Check out our multimedia edition for additional photos, audio and more.

IT’S BEEN 50 YEARS, but the events of Nov. 22, 1963, are still perfectly clear.

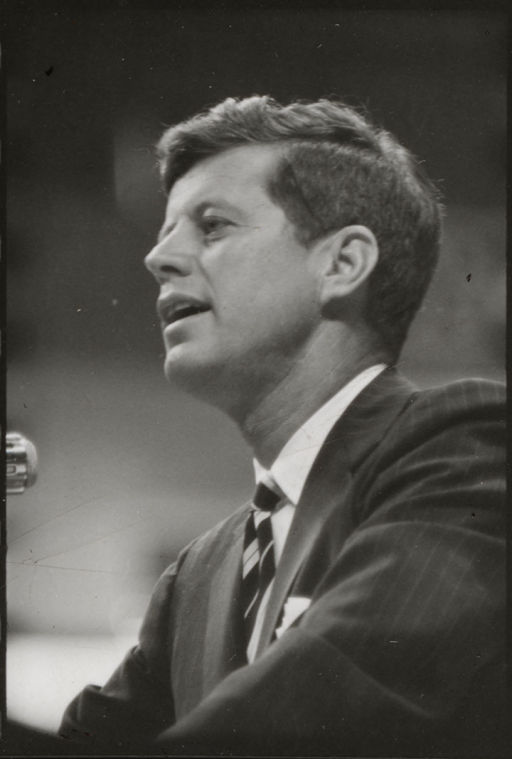

President John F. Kennedy touched down in Dallas as part of a Texas tour. Shortly after his arrival, he rode through the streets in his motorcade with the top down on his Lincoln.

His wife, Jackie Kennedy, dressed in the now-iconic raspberry-colored suit, sat to his left and then-Texas Gov. John Connally Jr. sat in the front seat of the car. Citizens waved and screamed as the motorcade made its 10-mile trek through the city.

Suddenly, there were shots. John Kennedy’s head exploded, and his wife — normally poised and chic — lunged over the back of the car to pick up the pieces of her husband’s brain or skull before he ultimately died. Connally took a shot to the back but survived.

Even 50 years later, it’s a haunting image seared into America’s mind. And to some, the details behind who murdered Kennedy are still murky.

“Kennedy’s been frozen in time,” said Keith Olson, a history professor specializing in 20th century American history. “It was such a shock to think our president could be assassinated.”

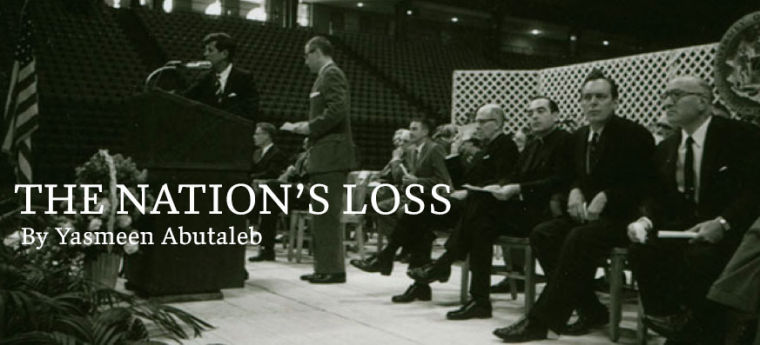

Kennedy had been no stranger to this university. While a senator, he spoke at the 1959 spring graduation and visited again in May 1960 while he was running for president.

Nov. 22, 1963, was the day conspiracy theories about who really killed the president began. It was the day citizens lost a charismatic leader they felt they knew and loved. And it was the day many Americans lost faith in humanity.

“The impact of President Kennedy was his personal dynamism,” said Fred Kahn, a university alumnus who said he helped start the Kennedy-Nixon presidential debates through letter-writing campaigns while he was a student. “It may be the reason he is still remembered by not only people who were alive then, but even those who learned about him.”

MAJOR NEWS NETWORKS had their local affiliates on the ground in Dallas. Kennedy’s Texas tour wasn’t a major news event — it was mainly to improve his image in the conservative state and rally support for the 1964 presidential election.

But at 12:30 p.m., Dallas became the crime scene that changed the nation. A bullet ripped through Kennedy’s head and another through Connally’s chest.

The cars carrying the political dignitaries sped off toward Dallas’ Parkland Memorial Hospital. The once-gleeful crowd quickly dispersed as people screamed and ran away, unable to comprehend the horror of what had just happened.

Then-university students Paul Palmer and Bill Seaby, staffers at campus radio station WMUC, were in a radio-announcing class when the classroom door flew open and another student yelled, “The president’s been shot!” according to a 2012 account from then-WMUC staffer Alan Batten in the University Archives.

As national broadcasters interrupted regular programming to report the news, Seaby and Batten kept a running on-air commentary of the unfolding events for the university community.

Wherever there were radios, there were students. They sat silently in disbelief in dorms, on McKeldin Mall, in classrooms and near the student union, according to a Nov. 26, 1963, Diamondback article, as reporters on the campus and across the country scrambled to deliver the news and make sense of it themselves.

By 3 p.m., another news bulletin had come in: Kennedy, just 46 years old, was dead.

“There was none of the between-classes chatter that is especially lively on a Friday afternoon,” The Diamondback’s story read. “This disbelief of the news did not lend itself to words.”

WMUC played “The Star-Spangled Banner,” unsure of what else to do. Then-university President Wilson Elkins prepared a campuswide address he delivered later that day.

“The tragic death of President Kennedy has affected people all over the world. This is the case because he was truly a citizen of the world,” Elkins said, according to an original copy of his speech in the University Archives. “The world has lost a great man, and American education has lost a dedicated friend.”

Before America had time to process the news, Kennedy’s vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, took the oath of office and became the nation’s 36th president. Jackie Kennedy stood beside Johnson with her husband’s blood spattered all over her stockings.

“I feel like part of my life was just taken from me. I feel an isolated emptiness I can’t describe,” student Gini Hinken wrote in a Nov. 26, 1963, letter to the editor in The Diamondback.“I feel that I would take the life of his murderer if I knew who he was. I have never wanted to kill or harm anything before in my life.”

BEFORE THE ASSASSINATION, Olson said, the 1960s seemed to be a golden age of sorts. After all, Kennedy had promised as much.

He would put a man on the moon. He would fight for civil rights. And he vowed he would do everything in his power to bring hope, peace and freedom to every citizen.

In less than two hours, that was all ripped away.

America’s president was shot and killed. Police identified the assassin. And a new administration led by Johnson was sworn in on the same Air Force One plane that carried the former president’s body.

For four days, from the first bullet to the funeral, the coverage was nonstop. Americans were glued to their radios and television sets.

First, there was the arrest of the assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, a 24-year-old who once defected to the Soviet Union. He shot and killed a police officer shortly after killing the president before police arrested him in a movie theater.

Then there were the questions, many of which still haven’t been answered.

Why did this happen? Was there more than one gunman? Were others involved? What does this mean for the country’s future?

Before Oswald had a chance to answer some of those questions, though, nightclub owner Jack Ruby shot and killed him on Nov. 24 as police guards led Oswald to a more secure prison.

Americans witnessed two assassinations in three days. The next day, they mourned through the funeral of their youngest elected president.

Schools and offices across the country closed on Monday, Nov. 25, including this university, which suspended classes for the first time in at least 15 years. Everyone needed time to comprehend the four days’ worth of events.

“The moment the nation’s loss is realized is when it awakes and discovers that the name that had grown so familiar is no longer heard; that a different accent has replaced one so well known; that friends and neighbors just don’t seem to talk about anything else,” The Diamondback’s editorial board wrote on Nov. 26, 1963. “It is this moment that the nation realizes it has lost a President.”

IF IT ISN’T CLEAR by the number of books or by the TV specials, series and movies that continue to focus on the events of Nov. 22, 1963, then it’s certainly clear by the number of Americans still wondering just how they lost Kennedy. A commission Johnson formed a week after Kennedy’s death, unofficially called the Warren Commission, investigated Kennedy’s assassination. It concluded that Oswald acted alone, but the group’s findings remain controversial.

A Gallup poll released earlier this week shows more than 60 percent of Americans still believe in a conspiracy theory behind Kennedy’s assassination. Five decades later, there are still lingering questions.

And that includes wondering what the country’s future would have been like if Kennedy finished his term.

“He did stir the imagination in a very positive way and the ’60s became much more violent after his assassination — the civil rights movement and Vietnam,” Olson said. “What if Kennedy had lived? … He didn’t have time to deliver. Maybe we wouldn’t have had some of those problems.”

John F. Kennedy speaks at University of Maryland convocation at Cole Field House.