To get a handle on the scale of deforestation around the globe, scientists use satellite imagery to provide a bird’s-eye view of forests on Earth. But current satellites can’t measure how tall those trees are, which presents an incomplete picture of the problem.

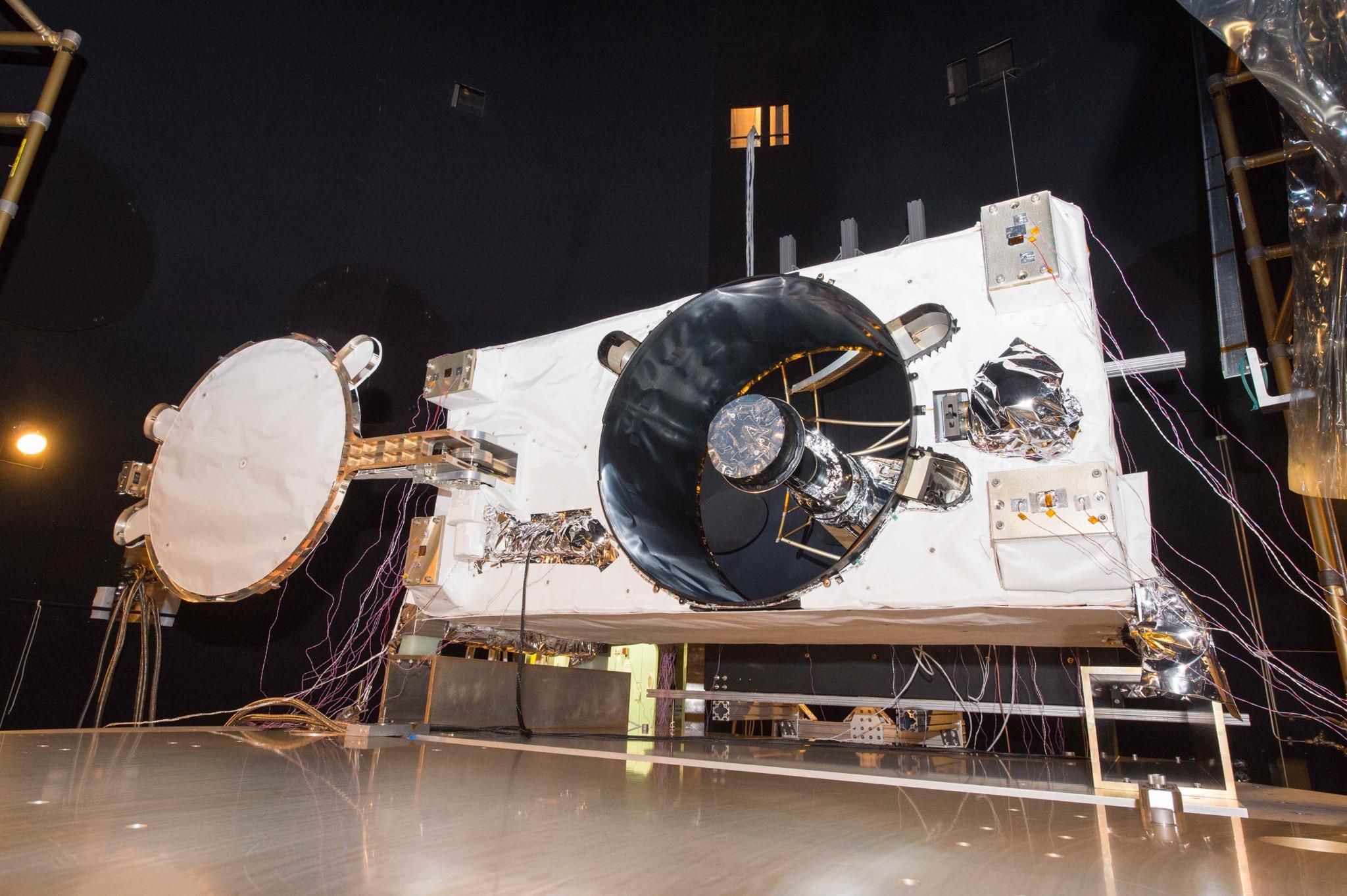

That’s where Ralph Dubayah’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation instrument comes in. Using lasers, the instrument can measure the height and weight of trees from space, giving more precise information on deforestation.

“We don’t know what the distribution of trees is throughout the planet — especially in the tropics,” said Dubayah, a geographical sciences professor at the University of Maryland. “When you look at them from regular satellite imagery, they all just look green. It’s providing this missing third dimension.”

GEDI — pronounced like the “Jedi” knights of “Star Wars” — was selected for development in 2014 after Dubayah submitted a proposal for it. This university has led the mission from beginning to end, in partnership with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Dubayah said.

The GEDI instrument arrived at Kennedy Space Center in Florida last week. It’s currently scheduled to launch up to the International Space Station on Dec. 4.

[Read more: Quantum computers aren’t practical yet — but this UMD-led team wants to change that]

Scientists are hoping that quantitative vertical figures will allow them to analyze forest heights globally, and by extension, how they affect carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere.

“We have equations that gauge trees’ weight from their height,” Dubayah said. “About half of a tree’s weight is carbon. So when trees are burned, that releases [carbon dioxide] into the atmosphere.”

Knowing trees’ heights will also allow scientists to “take a pretty good guess” on their age, Dubayah said. Trees’ carbon mass is derived largely from carbon in the atmosphere, and younger trees — which are still growing — pull more carbon from the atmosphere, whereas mature ones are in carbon balance.

Earlier this month, a report from a U.N. panel predicted that climate change would devastate the planet without drastic changes to the world economy in the coming decades. Dubayah highlighted the importance of having as much information as possible about the problem.

“In order to run any ecological model, we have to know what is going on right now,” he said. “That policy is all predicated on information about how much carbon younger trees will sequester from the atmosphere.”

[Read more: Should preschoolers take naps? These UMD researchers want to find out.]

The U.N. report spurred a group of 40 scientists to sign a statement pushing for the protection of forests across the world. More than 3 trillion tons of carbon dioxide are stored in the world’s forests, a greater amount than all readily exploitable reserves of coal, coal and natural gas, according to the statement.

Dubayah hopes the data will come to influence international environmental policy. For instance, when companies and countries know exactly how much carbon dioxide trees are pulling out of the atmosphere, they can know how many carbon offsets they need to buy.

GEDI is part of a NASA-run program called “Earth Venture,” which aims to launch missions that are smaller in scope on a more expedited framework, said Patrick Lynch, a spokesperson for Goddard. It’s unique in being the first laser observation instrument available from NASA or other countries in about 10 years, he said.

A sum of $94 million was allocated for the project, with most of the funds going to NASA for its construction and development. NASA project manager Jim Pontius was largely responsible for making sure the mission was developed at budget cost.

“Going to space is hard. Making lasers is hard. Making lasers in space is more than twice as hard,” Pontius said. “We’ve gone through a very rigorous qualification process.”

Among the challenges he faced was reducing the amount of cooling fluid the GEDI required to a level that the ISS would be able to supply.

Difficulties notwithstanding, Pontius said that “everything here is good as we could hope for. It’s a nominally perfect project as we could hope for.”

While GEDI is scheduled for launch in early December, Pontius said that may be delayed because two astronauts who were expected to form part of a five-person crew on the ISS had to abort a Russian Soyuz shuttle launch last week. GEDI’s payload is expected to be too much work for a three-person crew.

With the project’s finish line in sight, Dubayah remained cautiously optimistic.

“Everybody feels really good that we’ve gotten this far,” he said, “but there’s a lot of things that could still go wrong.”