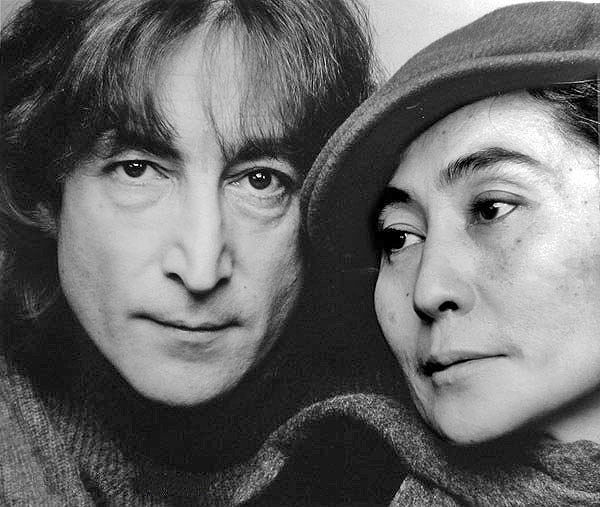

john lennon

Few songs are more influential than John Lennon’s “Imagine.”

Released in the midst of the Vietnam War in 1971 as anti-war sentiments skyrocketed in the U.S., the song was a powerful ode to unity and peace that captured the feelings of many at the time. It was a clarion call for all those who dreamed of a better world — one filled with empathy and understanding, and absent of resentment and violence.

The song’s revolutionary message — as well as Lennon’s anti-Nixon and anti-war propaganda — prompted a four-year effort from the Nixon administration to deport the former Beatle and his wife Yoko Ono in 1972. At a time when a plurality of Americans was against the Vietnam War, Lennon and his yearning for pacifism became an undeniable threat to U.S. wartime efforts in Southeast Asia.

Featuring Lennon at his finest — a weary visionary unmatched in his introspective lyricism and the unorthodox lens through which he viewed the world — the song has remained a fixture in popular culture.

Elton John regularly performed “Imagine” during his 1980 world tour. The song was broadcast to more than one billion people on what would have been Lennon’s 50th birthday, in October 1990. Since 2005, it has been played at every New Year’s during the ball drop in Times Square. An eclectic assortment of artists (Stevie Wonder, David Bowie, P!nk, Lady Gaga, Etta James and Neil Young, among many others) have performed or recorded their own versions of the track.

But Lennon’s influence spans much further than the iconic ballad.

A warrior for peace and equality

Born in wartime England on October 9, 1940, Lennon was destined to be a transformative figure in the anti-war movement. In 1967, he began his role as an unabashedly pro-peace public figure when he appeared in the anti-war comedy How I Won The War, his only appearance in a non-Beatles full-length film. Two years later, in 1969 — the same year he left the Beatles — he released the song “Give Peace a Chance,” which became an anthem for the anti-Vietnam and counterculture movement at the time. He and Ono also participated in two weeklong “bed-ins,” non-violent protests against the Vietnam War that turned into a media spectacle.

Following his departure from the Beatles, Lennon released eight solo albums filled with commentary on war, inequality and his desire for unity across all mankind. His debut solo, 1970’s album John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, was a commercial and critical success that included the song “Working Class Hero,” a seething indictment of wealthy elites’ exploitation of the middle class (“Keep you doped with religion and sex and TV/ And you think you’re so clever and classless and free/ But you’re still f—ing peasants as far as I can see.”)

His third studio album, Some Time in New York City (1972), touched on the topics of women’s rights, racial tensions in the U.S. and Britain’s contested role in Northern Ireland. In August of that year, he performed two benefit concerts in Madison Square Garden for patients of Willowbrook State School mental institution; they would prove to be his final full-length shows.

Through all this, it became clear that the post-Beatles Lennon had only one goal: to spread positive messages through his public actions, his music and the media attention he inevitably garnered wherever he went. From “Give Peace A Chance” to “If everyone demanded peace instead of another television set, then there’d be peace,” he remains one of the most quotable anti-war figures of all time, as well as an icon inevitabily referenced by activists and pacifists of every generation.

A critic of the music industry

In 1962, Lennon began to resent the constraints put on him by the commercial music industry. At that time, Brian Epstein, then the Beatles’ manager, pushed the group toward a more mainstream image. Lennon was resistant at first, but later complied, saying, “Yeah, man, all right, I’ll wear a suit. I’ll wear a bloody balloon if somebody’s going to pay me.”

In 1965, he began to worry that thousands of screaming fans who attended the band’s concerts were overshadowing the main point of the shows: the music. The song “Help!,” Lennon later admitted, was in large part about his fears that the concerts were negatively impacting the band’s musicianship.

After spending eight years as a member of one of the most influential and highest-grossing bands of all time, Lennon refused to dilute his controversial thoughts with the platitudes found within popular music. His eight solo studio albums were a mixed bag in terms of commercial and critical success, but Lennon never seemed to care. Songs like “Woman Is The N—– of The World” and “Tight A$” were abrasive and unconventional, and Lennon undoubtedly knew they would be met with pushback. But that never stopped him.

In 1978, he re-endorsed his 1966 comment that the Beatles were “bigger than Jesus,” highlighting his unhappiness as a member of the British boy band, even though it was one of the industry’s most successful.

“I always remember to thank Jesus for the end of my touring days,” Lennon said. “[I]f I hadn’t said that the Beatles were bigger than Jesus and upset the very Christian Ku Klux Klan, well, Lord, I might still be up there with all the other performing fleas! God bless America. Thank you, Jesus.”

A proponent for experimentation in popular music

In the Beatles’ early years, the group made a name for themselves with love-soaked pop tunes devoid of any substantive lyricism, something that Lennon matter-of-factly commented on.

“We were just writing songs … pop songs with no more thought of them than that — to create a sound,” he said. “And the words were almost irrelevant.”

All that changed in 1967 — around the same time Lennon was introduced to LSD — with the release of “Strawberry Fields Forever” and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Largely credited to Lennon’s songwriting, the group’s fresh psychedelic sound brought experimental musical elements, cryptic lyricism and kaleidoscopic sonics to the forefront of American culture.

No longer did the Beatles sing short little ditties meant to warm the hearts of fangirls across the world. Their music became compatible with the growing psychedelic and hippie movements of the ’60s and ’70s. This departure from pop for experimental was a passing fad for Paul McCartney, who would continue to make radio-friendly music during his solo career, but it was just the beginning of a lifelong commitment for Lennon until his death in 1980.

Critics described much of his solo music as “unlistenable,” among other not-so-kind descriptions. At face value, those comments seem insulting for someone as consequential as Lennon. Yet, they conceivably could have been complementary for him, as they proved his willingness to defy the expected.

Groups like Tame Impala, Animal Collective and the Flaming Lips are able to incorporate eccentric elements in their music in large part because of the influence of Sgt. Pepper’s and Lennon’s solo work. The trippy tracks proved that beloved music could also be weird, even to the point of quickly swirling through a tunnel of LSD-inspired madness. Listeners and critics alike will undoubtedly compare all concept albums to Sgt. Pepper’s, and it will take one hell of an effort to transcend its musical quality and impact, even today.

Overall, we will remember Lennon fondly, even if reservations about his personal character remain. An advocate for self-expression, he fearlessly defended ownership of individuality; a never-ending voice in favor of peace and the marginalized, he cemented his legacy as a force for change; a unique and uncompromising mind, he changed the perception of pop and rock music forever.

All this in mind, it’s hard to imagine a world without him.