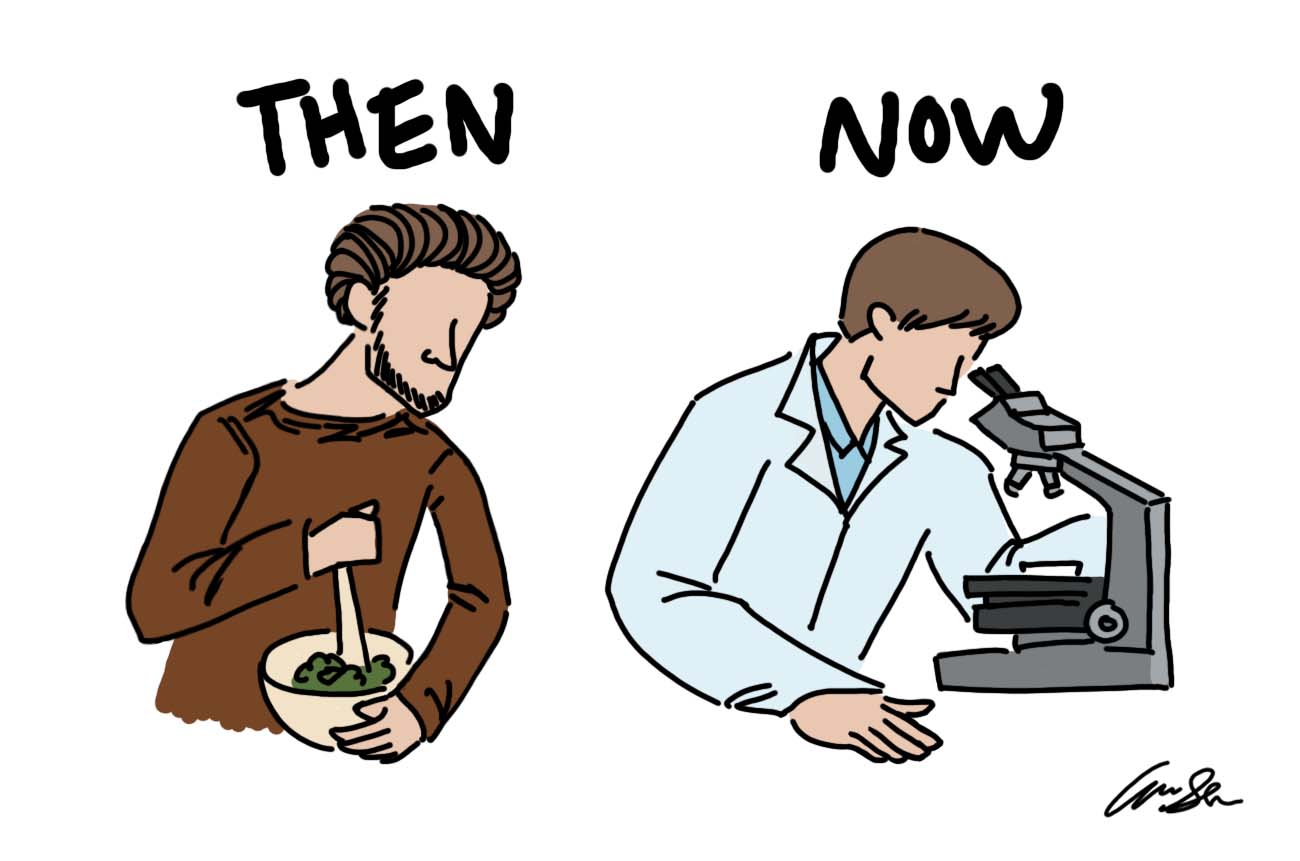

It’s the year 800 A.D., and you’re an Anglo-Saxon tribesperson. You have an eye infection, but, well, you don’t really know that. You just know that it hurts. Following a traditional remedy, you blend equal parts garlic and onion. Add some wine and some cow bile. Mix and apply it liberally to your aching eye. That’ll clear it right up in a few days.

More than a thousand years later, some scientists in Nottingham, England, are going to discover the recipe book you used. They’re going to follow the recipe, and they’re going to find out your eye salve kills MRSA.

That’s right. MRSA.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. A nasty little bacterium that can send you spiraling into sepsis or necessitate an amputation, MRSA is resistant to basically all of our common antibiotics. It’s also responsible for the death of about 20,000 Americans each year. New York Giants tight end Daniel Fells wound up in critical care in a hospital after running a 104-degree fever courtesy of a MRSA infection on his foot. Ten surgeries later, he’s still fighting the bacterium. It looks as though he might never play again.

MRSA has its roots as a nosocomial infection: a hospital-acquired bug. That makes sense, as bacterial resistance is the byproduct of frequent use of antibiotics. Kill off the ones that aren’t resistant, and you’re left with a population that can’t be destroyed with normal tools. MRSA is particularly difficult to extinguish; in fact, some strains are only susceptible to one drug. The drug can only be administered intravenously, which greatly complicates treatment. And scarily enough, we’ve just discovered some new MRSA strains that are immune to even that.

Bacteria have plenty of tools at their disposal to become resistant. Principally, they carry free-floating bubbles of DNA called plasmids. Often, these plasmids are resistance genes that arose in the population via random mutation — and they can be shared. When bacteria burst, they eject all of their plasmids, and others can pick them up. They can conjugate — a bacterial equivalent of sex — and directly share genes. They can even pick up genes from viruses. All told, bacteria are extremely good at surviving, and in many cases, that means resistance.

Every few years, it seems, an NFL locker room will have a bout with MRSA. Sometimes it’s elementary schools or hospitals. In every case, clinicians have to think hard about treatment. Every time they prescribe an antibiotic, they’re placing a selection pressure on the bacteria to become resistant. Sometimes, we can’t cure the infection at all; the bacteria simply do not respond to any treatment we have.

So how did a group of Anglo-Saxon country dwellers devise a salve that cures MRSA more than a thousand years ago? Scientists in Birmingham, England, are still working to answer that question.

Maybe somebody should go through the rest of that recipe book and see if they’ve got anything for Ebola.

Jack Siglin is a junior physiology and neurobiology major. He can be reached at jsiglindbk@gmail.com.