It’s been argued on BBC Radio (April 1 and again on April 9) that the Russian-Syrian victory in Palmyra against ISIS, as important as it might be morale-wise for the Russians, Syrians and the West, doesn’t mean much strategically; ISIS in Syria is kind of an offshoot of ISIS in Iraq, which is where its real strength lies and is where the group got its start. As such, the real prize would be Mosul — the second largest city in Iraq, which ISIS captured in June 2014 and from which it first proclaimed the formation of a caliphate.

Mosul is located on the Tigris River upstream from Baghdad, which is located at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers farther south. In other words, Mosul is ISIS’s real strategic stronghold, and its destruction or capture by combined Western, Iraqi and Kurdish forces or Russian-Syrian forces would essentially defeat ISIS and come close to wiping it off the face of the Earth.

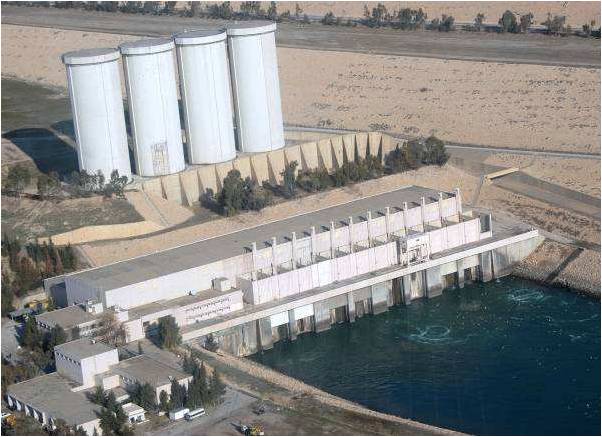

If so, can this logic perhaps belatedly explain the ignoring of the United States for so long the inherent weaknesses in the Mosul Dam upstream from the city, particularly in more recent months? After all, the United States forcibly brought correction of the Mosul Dam’s problems to a halt in 1991 by its invasion and blockade of Iraq. The dam was built on an unsound geological base, and starting in 1988, the problem was being corrected by building the Badush Dam downstream from it to catch the waters if and when the Mosul Dam should break. The new dam was 40 percent complete when construction on it was halted in 1991, and it lies there fallow and unfinished to this day.

Are these dams and the U.S. failure to deal with their instability and incomplete construction now part of U.S. military strategy in its attempts to defeat ISIS (even if it wasn’t before, when the neglect of the dam by the U.S. started in 1991)? After all, if the Mosul Dam breaks before the catchment dam is completed — as no work is now apparently being done — it will, according to the theory expressed above, solve the United States’ problems in respect to ISIS by effectively or mostly wiping it out, or at least wiping out its main geographic base, which largely allows it to consider itself a caliphate.

When it reaches friendly Iraqi territory downstream , although it will still kill a lot of people not involved with ISIS, these effects perhaps can be managed so as not to undermine or destroy the Iraqi government in Baghdad, as U.S. government might be currently reasoning. After the dam break, the wave of water will only be about 13 feet high when it reaches Baghdad, as opposed to being as high as 80 feet when it reaches Mosul. That’s still a lot of water, but maybe, naively, it doesn’t seem like so much to the U.S. government when compared with the size of the wave that will strike Mosul.

The only problem is, the wave of water is going to wipe out a lot — some say up to million — of innocent non-ISIS civilians in Mosul, not to even speak of its effects downstream. Also, even if the wave’s effects in Baghdad turn out to be minor (or shall we say manageable?), what about its effects on the towns between Baghdad and Mosul in friendly territory, where the wave’s size will be less than 80 feet but surely greater than 13 feet?

But from the United States’ point of view, this still might be preferable to using military force to get ISIS out of Mosul, even if fewer people might be killed by bombs.

Why would a dam break be preferable to the United States? The blame and recriminations would surely be greater in the case of using military force and drone strikes, which would be more obviously caused by the United States, than they would be in the case of a dam break. But if the United States thinks it can get itself off the hook by having a dam break that would largely be considered a natural disaster by the rest of the world, it might find itself having to do some more explaining.

Jonathan Miller is a graduate student studying geology. He can be reached at jsmiller@umd.edu.