a strong force in the enormous exhibition, which will open Friday.

While the 140-plus-piece show is undoubtedly the NPG’s marquee event of the year, Sajet stressed the exhibition’s grave context.

“We have to be careful,” she said at the preview. “We’re not jubilant about this exhibition; this is not in any way a celebration. There’s a great deal of sorrow in this exhibition.”

“Gardner was deeply sorrowful … and in the impact of the pictures it shines through: that innate sadness on behalf of what man has done to man,” Sajet said. “I think Gardner, perhaps more than any other American artist in the mid-19th century, was at the center of … profound cultural change.”

Ward elaborated on one such transformative moment. Early in the exhibition is a photograph of the Marshall House, an Alexandria establishment from which the secessionist owner hung a large Confederate flag about a month after Fort Sumter. When Union Col. Elmer Ellsworth took down the flag, the owner, James Jackson, killed Ellsworth before being shot and killed by Union Cpl. Francis Brownell, according to a 2013 report by WTOP.

Ellsworth’s body lay for public viewing at the White House, Ward said, and many thought he might be one of few casualties of the crisis.

“The notion that you could have an individual soldier lie in state like a medieval knight is certainly ironic, if not actually sort of tragic, showing the naivete of the war,” Ward said.

Weeks later, the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single day of battle on American soil, would dispel any remaining innocence. Thursday is the 153rd anniversary of that battle, which ended with 23,000 casualties and began a new era in American warfare.

“[Gardner] took his camera to the battlefield two days afterwards, and it was when the dead were still lying around,” Sajet said. “It was the first time that … the press really understood the cost of war.”

Added Ward: “This was the moment in American history. We were never as innocent as we thought we were, but the Civil War killed any possibility that we would be innocent thereafter. This was where America enters the modern world.”

One of the exhibition’s best features is a replica of a stereoscope, a device that superimposes two nearly-identical images to create a rudimentary 3-D effect. In the Antietam images of ditch-strewn bodies, singed scrub brush and idle artillery wagons, the battle itself seems as if it has just finished — the quiet after the storm, so to speak. The 3-D effect brings them to life, as if in the present. They are chilling.

Gardner found extreme success with these gory, gothic images of death at Antietam and attempted to repeat his success after the Battle of Gettysburg.

Instead, it was on that bloody field in Pennsylvania that Gardner found infamy. No Gardner retrospective would be complete without the harrowing photographs he made there, but no review of that exhibition would be complete without discussing the immoral way he made them.

According to Ward, forensic analysis confirms Gardner exhumed, moved, posed and misrepresented a Confederate corpse to create Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter and Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep, both on view. In another work, Gardner removed corpses’ shoes, turned out their pockets to simulate looting and misstated the corpses’ locations in order to create notoriety.

“At the very dawn of photography, the question is: ‘Can you trust photography?’” Ward said. He stopped short of justifying Gardner’s actions, but explained the photographer was trying to make the war more familiar to viewers through narrative.

Carl Stepp, a journalism professor at this university, agreed. “I think their thought was probably: ‘How can we use what we have in front of us to create the best possible message?’” he said. “They were providing what, in the 1860s, was documentary evidence of what was going on the world.”

“You know, print journalists were not above exaggeration,” Stepp added, chuckling.

Ward believes Lincoln backed Gardner’s message strongly. Gardner was Lincoln’s favorite photographer, and in sitting for an 1863 portrait, the president likely saw Gardner’s images from Gettysburg. Ward believes these tableaux influenced how Lincoln approached his Gettysburg Address just weeks later.

Gardner’s bond with Lincoln continued through the second inauguration and eventually to the cracked-plate portrait. In Gardner’s photograph of the inauguration, John Wilkes Booth is visible in the crowd. It’s a solemn reminder that these two figures, divided hugely as assassin and victim, as Unionist and Confederate, as exalted and shunned, were two surprisingly close characters in the play of history.

The exhibition bridges so many of these divides: between Northern and Southern geography, between Victorian sensibilities and modern realities, between life and death on the battlefield, and between truth and fiction in documentary.

The past and present collide in Washington, D.C., where so much of American history has been decided. The Capitol Dome, under construction in the first inauguration’s photos, floats blocks away, once more draped in scaffolding.

The Old Patent Office Building — the architect of which Gardner photographed and which was, for three years, a Civil War hospital — now houses the Portrait Gallery, including this expansive, immersive exhibition.

Coming when it does, just more than 150 years since the war and on the edge of a new sectional crisis in American race and party politics, the exhibition demands we take stock of our surprisingly recent failings.

It might seem far away when Booth yelled “sic semper tyrannis” (“thus always to tyrants”) from the stage at Ford’s Theater or when national controversy erupted after the removal of a Confederate flag.

But “sic semper tyrannis” still adorns the flag of Virginia, and in many Southern cities the Stars and Bars still fly.

Will this house divided ever truly stand? We don’t know, but hopefully someone’s there to take a picture.

“Alexander Gardner: Dark Fields of the Republic” closes March 13, 2016. The National Portrait Gallery is at the Gallery Place/Chinatown Metro station.