With conservatives (among many others) unhappy with the current presidential front-runners, a strategic run by a third party — or parties — could deny Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton the ability to win the presidency outright. If neither presumed but unpopular front-runner wins 270 electoral votes in November, then the 12th Amendment requires the newly elected House of Representatives to choose the next president just days before the January inauguration.

This situation would be truly shocking — even for this election — because the House has not chosen a president since John Quincy Adams in 1824. Since then, third parties have won electoral votes or significant portions of the popular vote. But this political environment features polarizing and relatively unpopular major party candidates and — perhaps more importantly — unprecedented amounts of money to support candidates directly or indirectly. As a result, another candidate might be able to win the electoral votes of certain states, thereby forcing an “undecided Electoral College.”

Once the House has the power to decide the next president, each state’s delegation receives one vote, meaning California’s 53 representatives have a vote equal to Vermont’s single representative. A winning candidate needs 26 delegations to win. Republicans currently lead the delegation count 33-14-3 over the Democrats, and though anything can happen in 2016, it seems as though Republicans will hold the lead in total House delegations in the next election.

An undecided Electoral College could occur in many ways, depending how certain groups react to their traditional parties’ primary winners. A third party needs to win enough states to prevent a major party from reaching 270 electoral votes. This entails winning critical “swing states” or enough “safe states” from each side. Then this party can try to eke out a victory in a divided House, in which GOP members (especially) might not be particularly supportive of either major-party nominee.

The biggest chance for a strong “third candidate” run is if Trump wins the GOP nominations and conservatives rally around a new candidate. Conservative commentators and activists have been threatening such a possibility for months now, and if sufficiently supported, a different campaign could push conservatives to the polls in November. A slightly different scenario has disaffected conservatives and libertarian-leaning Bernie Sanders supporters rallying behind a Libertarian candidate to spite both their parties. These situations create two specific possibilities that are discussed here: the Mattis model and the Johnson model.

The Mattis model: Conservatives rally around an independent James Mattis

Many conservatives are furious and fearful at the thought of a Trump candidacy. They worry he will hurt conservative Republicans in down ballot elections for the Senate and House because, faced with a choice between Clinton and Trump, many might stay home. (Not to mention conservatives’ dislike of many Trump policies.) In an effort to still get these conservatives to the polls, conservatives could rally around retired Marine Gen. James Mattis. His candidacy has been discussed widely, and for them, he’s a better choice than Trump, Clinton or Sanders. Plus, many conservatives believe that a majority of House delegations will be Republican, and relatively anti-Trump conservatives at that.

The Mattis model requires Mattis’ willingness to run first and foremost, unless a similar candidate can be found. The next challenge for Mattis would lie with being strategic in his campaign style. His candidacy will surely help draw conservatives to the polls, but if the vote is too evenly split between Trump and Mattis, then Clinton/Sanders will win everywhere. Furthermore, he is too limited in time, organization and resources to run a truly nationwide campaign.

So Mattis needs to target a few vital swing states with large military populations or aversions to one of the major candidates. His best chance would be to target swing states Virginia and Florida, home to large veteran populations. By focusing his campaign there, he could push his military and foreign policy credentials, outsider status and personal integrity compared with his opponents. His domestic policies must be noncontroversial and his economic policies conservative enough to attract conservatives. It’s a difficult line to walk.

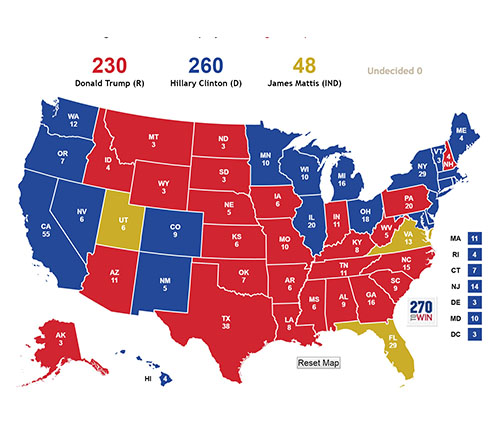

Two victories in Florida and Virginia would give him 42 electoral votes, Trump 234 and Clinton/Sanders 262 (obviously Mattis could win more states and the two front-runners could have a slightly different balance of states). Trump would also have to win two more states than Mitt Romney did in 2012. Here’s what the electoral map could look like:

If Mattis ran a targeted campaign and Trump won at least one blue-leaning “rust belt” state, no candidate would win a majority. (Screenshot: 270towin.com electoral simulator.)

I believe this model will be attractive for anti-Trump conservatives, provided the general is willing. It’s more than likely that the general election costs Trump some traditional Republican states (through a split vote), which would push Clinton over 270. But at the very least, they will get conservatives to the polls — and they’ll have a chance to get Mattis elected in the House. Potentially, if Trump won Pennsylvania and Clinton won Virginia, Mattis would only need Florida. Still, this option has a low chance for success and requires a very careful approach.

The Johnson Model: The Libertarians carry the inland West

Former New Mexico Gov. Gary Johnson (once a Republican, now a Libertarian) could try the same traditional “swing state” strategy as Mattis, but I think his best chance is to win a plurality in key Western states like New Mexico, Colorado and Nevada. These states have had leaders of both parties at the statewide level and seem more friendly to more libertarian policies. If he focused on these states (as well as GOP states like Wyoming), he can win enough delegates to deny Clinton or Trump. This strategy only comes to fruition if many (if not most) Sanders supporters defect to Johnson or at least don’t vote Clinton, and conservative Republicans commit to Johnson.

Take the 2012 electoral results map. Sanders supporters, disaffected, wouldn’t help Clinton stop Trump in Pennsylvania, where he’s already polling well against Clinton. Everything else is the same (or changes have little net effect), except the three key states that give Johnson 20 electors to Clinton’s 264 and Trump’s 254. The issue, of course, is how Johnson’s candidacy affects other states. A regional focus gives him the chance in the House. A national focus might mean a Ross Perot situation in which Johnson wins a higher percentage of the popular vote, but not one state. Another key assumption is that angry Sanders supporters flock to Johnson to punish the Democrats rather than Jill Stein, a Green Party candidate. Johnson would have to focus on social issues and electability — he did poll in double digits in a three-way race that also featured Clinton and Trump.

Here’s his map with the three critical states, though he could also win states in the Republican West and cause some interesting three-way races in other states:

This unlikely possibility requires Johnson to perform well in the Southwest while Trump dominates in the ‘rust belt.’ (Screenshot: 270towin.com electoral simulator.)

Final thoughts

The models presented make the same key assumption: Candidates focus on winning a few particular states and other states go roughly the way they have the last few cycles, even by a plurality. That’s a particularly simplistic assumption, but it reduces the number of variables to consider.

At the end of the day, many Americans vote for the lesser of “two evils” or don’t even bother voting. Perhaps that’s the probable outcome this year, too. But as we’ve seen, there’s a lot of unrest among members of both parties, and the two frontrunners are well-known and popular. Anything can happen in this election, so it’s important to highlight the intriguing possibility that no candidate wins a majority of electoral votes. It’s just one interesting possibility among many with serious consequences.

Just imagine if there’s a rogue elector.

Matt Dragonette, opinion editor, is a senior accounting and government and politics major. He can be reached at mdragonettedbk@gmail.com.