Chance the Rapper’s independently produced, digitally distributed — for free, no less — and surprisingly popular Acid Rap may serve as a model for future up-and-coming artists.

You’re driving alone in your car with the windows down. You flip through the FM radio tuner and come across that catchy pop song you heard once at your friend’s place. A couple of minutes pass and the song ends. Afterward, you find it’s also playing on three other stations, and the song becomes significantly less appealing with each listen. This happens every day for the next few months until the next “Blurred Lines” or “Get Lucky” replaces it.

Most of the college-aged population has grappled with this nightmare of repetition at some point or another. It’s led to gripes that musical innovation is dead or at least that it’s not what it once was. In reality, innovation just isn’t burgeoning on the radio anymore. It’s happening by way of the musical demo — the mixtape.

The primary problem with popular music today does not stem from poor writing or uninspired thinking. Neither is it rooted in whipped-cream bras or award-show twerking scandals. The main fault is in its inability to usher in new artistic voices.

The industry changes slowly because most labels are looking to produce commercially successful artists, not the more obscure ones whose album sales will flounder until a mainstream audience realizes their existence 20 years down the road.

They want Macklemore, not The Pharcyde.

Produced in a minimalistic fashion and designed to spawn hype, mixtapes have been the lifeblood of the hip-hop genre for the past several decades. Recognizable artists such as 50 Cent, Nicki Minaj and Drake all found their voices via mixtapes that garnered critical acclaim. D.C.’s own Wale similarly paved the way for future success from his efforts on 2008’s Seinfeld-inspired The Mixtape About Nothing.

More than one artist has explained that the mixtape period in a career often works out to be among his or her most creative and productive (see: Wayne, Lil). Without the stifling pressures of a major label, rappers have liberty to say whatever they want on their mixes. They can experiment with different sounds and ideas, and they have the freedom to find the most accurate ways to express themselves. “Mixtape is raw. I did what I wanted to do. You can’t do that on an album because other people gotta eat off that album,” Wiz Khalifa said in an interview with Complex.

In the 2010s, just about anyone can make a mixtape. With programs such as GarageBand and Logic Pro, commoners can easily act as their own producers. While sound quality will inevitably suffer, ideas can be fleshed out in ways simpler than many in the business thought possible 30 years ago.

Clayton Krollman, a sophomore education and English major, spent several days during the summer recording a mixtape with his group, Kissing is Gross. Each of the mixtape’s seven songs were recorded with his iPhone in a one-take format and posted on the music discovery site Bandcamp, which allows for donations if the listener feels inclined.

The songs are raw and expectedly unpolished, but there is genuine merit in the work. Krollman said the tape, Beauty Sleep — self-defined as punk, pop and ska, among several other styles — was never meant to be heard by more than family and friends. But he added that if he were to pursue a more commercial success in music, a mixtape would be the best way.

“We made [Beauty Sleep] for fun,” Krollman said. “But if I wanted a career, I’d probably make a bunch of demos and go around to studios, ask them to spend seven minutes of their time listening to me. I think Kanye [West] used to load up demos in a backpack and take them around, too.”

With the Internet permeating mainstream culture more each year, these self-made records will only increase in importance. If a mixtape was helpful in getting signed in the past, it might soon be a necessity in the musician’s resume, regardless of his or her genre. And if more musicians start their careers off with mixtape demos, the competition may enable higher quality writing and production.

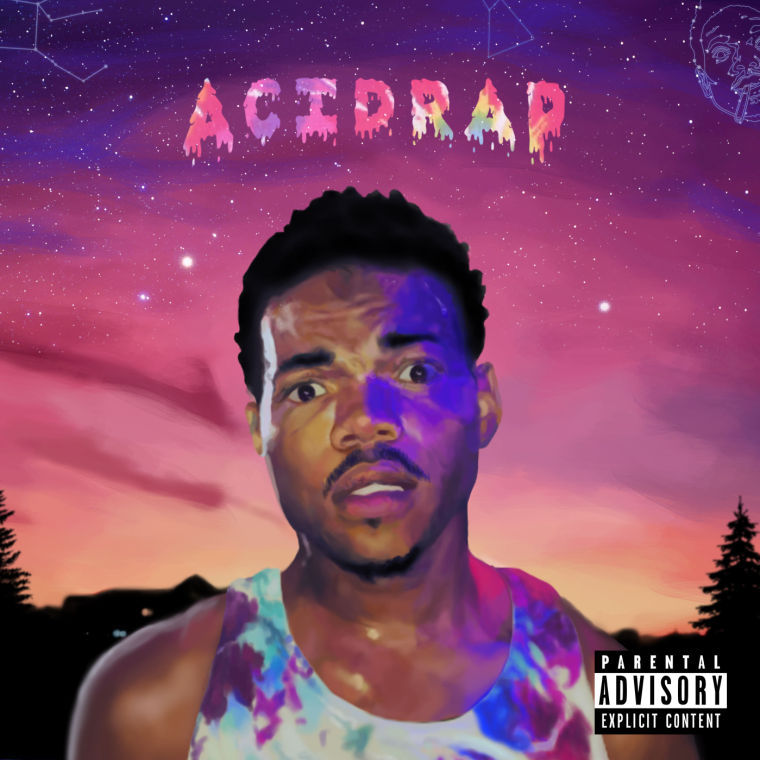

When an artist such as Chicago-based Chance the Rapper finds both his distinct sound and a large Internet following with a mixtape such as Acid Rap, new markets open up. If he signs to a major label, his sound will be refined to a point but likely still will hold the same appeal. If the artist gets big enough, copycats will follow. Thus, the landscape is changed forever.

The mixtape market is young enough that, as of yet, it stands mostly untapped by greedy hands. It is expanding, however, and some are taking notice (Acid Rap peaked at No. 63 on the hip-hop charts after being sold without Chance’s permission; it can be downloaded for free on his website).

The industry could use some restructuring on all fronts, and the proliferation of underground mixtapes could be the spark plug for improvement. Call it crazy, but someday — maybe soon — when you’re driving alone in your car, you might be able to flick through a few FM radio stations and fall in love with a new artist almost every time.