“Rock is dead,” Nietzsche said before lighting a blunt and turning on Future’s “Stick Talk.”

It’s 2016, and if rock isn’t already dead, it’s dying. This may be upsetting for some to hear: “How could that be,” they’ll ask, “when Green Day is set to release an album next month?”

But even an album with the rock as fuck title Revolution Radio (from a group of 40-year-old punk rockers, no less) can’t save a dying genre that’s rapidly being overtaken by the Biebses, and the Migoses and the Drakes of the music world.

Which seems incredibly strange, considering that 25 years ago, rock wasn’t just thriving, it was on the cusp of something great. For all the bad sitcoms and constant flannel-wearing, the ’90s proved to be a period of intense experimentation and splintering subgenres for rock music, the experiential college years of a genre generally confined by just six strings in standard tuning.

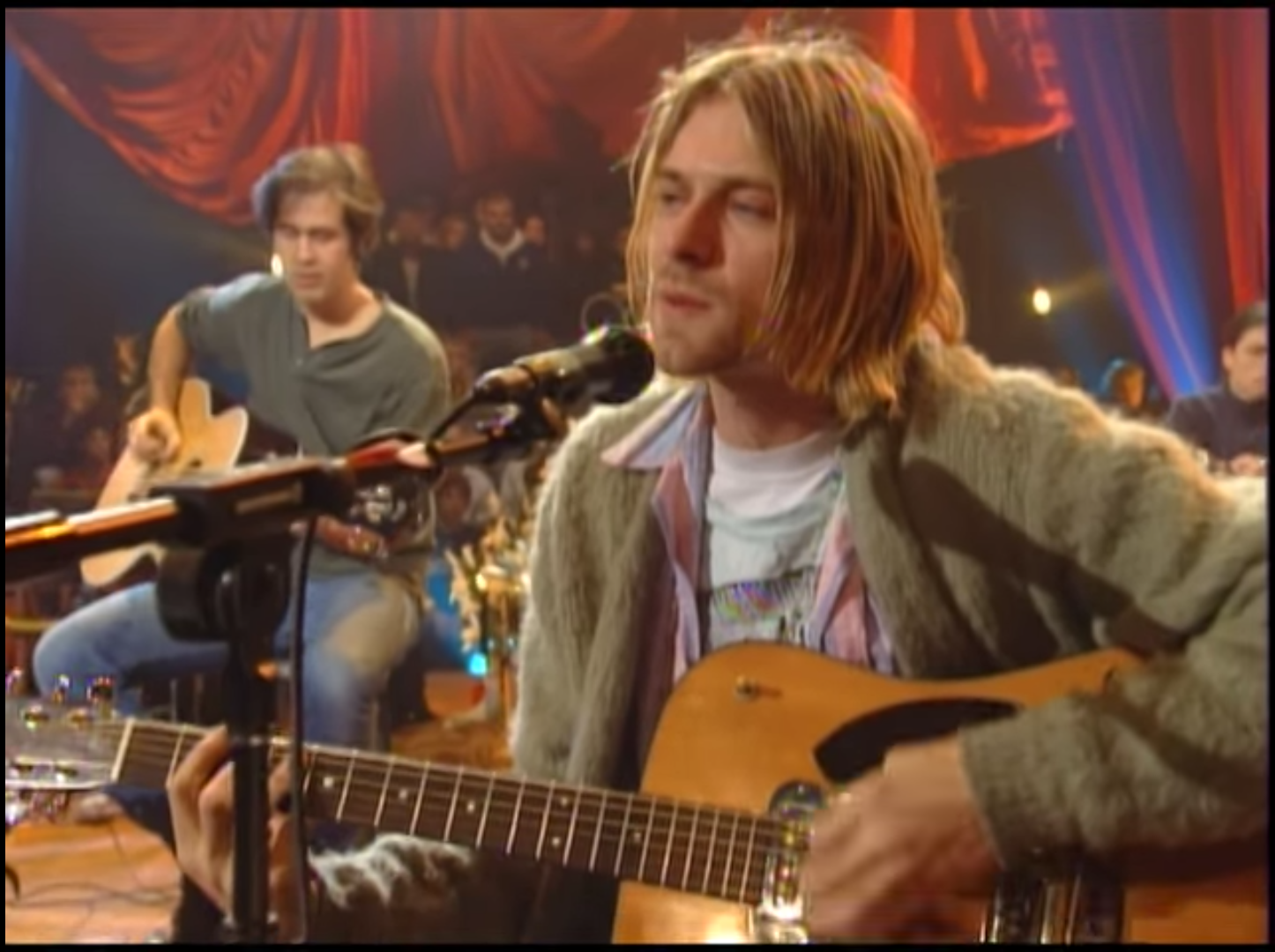

But it wasn’t the dicks-out funk punk of the Red Hot Chili Peppers or the gateway drug reggae rock of Sublime that stood as the Rock Gods’ greatest creation of the 90s — it was Kurt Cobain’s four-chord angst machine named Nirvana.

When the group’s breakthrough album Nevermind was released on Sept. 24, 1991 — 25 years ago on Saturday — it changed rock music. Not with impressive musicality or Broadway-inspired stage theatrics, but by taking the tight, catchy chords of pop music and blending them with Richter scale-worthy distortion and 24 years of depression.

Songs like “Lithium” and “Smells Like Teen Spirit” introduced mainstream audiences to the dark, sunglasses-at-night world of alternative rock simply by making songs catchy enough to sing along to. The record doesn’t compromise in any other way: The instrumentals are abrasive, the lyrics are dark and at times disturbing, and Cobain’s outlook on life is no less dreary. It’s a remarkable feat of musical chiaroscuro, reflected in structure, too. The quiet verse, loud chorus format of many of the album’s songs is a jarring showcase of Nirvana’s “one-foot-in-each-world” musical dichotomy.

Twenty-five years later, it’s a style that Nirvana still does better than anyone else. But even if rock’s most notable attempts at that blend of unforgiving gruffness and commercial polish ended in nu-metal and pop punk — both tragedies in their own right — it’s an idea that has left an impact on popular music as a whole.

Without including the weird, ugly poetry of “Drain You” or the hauntingly beautiful true-story narrative “Polly” on one of the most successful albums of the ’90s, it’s hard to imagine a music market as willing to accept the oddities that somehow sneak into the mainstream. Atlanta rapper Future often raps over chest-rattling trap beats, too menacing for pop radio, and touches on depression, drug addiction and violence in his music. But somehow, even his darkest tracks — “March Madness,” “Codeine Crazy” — get played at parties and concerts.

How? The same way that “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” a song boasting lyrics like “Load up on guns bring your friends/ It’s fun to lose and to pretend,” became, quite literally, the song of a generation. It’s catchy, it’s aggressive and it’s iconic — the type of track that should not work in as many ways as it does.

But that’s the power and impact of Nirvana’s Nevermind. For every mainstream hit still played at grunge-themed parties, there’s a “Territorial Pissings,” a feedback-ridden headbanger that’s as likely to make your mom sell your stereo as it is to get trapped in your head for all eternity. And at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter which: Both will burn the album into your mind.

As rock in the mainstream takes its final breaths — at least for now — Nevermind remains pretty much unchanged. Twenty-five years later, it’s still an uncompromising compromise of underground and popular, brutal and beautiful, sophisticated and simple.

And damn is it good.