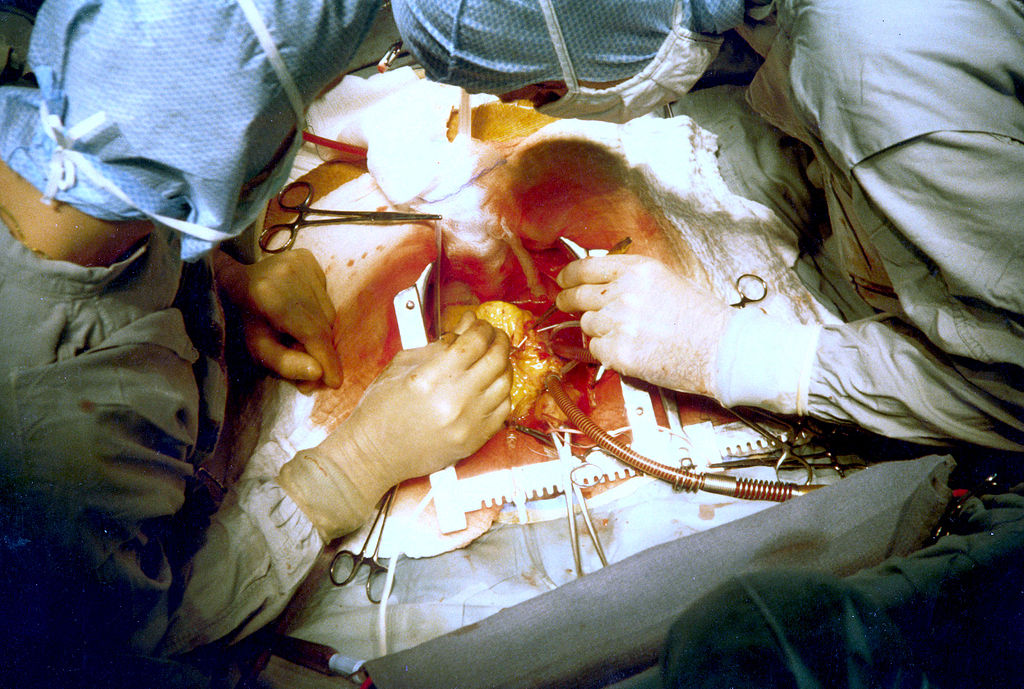

Appropriately located in the heart of Cape Town, just off Nelson Mandela Boulevard, there runs a street named after Dr. Christiaan Barnard. A couple of kilometers away sits Christiaan Barnard Memorial Hospital. In 1967, Barnard performed the first successful human-to-human heart transplant, and in doing so ensured that his name would never be forgotten.

Afterwards, the South African government attempted to use Barnard’s image as a young white success story to improve its own global image during terrible apartheid repression. Barnard, somewhat unwillingly, went along, while several of his colleagues were forced into exile for speaking out. The story became more complex in 1991, when Barnard brought to light the contributions of Hamilton Naki.

Naki, a black South African born in a poor rural village in the Eastern Cape, was hired to tend to the University of Cape Town’s gardens in 1940. He thus began an unprecedented ascent into the operating room, despite having no formal education. By the late 1950s, he was cleaning lab animal cages at the university. In the 1960s, he was anesthetizing animals and doing surgeries, including liver transplants (considered to be among the most difficult surgical procedures). In the 1970s, he was instructing university faculty in transplant techniques. Upon his retirement in 1991, Barnard described Naki as “a better craftsman than me.”

At the end of the day, Naki went home to his one room house, sans electricity and running water. When he retired, he was given a gardener’s pension. In the years following apartheid, his story made national news. For many, he became a symbol of the repression of black achievement during the apartheid years (though he did not, as it was erroneously reported, participate first-hand in the Barnard’s famous heart transplant). Between 2002 and 2004, he was given a series of awards and acknowledgments, including an honorary master’s degree from the university where he’d worked (bestowed upon him by Nelson Mandela’s wife, Graça Machel).

There are no buildings in Cape Town named after Hamilton Naki. He died in 2005 in Langa Township, where 72 percent of households make less than $230 per month. He passed away, of all things, from heart trouble.

Christiaan Barnard died in 2001. His contribution to the world survives him. In a microcosm of the South African apartheid years, so too does the smaller-scale legacy of Mr. Hamilton Naki.

Jack Siglin is a senior physiology and neurobiology major. He can be reached at jsiglindbk@gmail.com.