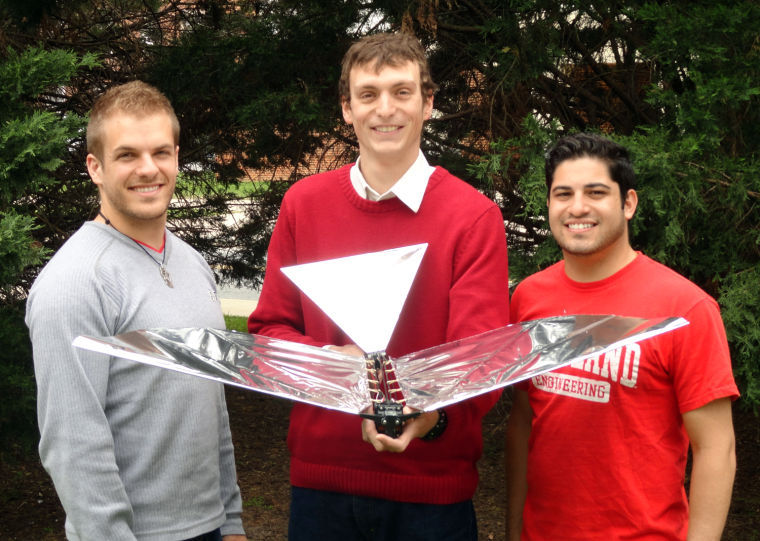

(L-R) Grad students Luke Roberts, John Gerdes, and Ariel Perez-Rosado with Robo Raven.

It’s not a bird, nor is it a plane — but Robo Raven, a robotic bird developed by a group of university professors and graduate students, is taking to the skies.

After five years of development, the work of two engineering professors and five graduate students is making national headlines with Robo Raven’s first successful flight on April 30. The robotic bird is the first flapping wing robot to have independently controlled wings, and it means engineers are one step closer to creating a machine that accurately mimics a real bird’s flight pattern.

Each wing motion is programmable, an extremely difficult feat, according to Dr. Satyandra K. Gupta and Dr. Hugh Bruck, the professors responsible for the development of this project.

“We can program the desired wing velocity and position,” the professors wrote in an email. “This allows us to closely replicate the flapping motions of bird wings. Previous flapping wing robots were driven by a single motor. This makes wing motions coupled, and only allows changes in flapping speed.”

Because each wing is independently controlled, Robo Raven can generate aerodynamic forces that enable it to be highly maneuverable and fly like a real bird. It can quickly dive, turn and even avoid colliding with other objects, as well as glide in windy conditions to minimize energy consumption. Robo Raven’s flight motion looked so realistic a hawk attacked it multiple times during a test flight.

The professors are also excited about the surveillance and environmental capabilities Robo Raven could bring.

“It can even scare away other birds from places where they may cause serious problems, like airports and agricultural fields,” they wrote.

Ariel Perez-Rosado, one of the doctoral students, said the biggest challenge was making the bird light enough to fly while still retaining the ability to digitally control each wing.

“The reason this has never been done before is because two motors can be heavy,” he said. “We had to spend months testing and performing trials before our first flight, but we eventually found a way to change the weight balance to where it could stay in the air.”

In order to make each wing separate, the robotic bird needed larger batteries than previous models, so the group had to tinker with the other pieces of the robot to reduce its weight. They used new manufacturing technologies, such as 3-D printing and laser cutting, to create structures that kept Robo Raven’s weight down and new wing shapes with a large aerodynamic lift to help it take flight.

The professors initiated the project — Gupta began developing early versions of Robo Raven five years ago — but students Luke Roberts, John Gerdes and Perez-Rosado did most of the experimentation, which proved to be a valuable learning experience in both patience and engineering, Roberts said.

“They headed up the project and gave general pointers, and then it was our job to figure out which parts to use, do the testing and come up with wing designs,” he said.

With flying robots, any unsuccessful flight can damage the delicate technology. Still, Roberts said Gupta’s and Bruck’s input enhanced the collaborative effort and led to the bird’s successful launch.

“The professors work really hard on their research and give the best opportunities to students,” he said. They care about our success as well as their own, and that’s something you don’t see all the time.”

The crew isn’t done working on the robotic bird, Gupta and Bruck said, as there are still many potential applications it could achieve with further development.

“We hope that Robo Raven will soon be carrying cameras and sensors to monitor areas for potential hazards that are not currently accessible by other means,” they wrote. “In addition, we have had a number of requests from hobbyists who want to start playing with it.”