I still remember how annoyed I was when my older brother interrupted my after-school Degrassi binge ritual to show me a new mixtape by some rapper under Lil Wayne’s wing. Like many other awkward sixth graders, I found solace watching Degrassi: The Next Generation on TeenNick. With disinterest, I listened to the surprisingly decent rhymes before glancing over at the music’s artwork. Lo and behold, it was Aubrey Graham — or Drake, as we now know him.

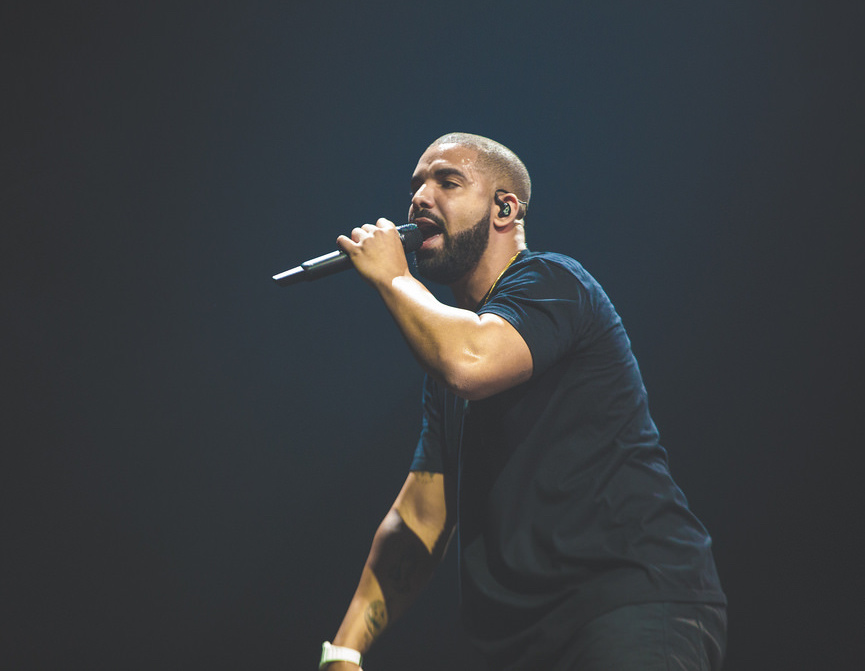

From his time playing a slick-talking, wheelchair-bound former basketball player on a teen drama to becoming an even cockier rap-star with his fair share of dramatic moments, Drake has played around with his voice. As More Life continues to rack up streams, the amount of credit the singer deserves for the coastal grooves on the album remains a hot topic for debate.

On Degrassi and in interviews, Graham speaks without inflection or poor grammar, while Drake raps with an unfamiliar accent, likely a reflection of the diverse city from which he hails. Drake has avoided criticism for his code-switching, as this linguistic process is common among leading black public figures, making accusations of inauthenticity expected and easily ignored.

Now, suddenly rapping with a Jamaican accent, the widely successful singer-rapper has received accusations of being a “culture vulture.” But like Post Malone and most other problematic artists show us, releasing “culturally responsible” hip-hop is ultimately irrelevant to predicting a rapper’s success. Drake’s past two musical projects, both heavily influenced by dancehall music, have been his most commercially successful releases to date. Both Views and More Life have broken music records despite drawing criticism in some social justice circles.

Most people would consider Drake’s identity as black, though he is the son of a Canadian mother and a black American father. Society, after all, largely still functions on the “one-drop rule,” which refers to society’s tendency to place mixed-race persons into an indiscriminate mass group. So, for example, any black ancestry, no matter how minimal, designates a person as black, point-blank. Perhaps unconsciously, race is compartmentalized into monolithic groups, erasing individual experiences. For black Americans who cannot trace their ancestry, sharing culture on the basis of shared complexion can provide a sense of identity to promote productivity.

Drake’s sudden embrace of Afro-Caribbean culture can be attributed to the idea of Pan-Africanism, which aims to solidify a robust base amongst the African diaspora. This movement, which grew in popularity in the 20th century, is attractive for those who cannot trace their ancestry due to slavery’s part in their genetic narrative. As J. Cole invokes in his music and tweets, his mother’s ethnicity does little to protect him from police brutality, as there is no uniform sense of blackness.

Drake’s creative combination of afrobeats and hip-hop rhythms is not a symptom of a musical identity crisis, but rather a desire to expose an inspiring subculture to a wider audience. Before imitating other dancehall artists like Beenie Man and Popcaan, Drake paid homage to the Caribbean culture through his social media. Before More Life dropped, the rapper cited influences for his new sound, while speaking about the changes in musical production in interviews.

As Drake garners criticism for banking on the mainstream music industry’s newfound interest in dancehall music, this label itself has turned into a blanket genre for music infused with afrobeats. Major Lazer already hopped on the bandwagon in 2015, receiving attention for creating unorthodox EDM on his 2015 smash single “Lean On,” which fused house music and reggaeton.

It’s not invalid for Afro-Caribbean people to feel frustration as they watch insular communities embrace their culture. But Drake’s respectful attempt to embrace African culture is not wrong at its core. His push for innovation, although mistaken for cultural appropriation by many, should receive celebration as anthems of African unity.