Screen shot courtesy of news.gatech.edu

When Alfred Hitchcock released Psycho 55 years ago this month, Americans couldn’t wait to get a glimpse of one of the most provocative pictures of the time. It was a surprise unlike anything audiences had seen before. Suspense combined with a bloody murder scene lingered in people’s heads. Anyone could be hiding an unstable mind; any friendly stranger could be a Norman Bates.

But if it was just a movie, then why was it so terrifying?

Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology have finally put their finger on why horror films are so powerful.

A study published this month in Neuroscience titled “Neural evidence that suspense narrows attentional focus” explains what audiences long have felt: Scary movies draw you in, and they make you feel unsafe, even if you’re lounging on the couch covered in popcorn.

Sophomore Austin Revels knows the sensation well. He looks for it.

“If I’m willing to get engrossed in the movie then it feels real, and that’s the feeling I want,” the computer science major said. “I feel like I’m getting the fight-or-flight response from the movie.”

The science can explain why.

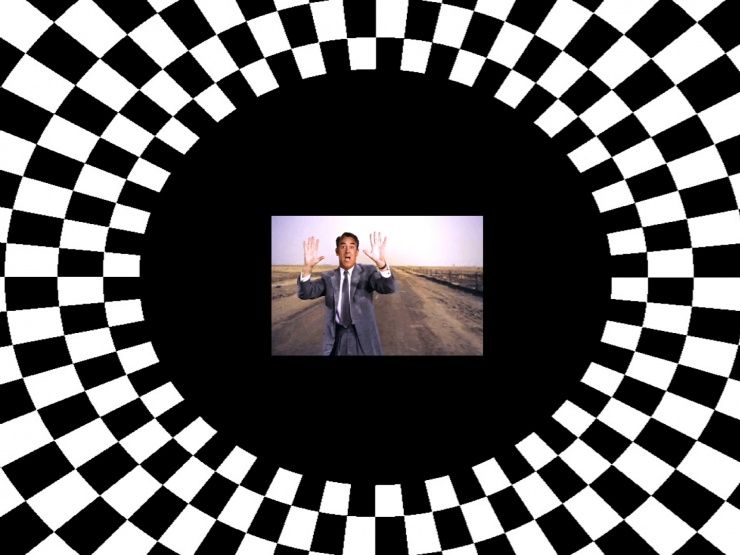

In the study, 19 college students were given functional MRI scans while they watched excerpts from 10 horror or suspense films, including Hitchcock’s North By Northwest and The Man Who Knew Too Much.

The movie played in the center of the screen while a checkerboard pattern flashed around it. The pattern was meant to serve as a distraction for the part of the brain called the calcarine sulcus, which often is attracted to and processes visual information similar to the checkerboard. Researchers collected data on which parts of the brain were activated as the movies’ intensities rose and fell.

They found that during the most intense parts of the scene, the brain blocks out the distraction of the checkerboard and focuses almost entirely on the movie. In other words, people become so fixated on horror films that their brains stop recognizing much else.

Then, when the movie scene lets up, the brain begins to relax and the calcarine sulcus starts to process the checkerboard pattern and its surroundings again.

Because our brain is so focused, we remember what we watched long after the movie ends.

That’s the part that always gets family science major Rawan Bannourah.

“Throughout the day I’m fine, but especially when I’m alone at night, I start thinking about it again,” the senior said. “I try to watch something funny before bed, but that usually doesn’t help.”

Doctoral student and film instructor Steve Beaulieu says Hitchcock’s movies remain some of the most popular and frightening because they’re so good at drawing you in.

“If you lose yourself in a horror film, you are a potential victim,” he said. “If that’s the sense that you get from it, then I think it’s absolutely successful.”

Beaulieu said Hitchcock uses a sense of voyeurism to make the audience complacent, then strikes with a big surprise. The special circumstances under which Psycho was released made the film that much more captivating.

“You couldn’t tell other people what happens because of the huge twist; you had to be there on time; you couldn’t leave the theater or walk in late,” he said. “That was a new theatergoing experience.”

Like the demons they sometimes feature, horror movies follow us. Science shows that because our brains are so engaged, we cannot escape the scary thoughts that follow us long after the film is over.

The thrill of movies like Psycho is that danger could be anywhere, especially in the shower.