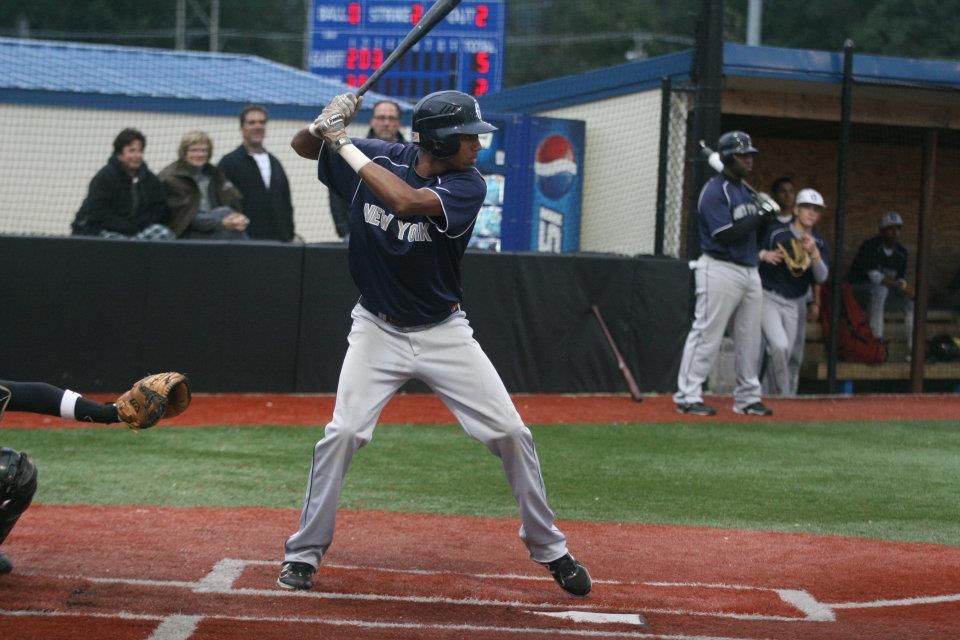

One is a lanky third baseman with dangling arms and a fluid running stride. The other is a stocky catcher who frequently hurls the baseball at the infield turf in excitement.

Despite their different physiques and personas, the lifelong friends and Terrapin baseball starters share the same story.

Third baseman Jose Cuas and catcher Kevin Martir grew up in East New York, once dubbed New York City’s “killing fields.” Baseball was their lifeline out.

It took the two kids from Brooklyn all over the country. When they were young, they traveled to Disney World for a tournament. As they got older, they spent most of their summers on the road and barely saw their parents. A coach, David Owens, became their father figure for those months.

“Without him, I don’t know what I’d be doing right now — probably, like, working at a grocery store or something crazy,” Martir said. “He helped me keep my head on straight, and he told me what was right, what to do and what not to do off and on the field.”

Baseball gave Cuas the opportunity to attend this university. His parents couldn’t afford it without the financial aid.

There were obstacles along the way. Sometimes, Cuas and Martir failed to steer clear of trouble, but days on the diamond gave them a reason to try.

“I feel like baseball was the path to a straight line, staying out of trouble and following the right footsteps,” Cuas said. “Without baseball, I don’t know where I’d be, but I’m glad I had it.”

CUAS

GROWING UP

They are teammates and best friends now, but Cuas and Martir first met as opponents.

When they were 6 years old, Cuas and Martir played against each other in a small local league called La Nueva Creda. While the league was for 6-, 7- and 8-year-olds, Martir and Cuas were the best players from the beginning.

They pitched to each other and hit home runs off each other. Out of that on-the-field rivalry, a lasting friendship blossomed.

“Our parents played softball together,” Martir said. “We’d always see each other at the park and just play catch.”

At 10, Cuas and Martir became teammates.

But their friendship, on and off the field, reached new heights when they joined the New York Grays and developed a special connection.

The two locked eyes across the diamond. Behind the plate, Martir nodded his head. At shortstop, Cuas touched his cap. No words were exchanged.

Seconds later, Martir fired the ball to second and Cuas applied the tag as the duo picked off another runner.

The scene played out numerous times during their time with the Grays.

“I don’t know if it was ESP,” said Owens, director of operations for the Grays. “They would just have this communication, and they would pick off so many people.”

‘ACADEMICS FIRST’

In the basement of a middle-school gym in Queens, a group of teenage boys gathered around their new coach, Owens. It was January 2010, and a few months earlier, the Grays had taken control of Cuas and Martir’s team.

Every player arrived early for the 8 a.m. meeting. While Owens was impressed by the squad’s punctuality, Martir’s appearance took him aback.

Martir, then a high-school sophomore, had braids down his back and wore his pants at his knees.

“If there’s a poster child for East New York, Kevin Martir was the person,” Owens said. “My first words to him were, ‘That’s not going to work in the real world.’ I started to curse: ‘Cut your f—— hair and let’s start acting like a professional baseball player.’”

While Martir initially chafed at Owens’ commands, he eventually relented. A new perspective helped.

For the first three years of high school, Martir attended a private school, Xaverian, before transferring to Grand Street Campus, where Cuas starred. The different environment helped Martir understand where Owens was coming from.

“What he was saying was right, and it’s gotten me to where I am today,” Martir said. “I’m very thankful for him.”

Before Martir met Owens, he never considered playing college baseball. His dream was to sign a professional contract out of high school.

Owens stressed the importance of education, though, and outlined the pros and cons of playing professional versus going to college. He taught his team about NCAA eligibility requirements, too.

At the time, Martir’s grades were poor and at the rate he was going, he wouldn’t be eligible for college.

“He was getting into trouble,” Owens said. “A lot of boys were getting into trouble. They weren’t taking school seriously, and basically I told them, ‘If you’re going to play in my program, it has to be academics first.’”

MARTIR

ACTING UP

Like most teenagers, Martir and Cuas just wanted to fit in.

Unfortunately for Martir, that meant hanging out with kids who skipped class and threw firecrackers in the hallway. Martir often got in trouble for fighting, and his mother regularly came to the principal’s office.

“I would get in a bunch of trouble,” Martir said. “That kind of changed [under Owens].”

Cuas attended a different middle school, one in Queens, where his mother worked. But the same problems existed there.

“It was probably one of the worst schools, academic-wise,” Cuas said. “A lot of gang activity going on and at such a young age.”

Every Friday after school, a crowd gathered and fights broke out. While Cuas didn’t fight, he’d follow his friends to watch.

“I needed the reality check,” Cuas said. “I got it junior year of high school.”

HIGH SCHOOL BLUES

At Grand Street Campus, friends encouraged Cuas to cut class every day. There were always parties to go to or opportunities to walk around off the campus. Sometimes, they’d simply go home.

It got to a point where he was suspended for a game his junior season. When his parents found out, a sit-down ensued.

“It’s your dream to play college baseball,” Cuas’ parents told him. “You’re going the wrong way. The way you’re going, you’re going to end up, God forbid, in prison or dead.”

Cuas’ father, also named Jose, threatened to pull the high-school star out of baseball altogether.

“It could have easily done a 360 turn,” Cuas said. “I could have easily been in a different situation than I am right now.”

After that talk, Cuas steered clear of trouble and the conversation transitioned to which college he would attend.

‘LET’S JUST DO IT’

Cuas’ cellphone rang like clockwork every day during his junior year.

When Cuas picked up the phone, Martir would be on the other end. And Martir asked the same question each time.

“Hey are you going to do it?”

Martir wanted Cuas to sign with the Terps. The duo had talked about playing together in College Park since the Terps started recruiting them as sophomores.

The day Martir committed, he told Cuas. Initially, Cuas was reluctant to sign. He had offers from Miami and Florida State, two perennial powerhouses. But Martir’s persistence paid off.

“You know what, let’s just do it,” Cuas recalls saying. “I mean, we have a dynasty together, and I want to keep going.”

But another option emerged for Cuas the summer before college.

PROFESSIONAL ASPIRATIONS

Cuas had a taste of the big-league life for one day.

The summer before his first year of college, the Toronto Blue Jays drafted Cuas in the 40th round of the MLB draft. The Blue Jays flew him to Toronto, and he took batting practice with the team.

“All the guys on the Blue Jays were like, ‘Come on, come on, sign,’” Owens said. “‘You’ll love it here.’”

Cuas wanted a $500,000 signing bonus, a figure usually reserved for higher draft picks. And the Blue Jays came close to that figure, Cuas said, which left him at a crossroads.

But Cuas couldn’t delay the decision forever. It was a Sunday, and the next day there was a summer program he had to attend if he planned on playing for the Terps.

So he sat down with his parents and adviser and made his choice. He was in College Park the next day.

“My parents were pushing for education,” Cuas said. “That’s important for them, for me to get an education and earn my degree. I don’t regret it.”

Owens was ecstatic. He wants all his players to attend college. Plus, Cuas and Martir need to mature, Owens said, and college is the perfect place for that.

“I wish all the kids out of New York City would be smart enough to do that,” Owens said. “It helped that they were together.”

‘EVERYONE’S REALLY NICE HERE’

In his hometown, Martir hears a constant refrain:

“What the hell you staring at?”

But in College Park, people are friendlier.

“Everyone’s really nice here,” Martir said. “It’s much different.”

Since they arrived on the campus in the fall of 2012, Cuas and Martir have played a major role in reviving the Terps’ once-dormant program. They started as freshmen in coach John Szefc’s first season. Then last year, they helped the Terps make the NCAA tournament for the first time in 43 years and advance to the Super Regionals for the first time in program history. Along the way, Martir and Cuas earned All-Regional honors.

“It’s great to see those guys thrive under Coach Szefc and evolve into two of the best players in the conference, which they are today,” said former Terps coach Erik Bakich, who recruited the pair,

Off the field, Martir and Cuas leaned on each other as they adjusted to a new atmosphere. They were roommates freshman year. They split up as sophomores, but Cuas is always in Martir’s room. The two play video games such as Call of Duty together.

“They’ve done a good job of navigating their way around campus,” Szefc said. “They’ve kind of learned how to adjust from the academic atmosphere they came from.”

Martir still calls Cuas “Chello,” a childhood nickname, even though the rest of the Terps usually refer to him as Jose.

“If he calls me Jose I won’t respond,” Cuas said. “I’m not used to hearing that from him.”

LOOKING AHEAD

Next year, Cuas and Martir might not be teammates. Both are eligible for the MLB Draft this June, and it’s unlikely the same team will select both Brooklyn products. Plus, one could turn professional and the other might stay with the Terps.

But Cuas and Martir are hopeful they can extend their years together as teammates.

“Someone might like us enough to take both of us together,” Cuas said. “There’s a chance.”

Right now, they want to savor their junior seasons. They’ve come a long way from the playgrounds of Brooklyn to College Park. There were plenty of roadblocks along the way.

But they emerged unscathed from East New York, largely thanks to the sport they grew up playing together.

“They made it out,” Owens said. “They enjoyed playing baseball enough to keep them out of trouble, and they finished high school. And you see where they’re at right now. They have the option that they don’t have to go back there if they don’t want to.”