Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

I’m glad we’re all finally realizing college is a scam. The internet lit up Tuesday with news and commentary on the FBI investigation of celebrities accused of committing bribery and cheating to get their kids into selective colleges. The attention and outrage surrounding this scandal is well-deserved, but transactions involving large sums of private money between wealthy donors and universities are nothing new.

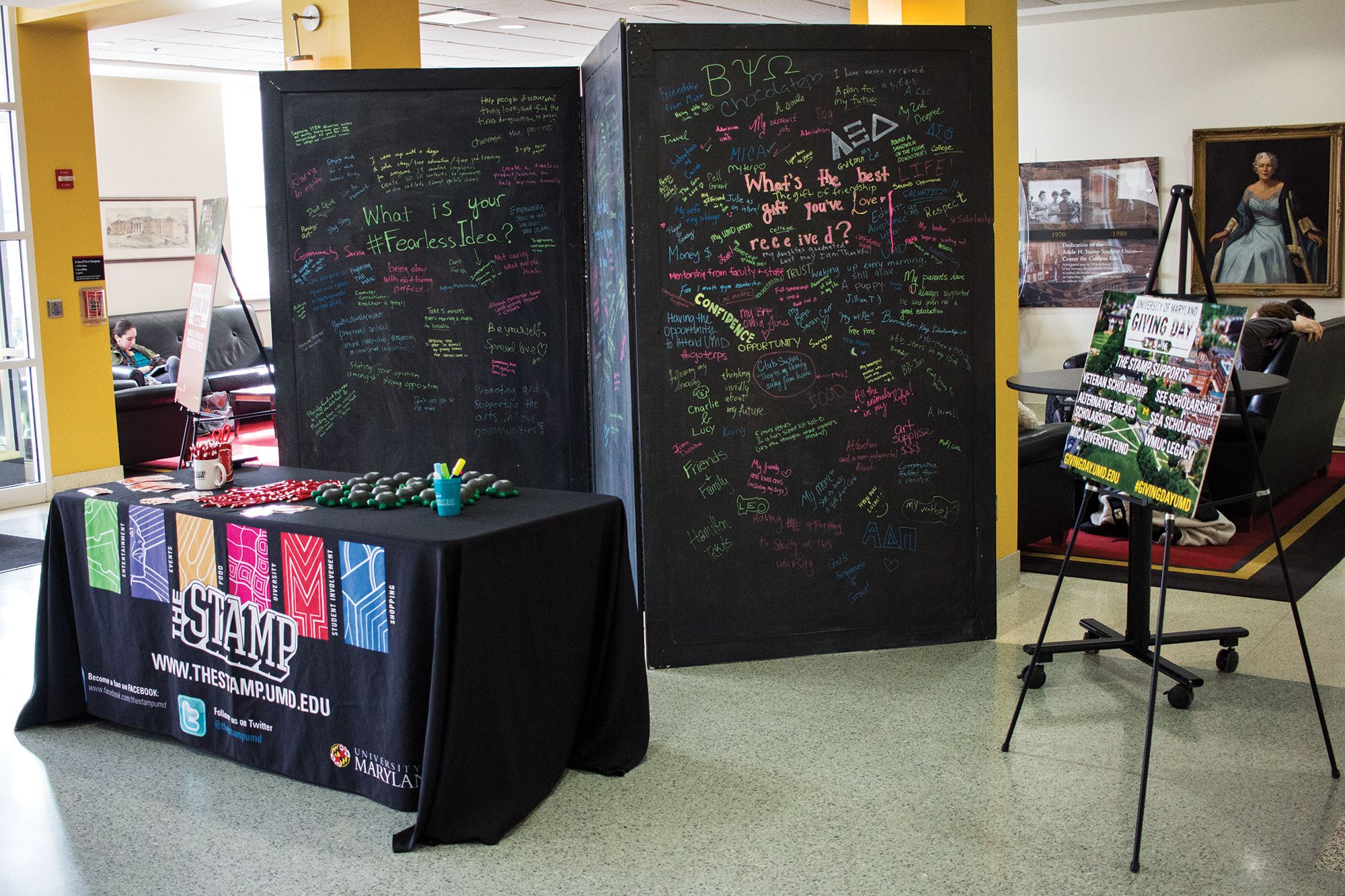

My social media feed was bombarded March 6 with posts promoting the University of Maryland’s Giving Day. On Giving Day, each academic college and campus office sets up a fund and promotes its own fundraising goal, encouraging students, faculty and their families to donate money to the offices and departments that impact them most. The wealthiest donors even pledge to match certain donation amounts with their own funds.

Frankly, the practice is insulting. Most students and their families already pay thousands of dollars every year in tuition and fees. Undergraduate student workers, graduate students, staff and some faculty are already grossly overworked and underpaid. Asking them to take even more out of their paycheck to support their own department is exploitative and wildly hypocritical.

More broadly, the aggressive focus on private giving comes at the same time that those departments are not adequately funded by the university’s existing reliable and consistent revenue sources. Critical services, scholarships, faculty salaries and programs increasingly depend on individual donations, private grants and large fundraising events.

The privatization of university resources hurts the university community. Private money is an unsustainable source that can be doled out at the whim of the donor without institutional accountability or oversight. A wealthy donor can offer to match funding one year and take it away the next. A donor can steer the use of their funding to match their own interests — students and faculty, on the other hand, have no voice on this university’s Finance Committee.

When private donors are the dominant voices, we get an Iribe Center that doesn’t have enough space for undergraduate students. We get a massive Cole Field House that displaces student parking and student groups in favor of a greedy athletics budget. We get a university so insistent on pursuing development in College Park that it leaves our most vulnerable residents and students behind.

When financial aid, facilities improvements, research grants and more are neglected in favor of the desires of the wealthy, we abandon our educational mission and become a facilitator of private greed and exploitation. And when critical services don’t get the consistent revenue they need and program workloads are devoted to fundraising, there is less time for staff and faculty to care for students or help them learn.

The result of all this is that students from wealthy families get ahead, compounding their existing privileges, while students without access to those networks are left further behind. Worse, it may be more challenging for them to be admitted to a university under a system that increasingly rewards those who can pay full tuition and whose parents can donate or claim a legacy connection. It doesn’t just happen at private schools; public schools like this university are guilty, too.

Students and employees at this university shouldn’t have to be unpaid public relations officials, development coordinators or recruiters. And we cannot be complacent and allow wealthy donors to believe this university exists to serve them, uphold their interests and churn out people who look, think and act just like them.

Our administration’s choice to prioritize fundraising in an endless pursuit of higher rankings and prestige has helped create the outsized influence of wealthy donors at the expense of students and workers. To combat the malicious infiltration of private money into our public university systems, we must radically shift our university’s priorities as well as our tactics for eliciting support.

The conversation around future university leadership must also discuss changes in how finances are governed, making all information transparent and publicly accessible and opening positions to students and employees to provide input on the budget. There are a wide variety of actions we can take, but no matter what, this university should work for its students and employees, not its donors.

Olivia Delaplaine is a senior government and politics major. She can be reached at odelaplaine15@gmail.com.