A team of astronomers including University of Maryland researchers recently observed the bright flash of a supernova shockwave — the first time anyone has captured the light of this celestial event.

Researchers caught the flash of a shockwave from an exploding star — known by astronomers as “shock breakout” — thanks to NASA’s Kepler space telescope and published a paper on the observation this month in The Astrophysical Journal.

“When the star dies and runs out of energy at the core and collapses, as it’s collapsing in on itself, there’s a shockwave that gets sent out and that shockwave goes from the core of the star outward towards the surface,” said Ed Shaya, an astronomy researcher at this university.

The initial stages of a supernova can’t be observed because they occur deep within the star, Shaya said, but as the process reaches the surface, the star becomes hotter and brighter and then starts to tear apart.

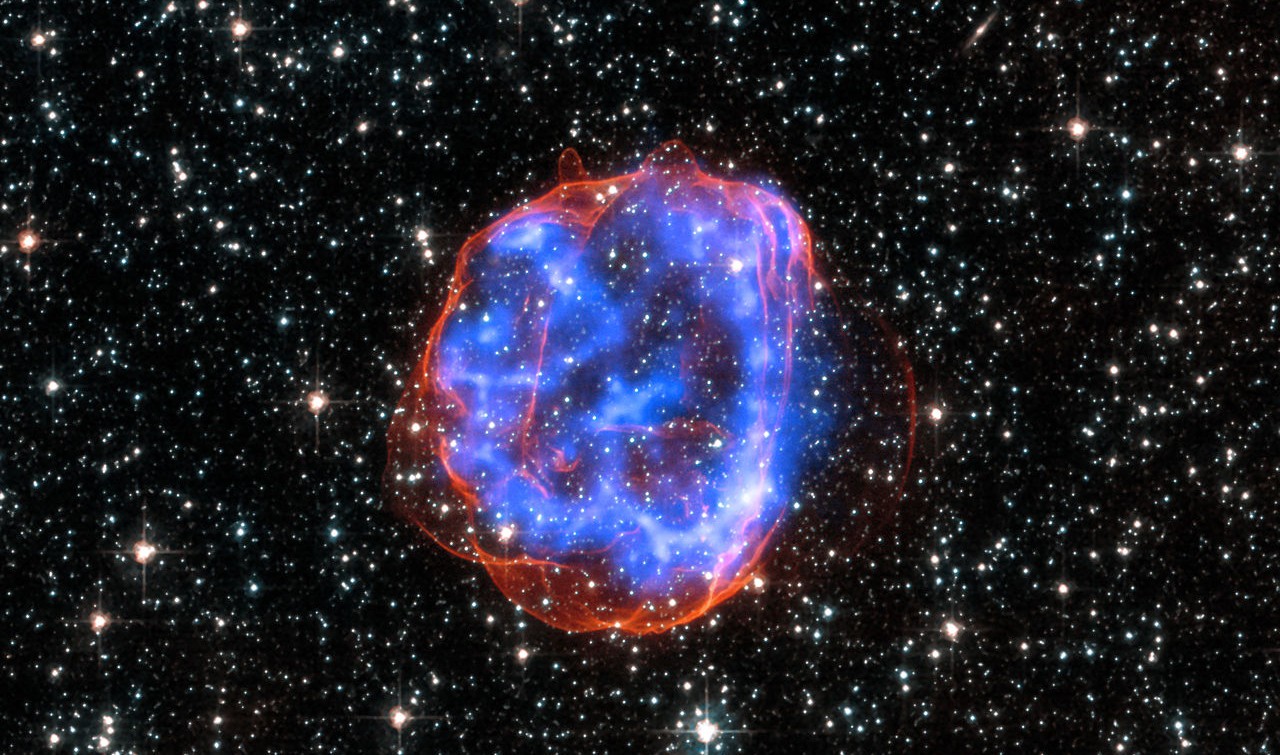

As the shockwave reaches the surface, its force throws the material from the star out into space. This collection of materials is known as the supernova remnant, Shaya said.

“What we see as the supernova is actually the remnant, expanding and becoming very big and very bright,” Shaya said.

The Kepler space telescope, a NASA observatory launched in 2009, is like a big camera that monitors a large section of the sky every 30 minutes, Shaya said. Kepler watches stars in the hope of discovering Earth-like planets orbiting them. But researchers thought that while it was staring at the stars, it could monitor galaxies as well, said Peter Garnavich, a University of Notre Dame astrophysics professor and alumnus of this university who was involved in the supernova study.

Researchers monitored some 400 galaxies for about three years using Kepler, Shaya said.

Though Shaya said they were mostly looking for activity from the black holes at the center of the galaxy, they also thought they might happen to see a supernova or two.

“We got six,” Shaya said.

Two of these were core-collapse supernovae of a red giant star, one of which showed this shock breakout, Shaya said. Scientists have always wanted to see the shockwave just as it hits the surface, when it’s at its hottest, he said — and that’s what the research team was able to observe.

“There have been theoretical calculations of what it would look like and that it would be there,” Shaya said. “We’re confirming the theory. You can’t really believe a theory until you get an observation that proves it.”

Actually observing the breakout and seeing models’ predictions of it gave some assurance that the models are accurate, Garnavich said, and that scientists really understand what happens in a supernova.

Alex Filippenko, an astronomy professor from the University of California Berkeley, who was not involved with this research, said scientists have been looking for the predicted optical flash associated with shock breakout for a long time. But a supernova doesn’t last long, so it is difficult to observe, he said.

“As a researcher who actively finds and studies exploding stars at visual wavelengths, I am excited by this discovery,” Filippenko said. “But we still don’t have a complete understanding of massive stars that explode, as evidenced by the fact that only one of the two supernovae showed a clear signature of the shock breakout.”

This observation is a significant step, but more research remains to be done on exploding stars, Garnavich said.

“[We are] continuing to look at supernovae now … looking at thousands of galaxies every year,” he said. “And we’re hoping to get some more discoveries soon.”