New research from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s Appalachian Laboratory examines the population size and migration patterns of the red and hoary bats species, which together account for 70 percent of the bats killed by wind turbines in the eastern United States.

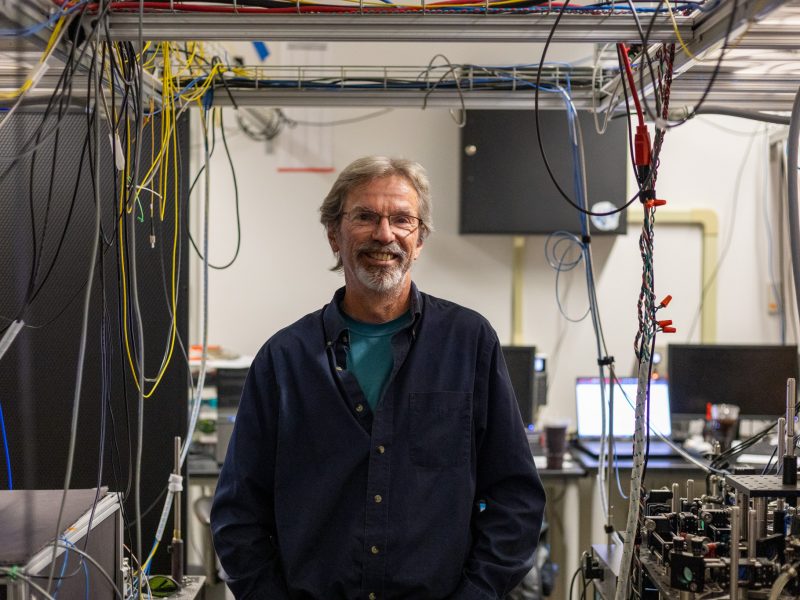

“We don’t know a lot about these bats except that they’re killed by wind turbines,” said David Nelson, a professor from the Appalachian Laboratory. “With this study, we can start to get a handle of how they’re moving around the landscape and how many are out there.”

Researchers used DNA-sequencing techniques to estimate the effective population size of the two bat species, Nelson said. To find out where the bats had come from, analysis of stable hydrogen isotope signatures revealed where the bats spent their summers and told scientists whether each kind of bat had traveled long distances before dying along the Appalachian ridgeline. Ecological Applications published the results of this research in February.

The study estimated the red bat population size was in the hundreds of thousands to one million range and the hoary bat population was in the in thousands or tens of thousands, Nelson said. “This tells us that, from a conservation perspective, we need to be more concerned about the fatalities of the hoary bat … because they [and the red bat] are killed at roughly the same rate,” Nelson said.

The study found while roughly half of the red bats killed by turbines on the Appalachian ridgeline apparently spent summers farther away from the ridgeline and the wind turbines, the hoary bats seemed to spend summers in more local locations, he said. If hoary bats spend summers in the area, that’s part of their migration route, meaning turbines constructed in that area could have a greater impact on the population.

These kinds of bats can be difficult to study because unlike some species, migratory bats don’t congregate in caves, said Matthew Fitzpatrick, a professor at the Appalachian Laboratory. The populations are huge and scattered across large regions, he said, meaning scientists don’t know much about their numbers or where they’re migrating to and from.

This was “a group of organisms that were being impacted by the wind energy development in this region, along the Appalachian ridgeline. … Any sort of energy development has impacts, but I think this was a relatively unanticipated impact,” Fitzpatrick said. “I don’t think people thought developing wind energy would impact migratory bats.”

This study is providing “a first look at the sustainability of the issue,” said Cortney Pylant, biological scientist from the University of Florida and lead author of the study.

Bats provide important ecosystem services, such as controlling insect populations, so it is important to look at how wind energy production affects these species and whether that production presents a threat to the species, Nelson said.

Studies like this have started to shed light on the scale of the impact wind energy development has on bats, Pylant said. Understanding whether these bats are being killed close to their breeding grounds or whether they traveled a long way before they were killed could help inform future development efforts, she said.

“If turbines are constantly killing bats in a certain area every year, that could have a greater genetic impact,” Pylant said. “If we get a sense of where the bats are moving, we ideally can place these wind sites in areas that have less of an effect in terms of [bat] mortality.”