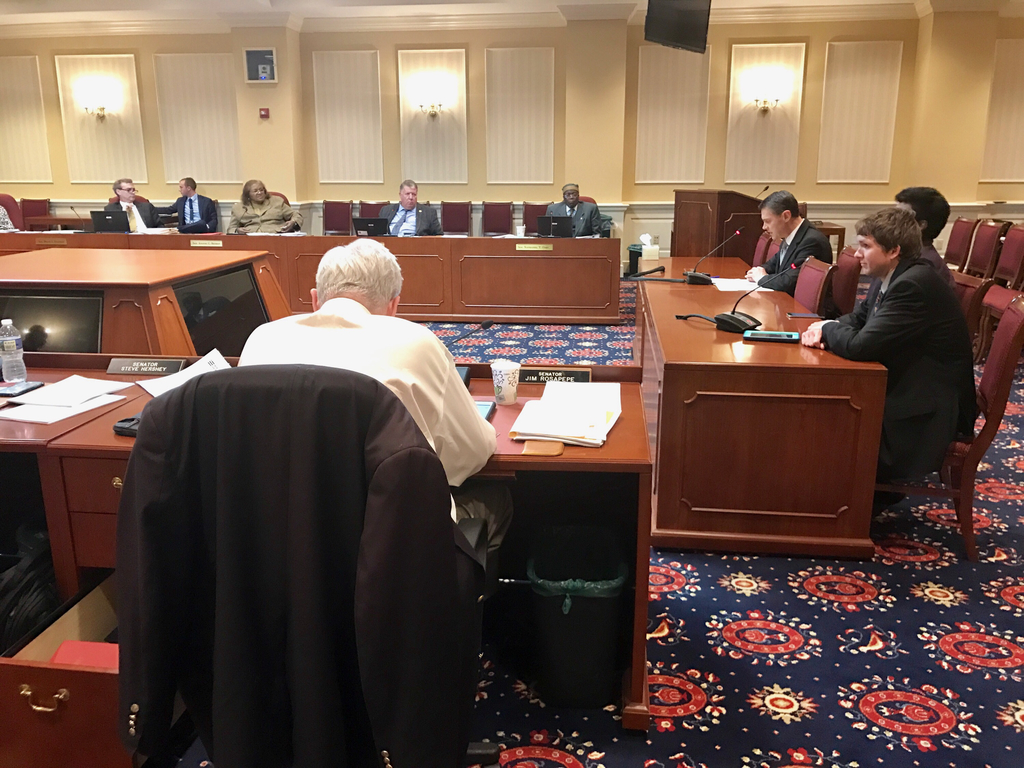

More than 100 University System of Maryland graduate students and faculty members submitted testimony for the state legislature’s Senate Finance Committee on Tuesday to support a bill that would grant graduate student employees at system institutions collective bargaining rights, and senators had mixed reactions to the bill.

The bill was heard in the House Appropriations Committee on Feb. 6, when 10 graduate students provided oral testimony and some 40 graduate students and faculty members submitted written testimony supporting it. The proposal would give collective bargaining rights to graduate student employees at the state’s public four-year colleges and universities, affecting the system’s 12 institutions, as well as Morgan State University and St. Mary’s College of Maryland.

The House and Senate committees where the bill is being debated will decide whether to send the bill to House and Senate floors.

[Read more: “We need this desperately”: grad teaching assistants could get collective bargaining rights]

While two graduate students testified at Tuesday’s hearing, about 30 students from this university, Bowie State University and Towson University drove to Annapolis to show their support for the bill, said Katie Brown, the Graduate Student Government public relations vice president.

“Because we don’t have mechanisms to get involved a lot of the time, the only way we can really show support is to show up,” Brown said.

Sen. James Rosapepe (D-Prince George’s and Anne Arundel), who said he has worked on issues related to collective bargaining rights for 30 years, said the presentation was “by far the best I’ve seen,” but that this “doesn’t mean it’s over the finish line.”

Graduate School Interim Dean Steve Fetter and a system representative also drove to Annapolis on Tuesday to testify against the bill, saying although the graduate school would like to increase the student workers’ stipends, doing so would restrict the number of assistantships the school could fund.

[Read more: A new collective bargaining bill excludes undergraduates. Many of them oppose it.]

Graduate Advisory Assistant Council President Will Howell was not surprised by Fetter’s appearance.

“It’s a good sign of how seriously the university is taking the need to reform — that they feel the need to fight it this much,” said Howell, a graduate assistants who provided oral testimony. “Clearly we’re doing something right that they feel the need to come out.”

After Howell testified, Sen. J.B. Jennings (R-Baltimore and Hartford) asked what benefits were afforded to graduate assistants apart from a stipend. When Howell said graduate student workers also receive tuition remission, Jennings sat back in his chair and said, “Wow.”

“Normally when people [ask for collective bargaining rights], they’re not getting compensated fairly,” he said. “I didn’t know you had [tuition remission] — that’s pretty big.”

While Howell acknowledged that graduate assistants are “very grateful” for the tuition remission, he added, “that’s money we don’t see. We still have to live on the salary we make.”

In written testimony, graduate assistants mentioned issues such as the need for affordable housing and the low stipend afforded to graduate student workers.

Enthnomusicology doctoral student Victor Hernandez-Sang wrote that the stipend he earns as a music school teaching assistant is not enough to support the costs of living in the D.C. metro area.

According to Hernandez-Sang’s 2017 earning statement, he took in about $12,592 last year after taxes and deductions. During his four years at this university, his parents have helped financially support him. An international student from the Dominican Republic, Hernandez-Sang holds an F1 visa, limiting his ability to hold an off-campus job, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

“The time I have to devote as a PhD student of ethnomusicology to my classes and assistantship duties leaves very little to no opportunity for me to teach private lessons on my own or perform independently getting paid under the table,” he wrote in his testimony. “I am constantly very constrained.”

While university President Wallace Loh recognizes graduate student workers face some “very legitimate issues,” he said the system is opposed to giving them collective bargaining rights.

“It’s a fundamental philosophical principle that [graduate student employees] are, first and foremost, students and not employees,” Loh said.

But Brown said this university profits from graduate student workers’ labor, and she does not think they are treated primarily as students.

“You can say we’re first and foremost students, but you employ 4,000 of us,” Brown said. “Grad assistants do the work of employees — we teach the classes, we write the curriculum. … We deserve the protections of every other employee on campus.”

If the bill passes, all graduate assistants within the system could negotiate wages and other terms of employment, something Brown said they are not able to do effectively.

Loh said graduate student employees already have a channel through which they can raise concerns with this university. Under meet-and-confer, which governs graduate assistants’ relationship with the administration, students can discuss job-related issues with the graduate school without any structured agreement.

Fetter said he is concerned about the welfare this university’s graduate students. Loh is committed to the success of the meet-and-confer process, Fetter said. But Brown disagreed, saying graduate students need a “legally enforceable mechanism to advocate for ourselves.”

Meet-and-confer “has shown me that when you have a system that relies on the good will of those in power and relies on administrators, grad assistants are always in a precarious position — they are always vulnerable,” she said.

CORRECTION: Due to an error, a previous version of this story incorrectly stated that this university employs 4,000 graduate students to teach classes. This figure also includes research assistants and other administrative assistants. This story has been updated.