In 1966, the NCAA Championship was played at Cole Field House, breaking racial barriers.

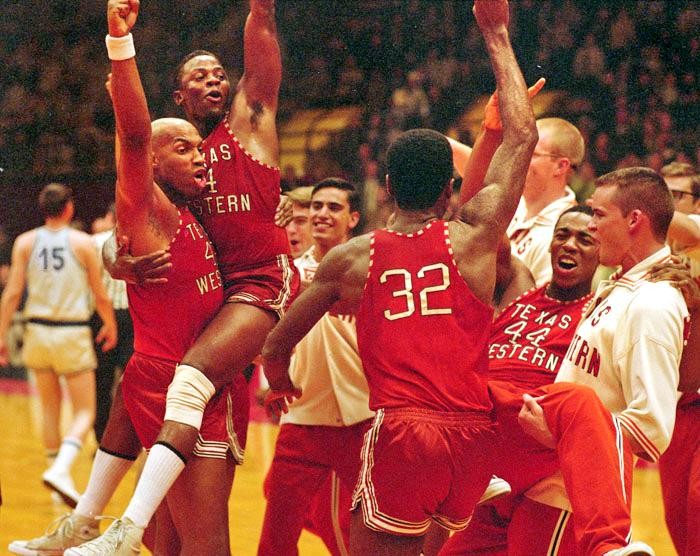

Nearly 40 years ago today, college basketball teams from Kentucky and Texas, one with mostly white players and the other with mostly black players, played a game that not only determined the national champion but also changed the way the nation viewed race.

What students learned when the game was recently made into a movie called Glory Road, which plays at Hoff Theater tonight, was that the game was actually played on this campus.

“I didn’t know that it was played at the Cole Field House until I saw the movie,” said Lamar Veal, a sophomore secondary education major who lists Glory Road as one of his favorite movies.

The fanfare leading up to the March 19, 1966 NCAA Championship game at Cole was minimal, according to university archivist Anne Turkos. However, after the game, when the all-black starting five of Texas Western defeated Kentucky’s all-white lineup, 72-65, the game took on enormous cultural significance for breaking racial boundaries during the civil-rights era.

“It was a landmark game in the history of college basketball,” Turkos said. “It’s very interesting to people that it happened at the University of Maryland.”

Many university students, including men’s basketball coach Gary Williams, attended the game out of curiosity.

“I snuck in,” Williams, a sophomore guard at the time, said to The Washington Post. “I was curious about Texas Western. Remember, nobody east of the Mississippi had any idea of what Texas Western looked like. There was no TV then where you could see them.”

The championship game was played during an era of racial tension. During the 1960s, many college basketball teams were mostly composed of white players.

“In fact, when I came to Maryland, I didn’t know Maryland and the ACC were all-white,” Williams said. “I grew up in southern Jersey. I had always played against black kids.”

Based on the book of the same name by Texas Western coach Don Haskins, Glory Road’s main focus is the racial discrimination Haskins’ team faced. At the time, southwestern schools were the last to integrate black and white students. Haskins’ revolutionary decision to start five black players was a first and provided the impetus for the movie, which has taken in $42.1 million to date.

“We found out that the final game was played at Cole Field House, so we decided to show the movie,” said Erin Gahagan, general manager of Hoff Theater. “We also haven’t show any sports movies this semester, and with the basketball season here, it was a good opportunity for us to show the movie.”

Veal said students should see the movie as a learning experience.

“It’s a real-life story and it gives people a chance to relate to what happened in the past,” Veal said. “It’s important for people to see it just so we can get an understanding of how far America has come as far as racism is concerned.”

Glory Road will be shown at the Hoff tonight at 7:00 p.m. and midnight, Saturday, March 11 at 9:30 p.m., Wednesday, March 15 at 7:30 p.m., and Thursday, March 16 at 5 p.m. and 9:30 p.m.

Contact reporter Jeremy Tam at newsdesk@dbk.umd.edu.