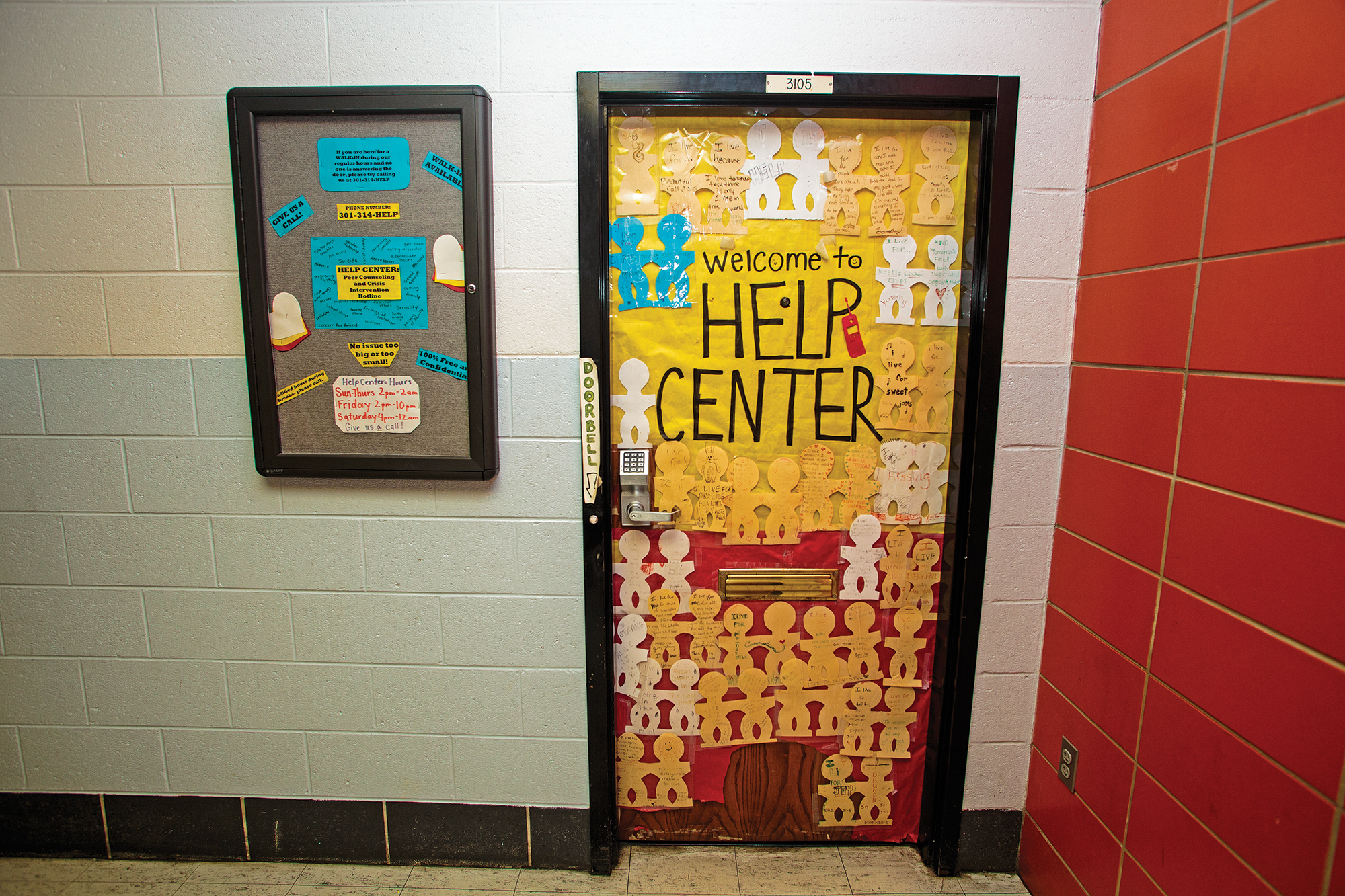

On the door there are people without faces. They are cutouts made of paper, taped to the wood in slightly overlapping pairs. Their rows cover most of the surface, save for a big square in the middle that reads “Help Center.” Each blank body is marked up with a different handwriting and each seems to be answering the same question: What do you live for?

“I live for every fall when the leaves change,” one reads.

“I live for kettle cooked chips,” says another.

“I live for every time my boyfriend calls me beautiful.”

“For brunch.”

“For kissing.”

“For drawing bunnies in my notebook.”

To get to the door, one must enter the South Campus Dining Hall and take the stairs. Head down a wide hallway littered with abandoned chairs, past the office offering help with student legal aid, past the activist headquarters, past the newspaper newsroom, past the sign that says “Senior Photos” with an arrow and past the bulletin board with the flier asking you to “say no to the corporate deathburger” that features a large picture of what looks to be a Big Mac. Make it through all that, and you arrive at a quiet corner and the door with its coded lock, its doorbell and its reasons for existing.

Behind the door is this university’s Help Center. Run entirely by student volunteers, it is one of the most immediately available mental health resources on the campus. With its doorbell available to walk-ins and a hotline number posted all over the campus, the Help Center offers an alternative to university options that are overbooked, understaffed and unavailable for as much as several weeks to those who wouldn’t classify their situation as an emergency.

It’s no secret that this university has had its fair share of mental health-related events in recent years. Every day, on a campus of more than 37,000, people face emotions that are hard to combat alone. Right now, this door, this place, is the foremost hand being held out-. In the fight on this campus against the stigma of talking about how you feel and the fear that those feelings are anything other than normal, this is the front line.

***

Founded in 1970, the Help Center used to be located in an off-campus house that was open 24 hours a day. The problem became that people would show up at odd hours, often drunk, seeking a couch or maybe something to eat instead of psychological assistance. Now, having been above the dining hall since the late ’90s, the center is open between eight and 12 hours each day.

The current headquarters has big windows and several rooms. There’s the common area with its pamphlets and the staff lounge that has handprints on the wall from volunteers past and present. Across from that is the room where walk-ins can talk to someone. There is a small couch, a pile of books on a shelf and a pillow with raspberries on it. On the table is a box of pregnancy tests. In the corner, there is Guess Who?, a board game about trying to determine who someone is.

Tom Hausman/The Diamondback

The staff of volunteers number about 80, 50 or so of whom are currently active. Shifts last four hours and can be staffed by anywhere from one to seven people. A busy day would see 15 or more calls and maybe a walk-in. But someone must be in the final room of the Help Center, the call room, at all times. Access to the call room is forbidden to anyone not on staff. It’s supposed to be a haven for those people in it, a place where nothing else matters besides the voice on the other end of the line and the person sitting next to you.

“It’s a safe spot, kind of like your bedroom at home. You can focus and you know that you’re safe there,” said Help Center President Leah Sukri, a biology and psychology major. “The people in that room have shared experiences.”

Those people who take calls are called counselors. The process to become a counselor can take anywhere from two to four semesters and is so necessary to the organization that, of the active members, the trainee-to-counselor breakdown is close to 1-to-1.

And who are these students that want to join the Help Center, to volunteer their time, to sit by the phone or wait by the door? Well, you know that kid on your floor freshman year whom people felt like they could talk to? Who would sit cross-legged on their bed and listen as you fidgeted on the desk chair, hammering away at your schedule or your friends or the way things were? The one that would ask questions and talk and talk and talk if need be? Those kids? They work at the Help Center.

“Oh God, everyone here is so nice,” counselor Michelle Dagne said, laughing as though it were some kind of bizarre phenomenon.

“Surprisingly kind,” junior English and mathematics major Sam Cunningham, currently a trainee, said of his co-workers. “Everyone here, they’re all the kind of people who go way out of their way to be there for someone.”

They come not only from the social sciences but also a variety of majors and backgrounds. They are good speakers and even better listeners. But they are also students with schedules and stresses and worries, just like the person on the other end of the line.

“Maybe you pulled an all-nighter or maybe you have relationship issues and you come in and you pick up the phone, and that can be hard,” Dagne said. “Putting away everything else that’s going on in your life is hard.”

In order to be a Help Center employee, you have to learn how to make that happen, how to put someone else’s situation before yours, if only for a while. It can be a challenge, but every day it’s done, there in the haven or in the room with the couch and the raspberry pillow.

***

In the 20th century, before the advent of texting and chatting and direct messaging, there used to be something called a person-to-person call. It was when you asked the operator to put you in touch with someone specific. The term is antiquated now, but it in a way it captures what happens when someone calls the Help Center hotline. No names are exchanged. Just two people on the line, two voices taking turns. It’s not a call intended for a particular recipient, this person to person. It’s a call for someone, anyone, to answer.

And it can go on for as long as it needs to. One rule amongst counselors is that you never hang up the phone. Ever. The caller must be the one to hang up, and sometimes that takes a while. According to the volunteers, more calls tend to come in the afternoons. Sometimes the numbers go up at times when classes let out, people reaching out as they make their walk across campus.

The conversation isn’t designed to provide the caller with answers, and unlike professional help, it will never end in a label. Counselors say the idea is more to walk someone through something, to use listening as a tool.

“Sometimes just being made to string thoughts together in a coherent way, as we’re expected to in any conversation, can really help you to make a path through your situation,” junior psychology major Morgan Benner said. “We’re not there to take their feelings away over the phone, we’re there to share the burden with them.”

But sometimes sharing that burden can take its toll, especially considering the finite nature of a phone call.

“Working at Help Center requires a lot of self-care,” Benner said. “As a counselor, you handle a lot of situations where you don’t necessarily know whether you’ll be able to help them. People call and you can be there for them and talk them through things, but at the end of the day, they hang up and you don’t know whether it’s going to be OK.”

Sometimes after a shift, Dagne said she just needs to put on Netflix for a while and watch something light. It helps to clear the mind. She said she has gotten emotional after working before and that it was to be expected sometimes. It’s natural.

Benner said her experiences at the Help Center have changed the way she thinks about her surroundings.

“You end up having a rapport with someone on the phone, and you grow to care about their situation and you realize that it could be anyone walking around with you,” she said. “And you realize that all these people around you have these issues that they might want to talk about. Everyone has their own stuff that we have to deal with all the time. Sometimes it weighs on me that the people around me may not have someone to talk to about it.

“Everyone is just walking around. With their stuff. Carrying it around. That’s what weighs on me.”

***

Tom Hausman/The Diamondback

People come and stay in different ways. Sukri first heard about the Help Center from her freshman-year resident assistant. She joined that spring. Benner also joined the second semester of her freshman year. She says she did so because she enjoyed hearing people’s stories. Dagne came to this university as a biology major and changed to psychology in part because of her experience at the Help Center. For Cunningham, his majors remain English and mathematics, but the Help Center has had a different effect.

“It seems almost selfish because the whole motivation for being here is, of course, at the heart, selfless, but goddamn, you get a lot from it,” he said. “I wanted to do something in the technical fields, but now I want to go into mental health. There’s still so much to do; some stigma that needs to be broken down.”

It’s clear in talking with Help Center volunteers that the entire organization is dedicated to the external: anyone out there who needs them. But it’s also clear that the organization serves a purpose on many levels for those on the inside, too. Whether it provides career-oriented experience, a hobby to feel good about or just a group of like-minded friends, the center commands a devotion not found among many other student groups.

It’s that bond between students that remains the defining trait of the Help Center and sets it apart from the other mental health resources. The helping hand can be offered with such strength, such certainty, only because it has a body to support it.

“There’s not really going to be a point in my life where I don’t think about how much [Help Center] has affected me,” Cunningham said. “It has a blanket statement over my whole existence at this point that it’s changed me.”

***

In the past two fiscal years, funding directed toward student services — a category that contains the mental health offerings by this university’s Counseling Center and the University Health Center — decreased by $245,908. While mental health awareness has arguably gone up on the campus recently and administration is making efforts to keep that trend going, the school still faces logistical issues.

“Knowing that mental health resources are backed up on campus, I just wish we could do more,” Dagne said. “But you can’t make people call in.”

Help Center volunteers say that this fact — that any kind of help they can offer takes place in a process that can only begin one way — is something that must be accepted. All they can do is get the word out and let people know it’s OK to call, no matter what the issue. The line will be open.

“A lot of people think we’re only here for extreme situations, and that’s not true,” Benner said. “I would love people to know more about calling for maybe a roommate issue or maybe just something you don’t want to tell your friends.”

Added Sukri: “It’s something that has a stigma. Reaching out to someone can be a weird concept. But I think slowly that’s being chipped away.”

That might be true. But for now, the corner door is not overwhelmed with entrants. It is mostly volunteers punching the code, arriving just to be there. The door closes behind them, covered by the faceless people and their handwriting. Even though some of the marker has begun to fade and some of the tape peels, each one still touches another.