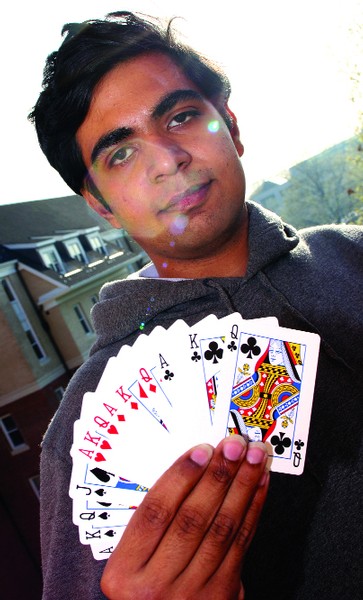

Junior computer science major Prahalad Rajkumar represented India at the junior world championships in bridge.

Fanning a hand of cards inches from his face, junior Prahalad Rajkumar glances across the table at his partner, who shows his full hand. His eyes dart from the table to his partner and then back to his own spread. He makes his move: Cards are flipped over, turned sideways and moved around.

This is the world of competitive card play, where passions run high and the appetite for outsmarting opponents can prove insatiable. But at last weekend’s tournament in Arlington, Va., the game of choice was not college poker favorite Texas Hold ’Em. This was the granddaddy of competitive card play — Contract Bridge and Rajkumar’s opponents are silver-haired and at least three times his age.

The game has recently experienced a comeback since its height of popularity in the 1950s, especially among soon-to-be retiring baby boomers who find themselves with more time on their hands. But a handful of college students, called “juniors” in tournament play, have also found their way into the game.

“Junior” or not, Rajkumar, 21, a bushy-haired computer science major, recently made waves on the national bridge scene. Rajkumar, who learned the game from his father as a child in India, reached the finals of the Life Master Pairs tournament in New York last July — the Super Bowl of bridge. He finished 32nd.

His passion for the game is clear. When he talks about it, his eyes light up, and he smiles widely. He chooses his sentences carefully, mindful that he’s talking to someone unfamiliar with the game and its quirks.

Although Rajkumar insists anyone can learn how to play — “All you need is to be able to count to 13” — he acknowledges the commitment needed to play well.

“It can take up to a month to learn,” he said. “Once you learn it, it’s a lot of fun.”

The game is played with four people paired off into teams that work to outfox each other. Older players are often drawn in by the social interaction, but with few young players, the American Contract Bridge League offers incentives such as scholarships and reduced fees to bring 20-somethings into the mix. For the top eight college bridge clubs, the league pays for airfare and accommodations in cities where national tournaments are held.

The ACBL has more than 4,000 members under age 25 and is working to add more.

“They are the future of the game,” said Linda Granell, the ACBL marketing director.

Though the university doesn’t have a bridge club, Rajkumar’s tournament partner is astronomy graduate student Michael Gill, who was drawn to the game’s competitive and mental aspects.

“Bridge is to hearts as chess is to checkers,” Gill said of its complexity. “Most people I’ve been around haven’t had the time to invest” in learning its nuances.

It hasn’t always been like this. Steve Robinson, a 1965 university graduate and Washington Bridge League treasurer, often played in the Student Union and said there were always 10 or 12 people dealing cards.

“I played bridge during the day and studied at night,” he said. It’s “an easy game to learn, but a hard game to play well,” which could frustrate younger players.

Noble Shore, a member of the ACBL junior team, said poker is young people’s competitive card game of choice because of the monetary rewards.

Most bridge players object to using money because it is one of the few competitive card games not associated with gambling.

For Rajkumar, money is nothing compared to the thrill he experienced at a New York tournament, where he faced former world champion Paul Soloway. Rajkumar engineered a ruthlessly crafty maneuver, which was “like re-raising in poker with nothing,” Soloway said. Soloway later told the Pittsburgh Daily Bulletin, a newsletter published during tournament play, that Rajkumar “earned his top.”

He isn’t stopping there. He relishes the idea of taking on the game’s best and aims to win a national or a world championship.

“If I were to win that, I would say that I had accomplished something,” he said.