The never-ending saga of Jussie Smollett’s potential, extremely confusing assault has been kind of exhausting. The sheer implications of his alleged actions — staging a racist, homophobic hate crime in order to profit or garner sympathy — are especially harrowing when you consider the boy-who-cried-wolf effect this could have on others in similar situations.

If what the Chicago Police Department claims about the situation is true, we are left with the fact that — in our extremely polarized political climate of fake news and hate crimes — a story that originally shocked the nation and mobilized some of its most powerful people to speak out has all turned out to be a hoax. But the collective reaction of many people and media outlets to Smollett’s situation (let’s not call it a crime until the investigation is concluded) is reflective of a larger, troubling cultural trend that dates back to antiquated and racist preconceptions of how we perceive people of color.

Maybe you’ve heard of a term called “minority exceptionalism,” similar to the model minority myth. The basic premise is we have much more acceptance for broad generalizations when we talk about minorities, and we view their actions as representative of an entire group. For example, there is a largely held stereotype about Asian Americans being the model minority because they are hard workers, very intelligent and work in STEM fields. While it is true that there are many exceptional Asian immigrants, the pressure from projecting this ideal onto an entire, very large group of people creates a narrative that robs them of their individuality.

Sure, it can be argued that it is a positive perception and should be embraced. However, it tells any Asian Americans who deviate from the norm that they are not exceptional, while also allowing racist comparisons between minority groups as if we are all competing for some grand prize of No. 1 non-white. Hasan Minhaj does a great job of explaining this.

[Read more: Why grouping Asian-Americans together makes individuals invisible]

When we observe the actions of a white American person, good or bad, they are afforded the luxury of autonomy; their actions are representative of them, and them only. Over half of the mass shootings in the U.S since 1982 have been carried out by white men, and yet there is no movement to discredit or marginalize all white men within our society. Time and time again, we are forced to witness the trope of the “lone wolf” within coverage of these tragedies, which provides overwhelming evidence of selective cultural awareness so as not to reduce a whole demographic to the actions of a select few.

If we take a step back and objectively view the accusations against Smollett, we can see his alleged behavior as an individual was wrong. That he may have strategically framed this crime in a way to perfectly fit our nation’s political unrest makes it even more uncomfortable to look back upon. There will surely be repercussions for others as a result of Smollett’s supposed selfishness. But amongst the outrage, let’s not kid ourselves and pretend that queer, black victims of hate crimes are paid much attention in our daily news anyway.

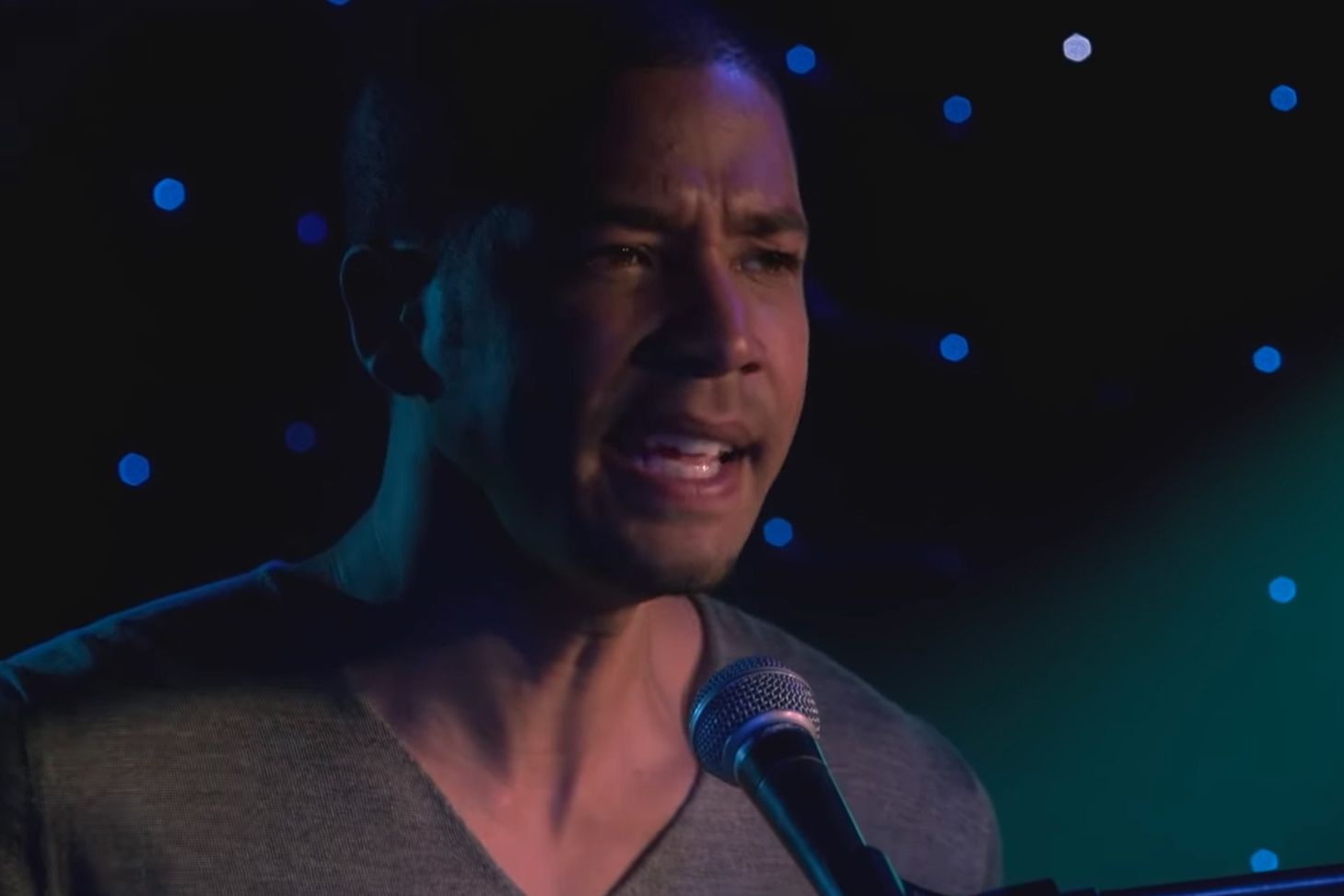

Smollett is now facing heavy criticism and disappointment from both sides of the political spectrum, but especially from the LBGTQ and black communities, because of how he is forced to represent both groups instead of just himself.

Cardi B claimed he “fucked up Black History Month,” and many other black celebrities and figures expressed reasonable frustration and disappointment in Smollett’s alleged actions. But this begs the questions: Did he hurt or kill anyone with his accused actions? If found guilty, will he pay for the police investigation out of pocket? Perhaps more importantly, why do so many other people who file false police reports in race-targeted attacks fail to face the same consequences and scrutiny?

[Read more: Does cancel culture have an expiration date?]

Smollett may have really messed up. But in a society that does not seem to hesitate to demonize black men and children — though arguably the latter is lumped into the first category all too often — it seems people have taken the opportunity to lash out at a young, queer black man and absolutely run with it.

This collective punishment forces people of color to always think three steps ahead in the ways they conduct themselves, raise their children and simply occupy space in a innately racist, unfair playing field. It is what forces young children to lose their innocence when they are taught they must always be aware of how their clothes, obedience of the law or existence are inherently loaded.

Smollett, if he did commit the crime, was caught red-handed in front of the entire world, and will pay the consequences through the legal system and the inevitable end of his acting career. Why should everyone else in his communities have to pay for it, too?