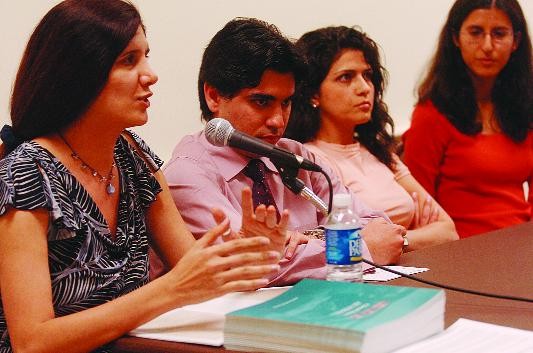

Parva Fattahai, Farshad Negarestan, Sahar Kasiri, and Pegah Parvini (left to right) spoke about being denied education in Iran.

When Sahar Kasiri applied to take entrance exams for state-recognized universities in Iran, she was faced with a difficult decision. There were four options to check for religion, and none of them were hers.

After being told she must pick one, Kasiri wrote in Bahai – the name of a growing minority religion not officially recognized by the Iranian government, which emphasizes the unity of all religions as messages from one all-powerful god. As a result, she was barred from taking the exam and, therefore, denied the opportunity to earn a recognized degree in her home country.

Kasiri, now a junior cell biology and molecular genetics major at the university, was one of four students who spoke last night at a panel about the Iranian government’s oppressive treatment of Bahais.

She – along with sophomore biochemistry major Farshad Negarestan, senior chemical engineering major Pegah Parvini and 2005 graduate Parva Fattahi – came to the United States to get official degrees after studying with the Bahai Institute of Higher Education, an underground school in Iran.

The problems in Iran began with a change in government in 1979, when the theocratic Islamic Republic of Iran was formed. When the new rule took over, Kasiri’s mother and aunt, who was 13 credits from a degree at an accredited university, were expelled because of their faith.

Fattahi said students could be enrolled in schools provided they did not identify themselves as Bahai. But Nadim van de Fliert, the Bahai Club’s secretary, said for a person of Bahai faith to identify themselves otherwise is equated to recanting their faith.

So they turned to the Bahai Institute, which was formed in 1987 and is funded by the Bahai community. Whereas most professors are not paid and see their work as a public service, there are still expenses such as lab equipment.

Without regular class sessions, most material had to be learned independently. The institute had a relay system that allowed the weekly homework assignments to be sent to professors. Students would get graded assignments and answered questions back in about two weeks.

Because the institute is not accredited, its degrees are not recognized and its credits do not transfer. Kasiri, who studied languages there, had 100 credits before she came to the United States, but none of them transferred, she said.

“This is all done because education is very important to us,” Fattahi said.

In Iran, Parvini studied science, one of the few majors offered at the Bahai Institute, with dreams of becoming a pharmacist.

“I wasn’t able to practice it, but I loved it – we all loved it,” she said.

Fattahi said she wants the right to an education there .

“All these years I was hoping for change,” she said.

Kasiri said her friends all felt sorry for her, but they couldn’t do anything because of the oppressive government.

“Perhaps one day others will be more familiar with our faith and the purpose of our faith,” Parvini said.

Contact reporter Damon Curry at currydbk@gmail.com.