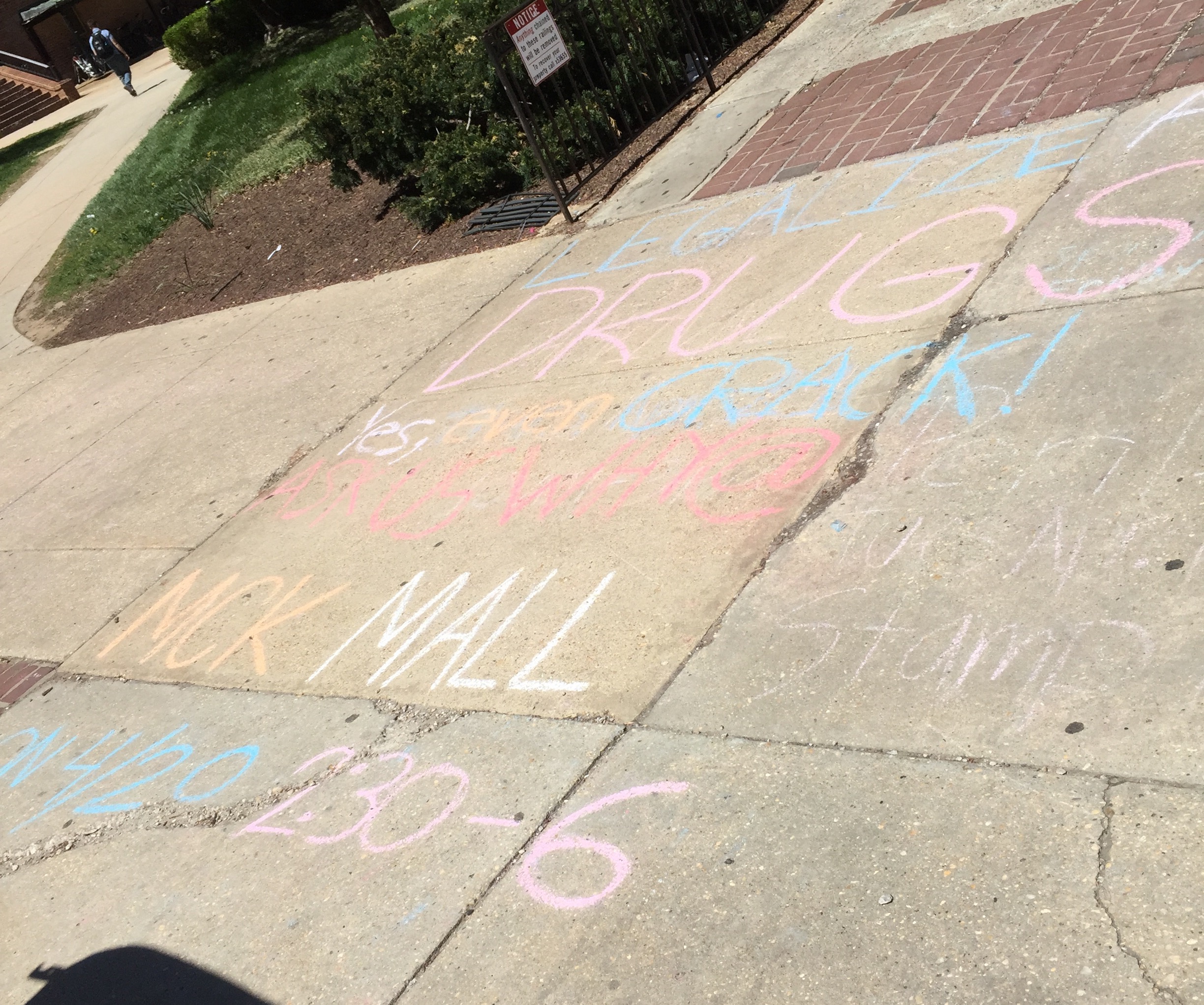

College is a great opportunity to meet new people and experience different ideas. However, many colleges restrict free speech. A recent example of this at the University of Maryland was observed on Wednesday when the campus staff washed away chalk messages on North Campus advocating for the legalization of all drugs — including crack — on the sidewalk in front of the entrance of the North Campus Dining Hall.

It’s not uncommon for university campuses to have policies that restrict free speech. According to The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, more than 55 percent of the 437 schools it surveyed have speech codes that significantly fail to meet First Amendment standards. These policies are evident even in this nation’s top universities. Harvard University prohibits “behavior evidently intended to dishonor such characteristics as race, gender, ethnic group, religious belief, or sexual orientation” and Princeton University prohibits verbal behavior “which demeans or injures another because of personal characteristics or beliefs or their expression.” Such policies are meant to protect students from harassment and discrimination, and for any university, these are legitimate concerns.

But while these policies are made with good intentions, they are not conducive to a learning environment, nor do they prepare students to confront opposing viewpoints in the real world. Differing opinions are meant to challenge current beliefs, which means they will inevitably be met with some discomfort. Being exposed to different beliefs expands our understanding of the controversy by opening our minds to different arguments or by strengthening our beliefs against the opposing perspective. If we adopt policies that prohibit speech just because they cause discomfort, we encourage a culture of blind obedience to the opinions of the majority, and outright dismissals to the ideas that are deemed harmful.

Herein lies the problem. People tend to think it is OK to limit basic rights if they believe doing so will benefit the greater good. But who is to determine what will benefit the greater good and how are we to believe they are trustworthy? We tend to accept the truthfulness of these decisions when they come from the majority or from sources of authority, but how can we know for sure that even they are right? There is no way to accept these decisions as truths with peace of mind except through proper discourse that respects all sides of the arguments.

Similarly, people only like to protect free speech when doing so advances their own social agendas. Universities do this when they prohibit speech that is discriminatory, or speech that advocates for things such as the legalization of drugs. This reminds me of a task that was given to my group during a University Student Judiciary interview last fall. As a group, we were to play the role of college admissions officers and select who to admit from a pool of hypothetical applicants, all with some sort of inappropriate behavior on their records. What was striking to me was that the interviewees in my group only admitted the students whose actions — some even with physical consequences — were for a cause they deemed worthy and denied admission to the ones whose disciplinary records were for unworthy causes such as making discriminatory remarks toward a teacher.

There is nothing wrong with respecting those who are willing to advocate for something they believe deeply in, but by this logic, we should not be judging based on the content of the speech. To restrict speech that opposes an entity of power’s own social agendas is very hypocritical and reminiscent of autocratic governments.

For an effective learning experience, we must be exposed to as many perspectives as possible, even the ones we may deem morally objectionable. It is for us to then differentiate between the right and the wrong, and it is never acceptable to deem a viewpoint correct only because it adheres to the opinion of the masses or a person of authority.

In order to facilitate this productive discourse, we should let everybody freely express their viewpoints on college campuses. It is also better we learn to resolve these issues instead of letting authority decide which side of the movement to quell.

William An is a freshman in the business school. He can be reached at willandbk@gmail.com.