For years, Noah’s Arc was a bold, blunt and melodramatic look at the lives of its predominantly gay black characters on the Logo channel. Yet director Patrik-Ian Polk (Licks) felt the need to take the series a step further by putting the crises and conflicts of screenwriter Noah (Darryl Stephens, Another Gay Movie) and his close-knit circle of fellow gay black men onto the silver screen.

“It’s an opportunity for us to take the show to a whole other level,” Polk explained in an interview with The Diamondback. “Even if you’ve never seen the show at all … you can still enjoy it.”

After watching Noah’s Arc: Jumping the Broom, however, one wonders who exactly Polk thinks will enjoy the movie. To put it simply, Arc is a gigantic, occasionally annoying and always cliché-addled mess.

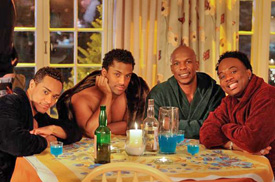

The film opens with a boat traveling to Martha’s Vineyard for the wedding of Wade (Jensen Atwood, Dante’s Cove) and Noah at Wade’s family vacation home. They are joined by a host of characters, all opposed to the marriage, who are saddled with their own predictable and ultimately tiring flaws and insecurities.

In charge of planning the wedding is the constantly screeching drama queen Alex (Rodney Chester, Shteps). Alex’s marriage with Trey (Gregory Kieth, Mistah Nice Guy) is hampered by his hysterics and the stress of taking care of their toddler, nicknamed OJ.

Ricky (Christian Vincent, Miss Congeniality 2: Armed and Fabulous) – the token “ho,” as he is labeled by his friends – brings along Brandon (Gary LeRoi Gray, Bring It On: All or Nothing) to serve as a consistent lay for the weekend.

Brandon has an awkward crush on his much older college professor, Chance (Douglas Spearman, Cradle 2 the Grave). Of course, Chance also has his own problems, such as a stale marriage with Eddie (Jonathan Julian, In Justice) and a preoccupation with writing his book.

Still, Polk does not believe the sheer number of storylines or subplots will not be overwhelming to those who are unaccustomed to the television show.

“I think we’ve given everyone a way into the show,” said Polk. “We have a new character. A young character named Brandon kind of comes in and meets these characters for the first time. He’s sort of a way into the backstory we need to get across.”

Even if audiences can process the large amount of overwrought plot thrown at them in just the first act of the movie, the fact remains the film has major flaws.

Polk said he hopes the average audience member comes out thinking “this is not so different from my own life.” That wish, however, becomes increasingly ridiculous as the film progresses.

The plot developments are earnest attempts to show the universality of certain conflicts in all relationships, such as balancing work and family, choosing between freedom and commitment and countering the lack of passion in long-term relationships.

Instead, the increasingly preposterous twists and revelations (for example, Noah outing Wade to his parents, Ricky kissing Wade because he still loves Noah, a closeted British rapper named Baby Gat) come across as inadvertent parodies of heterosexual culture.

At one point, Alex exclaims, “This is not a soap opera,” not realizing how utterly ironic that line of dialogue is in a movie with such artificial developments. Wade’s mother goes from being a bigot to a supportive parent (no prodding necessary) in about 20 minutes, and Chance’s partner forgives him instantly for being unfaithful.

Polk defended his treatment of Wade’s mother’s homophobia.

“I think the black community specifically has gotten a bit of the bad rap in the press, especially for being more homophobic than other communities,” Polk said. “I find that to not be true from my experiences.”

Aside from plot and character issues, Arc is also technically deficient. It is difficult to determine what causes more annoyance: the perpetual disco beat running through every scene or the acoustic guitar popping up for the umpteenth time as a character cries or throws a fit.

In addition, Polk and cinematographer Christopher Porter seem not to have discovered that cameras can move. Generally, they set the camera on a table or near the actor’s face and simply cut back and forth. The production utterly lacks any semblance of skill or dexterity.

Polk maintains his characters do not devolve into overblown caricatures by the time the expected happy ending comes. Instead, he thinks they are accurate observations of black gay men.

“We’re not representing all black gay men, certainly; no one movie could do that,” Polk said. “But I personally know people like all of these characters absolutely. We are certainly portraying a portion of the black gay community.”

diversionsdbk@gmail.com