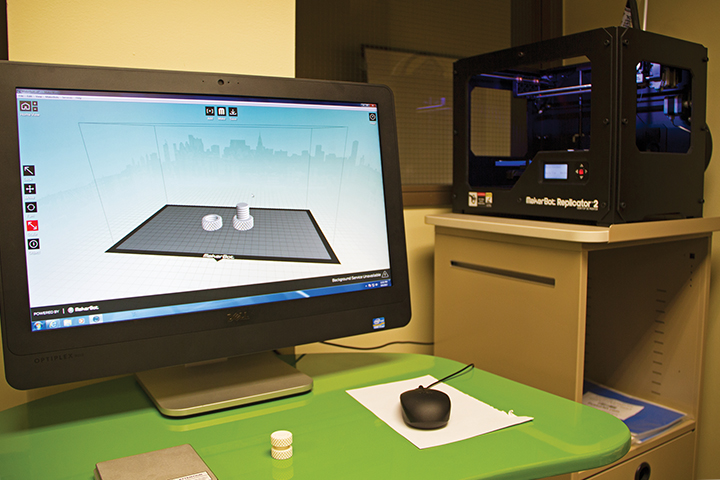

McKeldin Library now has the capability to print 3-dimensional objects on the second floor with the new MakerBot Replicator.

There’s a brand new 3-D printer in McKeldin Library, and anyone can use it. But so far, no one has.

Nestled in a corner behind the Terrapin Learning Commons Tech Desk on the library’s second floor, the microwave-sized, black-accented MakerBot Replicator 2 glows blue through a window. The $2,500 piece of equipment, paid for through funds from the student technology fee, officially became accessible to the public on Friday, and learning commons staff said they are still waiting for the first person to request to print an object.

“We wanted to give students across different disciplines access to a resource they may not have through their own department,” said Gary White, library public services associate dean. “A low-cost way to bring an idea of innovation forward.”

The learning commons staff is on hand to acquaint students with the MakerBot, a machine that uses specialized software to design and print 3-D objects made of soft, moldable plastic. With printing

by weight coming to 20 cents per gram, a small nut and bolt might cost 80 cents, while a Terrapin figurine the size of a hand would be about $20, according to learning commons coordinator Kevin Hammett.

The staff is counting on students to come up with creative uses for the printer, Hammett said.

“It’s one of those things where people might not have a definite need for it academically, but they will start thinking creatively and do something fun with it,” Hammett said.

White also hopes the printer will be a sort of “interest generator” — a potential-filled curiosity that could attract more students to the library and its services. Ultimately, White said staff members plan to move the printer into a more public space, where students will be able to access it without staff mediation.

But there are several impediments to that goal.

First, said library IT manager Uche Enwesi, the printing takes time. Users might need to wait anywhere between one and 10 hours, depending on the size and complexity of the item they’re printing. Staff members are developing a system that wouldn’t require students to sit next to the printer the whole time and would give priority to more urgent projects.

The library’s current university-wide printing system, Pharos, doesn’t have the ability to charge by weight or accommodate other features specific to 3-D printing. Graduate assistants sent to research an integrated 3-D printing system came back empty-handed, he said. But because the university’s contract with Pharos is up for renegotiation, Enwesi said the university’s 12 years of experience with the company could prompt a solution during the renegotiation process.

Enwesi’s other major concern is the printer’s fragility. Without panels to protect the printer’s contents, someone could easily ruin an item by accidentally nudging it mid-print.

But Enwesi is optimistic the staff will find solutions in the coming months and allow students direct access to the printer by the spring semester.

“My long-term vision is to have it out there without us interfering, telling [students] how to use it,” he said.

That vision would move the library closer toward achieving its goal of expanding printing services.

Further down the road, White envisions a 3-D printer in the Engineering and Physical Sciences Library and perhaps more in other libraries on the campus.

“Libraries are trying to become centralized places on campus for any kind of innovation and idea generation,” he said.

Anshuman Sinha, a graduate student studying finance who works in McKeldin, hadn’t used the printer but described several ideas he had for it.

Anything from pranks — “things that look like the real thing and end up on YouTube” — to “pimped-up board game pieces … and that’s just the silly stuff,” Sinha said. “It’ll be the coolest thing to have your own little factory, to get something mechanical to work.”