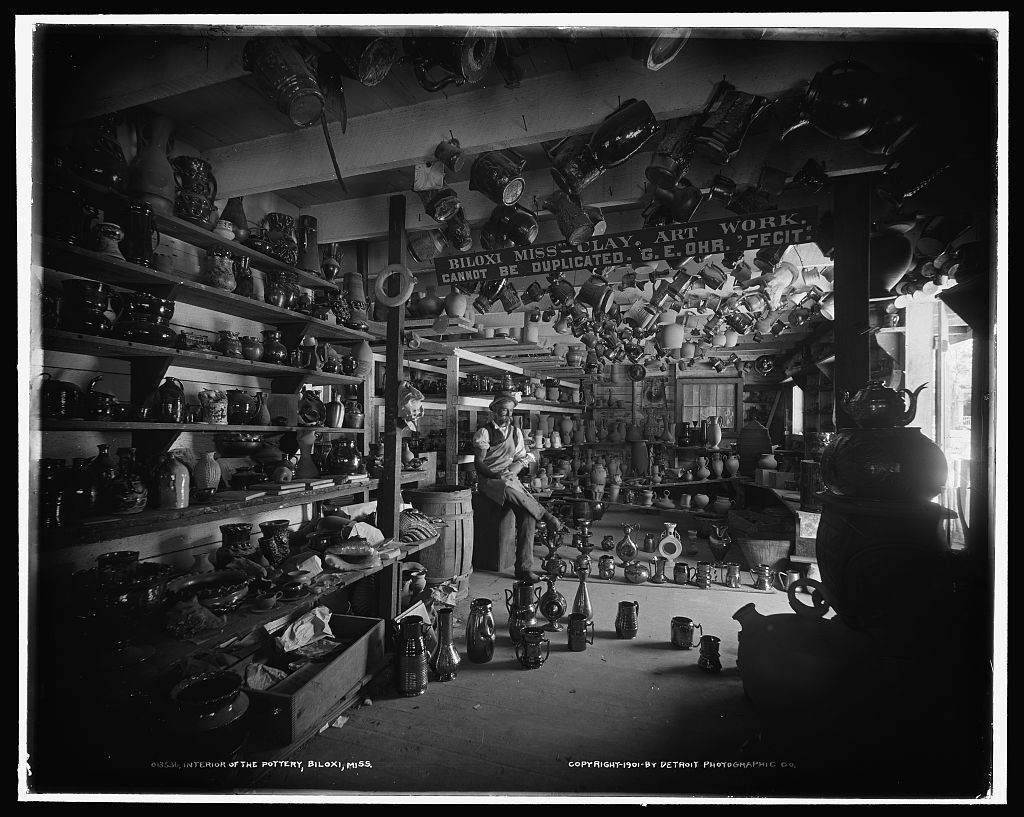

George E. Ohr, the Mad Potter of Biloxi, at work in his eccentric Mississippi studio.

There’s El Greco and there’s Gego. And then there’s the Mad Potter of Biloxi.

As far as nicknames go, I think I’d take George E. Ohr’s any day.

Ohr, the Mad Potter, is one of 18 artists, studios and companies whose pottery and glasswork are on view in a small exhibition that opened Sept. 28 at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

The exhibition explores processes of ceramics and glasswork from the 1880s to the 1920s.

“We have this really wonderful collection of hundreds and hundreds of pieces of art pottery and glass made in the U.S. … in the height of the Arts and Crafts movement,” said Bonnie Campbell Lilienfeld, the museum’s assistant director of curatorial affairs.

“It’s a really good representative collection of art pottery and glass makers in the U.S. at the time,” said Lilienfeld, who curated the exhibition. “There aren’t so many standout objects, [but] it’s really strong in its representation.”

Among the pottery and glass makers on view are Rookwood, a Cincinnati-based house; Steuben, a Corning, New York, glassmaker; and Tiffany, the crown jewel of decorative glass.

The only two individual artists on view are Ohr of Biloxi, Mississippi, and Adelaide Alsop Robineau, a ceramist from University City, Missouri.

Ohr (1857-1918) was known as an eccentric, and the pieces on view expose that quality. Two highlights are ceramic top hats, one portrayed at 9 a.m., the other at the end of the day. The morning hat is starched, upright and befitting the high-class wearer. By the close of business, the hat has bent and wrinkled, folding onto itself into an utter limpness well captured in clay.

Robineau (1865-1929) was a wealthy housewife who took up the craft after having her children, creating ornate, luxurious works of pottery. Her carefully formed and carved pieces on view are some of the most awe-inspiring of the show.

Ohr and Robineau present portraits of what many Americans perceived the Arts and Crafts movement to be: on the heels of the industrial revolution, a rejection of the mass-produced and a return to the homespun. In reality, Lilienfeld said, it was quite different.

“People have this sort of romanticized view that it was all handcraft in response to industrialization,” she said. “And it certainly was that to some degree, but … it was an industry.

“There was a lot of handcraft involved, but you know they used molds and machinery, so I’ve always found the Arts and Crafts movement really interesting for that.

“Even at the time, they had this sort of aura of handcrafting, of getting back to earlier styles of manufacture and decoration,” Lilienfeld said. “But at the same time, they were companies that were trying to make money; they weren’t just artists in the studio.”

In fact, the rising middle-class incomes and lower production costs brought about by industrialization were what made such purchases possible in the first place. People were able to own beautiful things in their homes without breaking the bank.

In some cases, the pieces even reached the Smithsonian not as art but as public-relations objects. Various manufacturers, including Rookwood, sent the institution their pottery for inclusion.

“We actually have original letters from some of the makers really encouraging the Smithsonian at the time to display their things to the best advantage and giving them suggestions about how to put the things on display,” Lilienfeld said.

While the pieces were mass-produced, though, they and houses that made them showed a distinct humanity. In many cases, the craftwork, a fine job in an era when work was hard to come by, was done by women.

Paul Revere Pottery of Boston employed immigrant women, teaching them a valuable, marketable skill. Arequipa Pottery in Fairfax, California, was produced in a sanatorium for women suffering from tuberculosis, Lilienfeld said.

In numerous cases, the pottery presented a worldly view. Rookwood employed Japanese artists to faithfully capture the Asian look its customers desired. In one case, a French artist created fantastical glazed pottery but took his method home to France after a short American stay. Nobody knows the secret to his process, Lilienfeld said.

As America seems to have become obsessed with craftiness once more — from Pinterest and Etsy to the new Handmade At Amazon craft venture announced Thursday — one can see the unique silliness, unabashed capitalism and undeniable beauty of the Arts and Crafts movement beginning again.

“Art Pottery and Glass in America, 1880s-1920s” runs at the National Museum of American History until April 24, 2017.