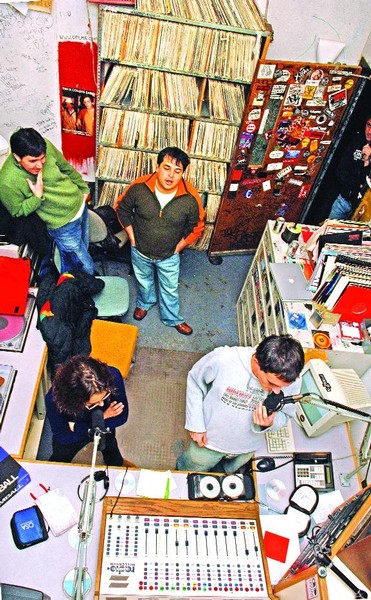

The cluttered, yet vibrant studio of WMUC serves as the backdrop for the lively shows that have been broadcast around campus for decades.

Behind the heavily stickered and graffitied doors of WMUC 88.1 FM above the South Campus Dining Hall, ratty chairs losing their stuffing line the back wall of the lobby. The station’s main room contains typical office fare – desks, mailboxes and a computer.

Then you see the barren box spring and mattress in the corner where many a WMUC’er has caught up on some sacrificed sleep or relaxed during a broadcast.

At WMUC, the dedication to the art of radio overpowers any dedication to classes. It’s a place where no-name bands haul their guitars into the studio to perform during late-night time slots, where students analyze politics on their 6 a.m. shows and where a rich history of aspiring journalists and musicians have gathered to fill the airwaves.

“WMUC means a lot to a lot of people,” WMUC Operations Manager Colm Atkins said. “You come in and its really a tight-knit group.”

But following news last week that Baltimore National Public Radio affiliate WYPR 88.1 FM planned to expand its signal, which could knock WMUC off the radio dial, WMUC DJs and groupies were dumbfounded.

“People at the station walk in and they’re just like deer in headlights,” Atkins said. “They’re just scared and they want to know what’s going to happen.”

Atkins said he spends about 20 hours a week at WMUC making sure the station is running smoothly. Though none of the 150 DJs, fill-ins and staff members at the radio station are paid, the station is manned 24 hours a day during the semester.

“It’s really something people care about,” Atkins said. “People are putting in hours and hours and hours for no money and they don’t care.”

It’s not that WMUC is widely popular. Its dinky, 10-watt transmitter only has a 10-mile radius, though most have problems getting a clear signal past Cherry Hill Road. During a good show, streaming Internet listeners number only in the 20s, Atkins said. Accurate numbers of listeners for the FM station can’t be deduced, but people at WMUC know the score.

“Having the FM broadcast is more sentimental value,” WMUC Music Director Rohan Mahadevan said.

According to the staff, if WMUC is bumped off air it may be another example of college radio’s demise.

Thanks to the streamlining and automation of the radio industry, many professional and college stations around the country have opted to pre-record radio shows, interjecting perfectly edited chatter and two-minute commercial breaks between songs. The days of college DJs perfecting live small talk while cueing the next record have disappeared, replaced by pre-selected iTunes playlists.

WMUC, in many ways, is the last of a dying art, being the last existing college radio station broadcasting in the Washington area.

“The college radio envisioned in the ’70s and ’80s that was very free form and all over the place is just on its way out,” Atkins said. “Bands like Death Cab [For Cutie] that used to thrive only on college radio can now sell out DAR [Constitution Hall] in 25 minutes.”

But even WMUC, though somewhat dated, isn’t completely devoid of new technology.

“Kids come in now and just play off their iPod,” Mahadevan said. “They’re not sifting through CDs and coming in with a big stack and not knowing how they’re going to play it.”

Regardless of how the DJs plan their shows, the history of the station is worth protecting, staff said.

The station first broadcasted in 1937 and takes pride in being one of the oldest college stations in the country. After a brief hiatus during World War II, the station relocated to a shower stall in the basement of Calvert Hall.

The studio has been graced by performances by famous artists like The Get Up Kids, Elliot Smith and Q and Not U, and Mahadevan said the long history adds to the charm of working at WMUC. Famous alumni like CBS Sports’ Bonnie Bernstein and Comcast SportsNet’s Chick Hernandez were also once part of the staff.

“It’s great to know you’re sitting in the same chair as the guy from Q and Not U,” Mahadevan said.

While the focus of radio may be music, WMUC has offered more than that. Former Student Government Association presidents Tim Daly and Aaron Kraus had their own radio shows, interviewing politicians and university officials every week. Last year, Kraus interviewed Gov. Robert Ehrlich .

The sports department also sometimes broadcasts on the FM station, though most of the games stream online.

Nick Sekkas, co-sports director of WMUC, said though WYPR’s takeover wouldn’t impact sports broadcasting too much, the move would be “disheartening.”

“This station has really had some glory days and it would be sad to see it not have an FM frequency,” Sekkas said. “It would be a shame to lose that. We really need to hang onto it.”

Atkins said the fate of the station is not clear. While WYPR is within its legal rights to overrun WMUC’s signal, it is hard to predict its impact on the station until WYPR officially expands.

Atkins said the most likely alternative would be to continue streaming the station online. While WMUC already streams on its website, it would be a significant decrease of credibility, he said.

“It’s just that there is so much history at the station, it would be the end of an era,” he said.

Other WMUC DJs shared Atkins’ sentiments.

“If WMUC goes off the air, a great disservice is being done to the area,” said Chris Berry, a freshman communication major who hosts a show with his roommate. “It’s not just Sean Hannity or something on the radio, it’s different. We don’t have wild reach but the people appreciate we’re different.”

In the coming months, WMUC staff said it may look into a “Save WMUC” campaign to convince WYPR to think twice about expanding its signal.

“I think we really need to fight this with the media and really get the national public hating WYPR,” Mahadevan said. “We should write to Oprah and get her to help us out. I could make some real tears for Oprah.”

Contact reporter Sam Hedenberg at hedenbergdbk@gmail.com.