“Before you enter the photography galleries, walk five steps past them and look at this work by Vik Muniz,” said Sarah Greenough, National Gallery senior curator, referencing the large photo collage at a news preview Tuesday morning. “You can’t miss it.”

“He copied George Bellows’ 1911 painting of New York by tearing up magazines,” Greenough said. “It’s a very telling juxtaposition, I think.”

“Just as the Bellows painting, with its sea of humanity snarled in an impossible traffic jam … so perfectly represents the new New York that was emerging at the dawn of the 20th century, so too does the Muniz succinctly summarize the visual cacophony of the image-saturated 21st century,” she said.

The work alludes to the gallery’s collection of photographs, Greenough said, a collection celebrating its 25th anniversary of collecting photographs with this, the final of three exhibitions, set to open Nov. 1.

It’s a collection, she said, meant to “stand up to the finest paintings of the National Gallery and speak as compellingly about our time as those did to the moment that they were made.”

To the entire photography team: mission thoroughly accomplished.

NGA photog 2

The Muniz image, not a part of the exhibition but worthwhile on its own, is teeming with humanity. Bustling, buzzing, mad-dash humanity. So too do the works on view capture this intense corporeality.

The show turns photography’s scathing but unprejudiced eye on what Nietzsche and my art history professor would call “human — all too human.”

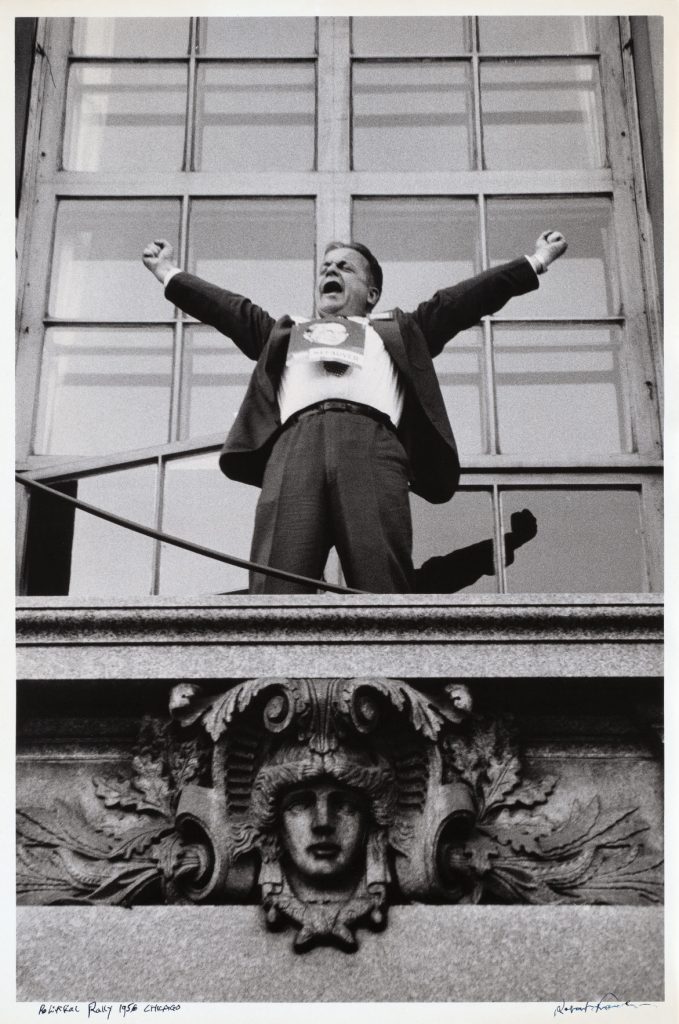

An early highlight is a set of images from Robert Frank’s The Americans that shows a country in flux from all the right angles. Richard Avedon’s The Family, occupying a wall across the room, faces off with The Americans to edifying results.

“Robert Frank and Richard Avedon, two giants of the postwar period … were very different artists from very different backgrounds with very different styles,” Greenough said. “And yet they each expressed the anxious tenor of the time.”

The Family was the product of a Rolling Stone commission on the power players of the 1976 election. There’s everyone from the disgraced — former Nixon Attorney General Richard Kleindienst — to the not-quite entirely risen — future President George H.W. Bush and future Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, among others.

Avedon’s pairings — retained from the magazine by the gallery — are entirely telling, from Senator Ted Kennedy and his mother Rose to César Chavez, the noted labor leader, and future President Ronald Reagan.

His most interesting and prescient dyad was of William Mark Felt, revealed in 2005 to be Watergate’s “Deep Throat” source, and Rose Mary Woods, President Nixon’s secretary. Other power players, including Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham, are portrayed with an affective intensity indicative of Avedon.

“Using his signature style,” Greenough said, “Avedon photographed his subjects close up facing forward, devoid of props and against a white background, almost like police mug shots.”

The prison theme is revisited quite literally by Deborah Luster in the next room.

“In the aftermath of her mother’s unsolved murder,” Greenough said, Luster “became fascinated with violence, crime and their effects on society. … She began to make portraits of inmates at several prisons in Louisiana, seeking to humanize them.”

“Titled One Big Self, it’s a disquieting reminder of the penal system and … the lives lost or put on hold inside and outside of prison,” Greenough said.

It humbly and sympathetically shows humans on the outskirts of society.

This outskirt, this space not quite without or within, is explored in the next gallery.

Continuing this and the prison theme is Lewis Baltz’s San Quentin Point series, part of a magnificent donation announced at the preview (the exhibition is entirely made up of new accessions).

The titular point is “a spit of land between affluent suburban homes and California’s oldest prison,” according to exhibition wall text.

Simon Norfolk’s famous images of Kenya’s vanishing Lewis Glacier chronicle another purgatorial place. “He plotted [the glacier’s] footprint in 1934, ’63, ’87 and 2014,” Greenough said. “With his camera set for an extended exposure, he photographed himself walking along those lines at night carrying a makeshift gasoline torch.”

“The resulting pictures capture the former boundaries of the glacier as a line of fire,” Greenough said.

The final room returns to humanity. Selections by Paul Graham interleaf a man ceaselessly pushing a lawnmower (like Sisyphus’s rock) with increasingly barren supermarket shelves.

A last work, like the cabin at the end of The Giver, provides a touching denouement on a quarter-century of collecting and nearly two centuries of photography itself.

It depicts Frank’s newly bought Nova Scotia cottage through four stitched photographs (one of which features the artist’s hand in a dominating foreground).

“By extending his hand over the landscape,” Greenough said, “he seems to be joyously inviting us to share this magnificent vista with him.”

In the show, we are similarly beckoned. So come and take a look.

“Celebrating Photography at the National Gallery of Art: Recent Gifts” runs until March 13, 2016.

“Mabou Mines” by Robert Frank depicts the artist’s newly-bought Nova Scotia cottage through four stitched photographs (one of which features the artist’s hand in a dominating foreground).

Robert Frank’s “The Americans” showed a country in flux from just the right angle, as here in “Political Rally — Chicago” from 1956.