Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

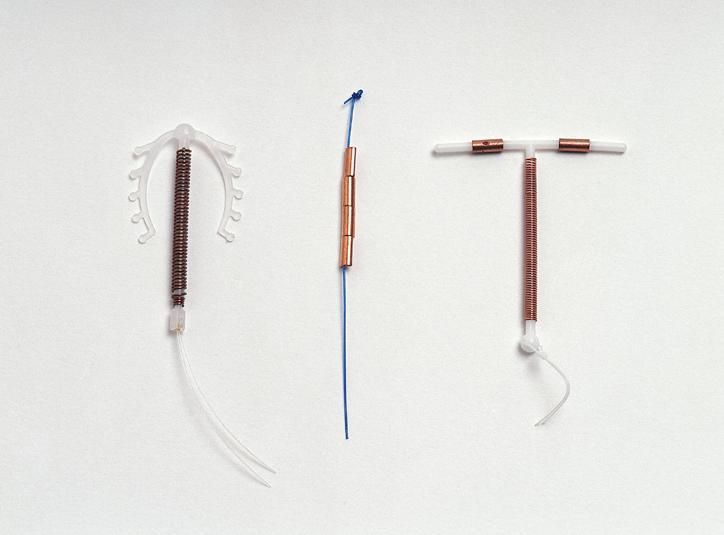

Birth control options have advanced considerably in recent years. Long term options have proliferated, with options including two types of intrauterine devices, an arm implant and a shot that all work to prevent pregnancy for between three months and 10 years depending on the method. However, only one of these options, the copper IUD known as ParaGard, does not employ hormones as a method of preventing pregnancy.

Hormonal pregnancy prevention can have side effects ranging from weight gain and acne to increased risk of depression. A 2018 study found that hormonal contraception use increased chances of being diagnosed with depression, which also correlated with an increase in issues with academic performance in college-aged users.

Despite recent developments in birth control technology, ParaGuard remains the only reversible, long term birth control option for people sensitive to hormones. Initially, the ParaGard seems like a saving grace. It can prevent pregnancy for up to 10 years with 99% efficacy and can be removed by a doctor at any time one may want to become pregnant, and insertion, while painful, takes only a couple minutes.

IUDs were released in the 1970s, but because they were seen as a medical device rather than a drug, they did not need FDA approval at the time, unlike other methods such as birth control pills. One brand of IUD in particular, the Dalkon Shield, was linked to pelvic inflammatory disease that caused the deaths of 18 people.

As a result, IUDs were largely taken off the market as they plummeted in popularity. Only recently have they experienced a resurgence in popularity as many fear the Trump administration’s impact on the availability of birth control. IUDs are the only form of reversible, long term birth control that could last up to ten years, longer than the presidential term limit.. However, they are still imperfect, as are all birth control options, given that they either incorporate the insertion of a foreign object into the body and sometimes the use of hormones, which interact with every body differently.

Birth control users are told to expect a litany of side effects from their birth control, and ParaGard’s begin with heavy cramping in the days following insertion to regularly heavier periods and worsened menstrual cramps. For some, however, the pain does not subside the week after insertion. A recent New York Times guest opinion columnist detailed her experience of the excruciating pain that ParaGard can cause, the disbelief expressed by many doctors at the extent of the pain, and the frustration felt by those for whom hormonal birth control is simply not an option.

Although we have a wider variety of birth control options than ever before, they all have one thing in common: People with uteruses are required to trade in some degree of daily comfort in exchange for reproductive liberation. Not only are they expected to be responsible for arranging methods of pregnancy prevention, they are charged with bearing the painful side effects.

Male contraceptive research has been largely left to governmental agencies as pharmaceutical companies found the pursuit to be less-than-profitable. Despite this, there are promising options being developed, but there are currently no options beyond the short-term use of condoms and the permanent option of a vasectomy.

Women, non-binary people, and men all deserve better. The entire premise of birth control is to prevent the interruption of daily life that unplanned pregnancy often brings. The options we currently have, however, do not guarantee an uninterrupted life, as contraceptive side effects can be debilitating. Pain should not be a necessary side effect in exchange for reproductive freedom.

Emily Maurer is a junior environmental policy major. She can be reached at emrosma@gmail.com.