It seems like every other day a new rap beef surfaces, starts trending on Twitter and the world watches with a childlike fascination as artists exchange blows through a series of tweets or diss tracks. If somebody instigates an argument with a rapper, it is expected that the rapper will fight back 10 times harder because the rapper has to emerge as the one on top.

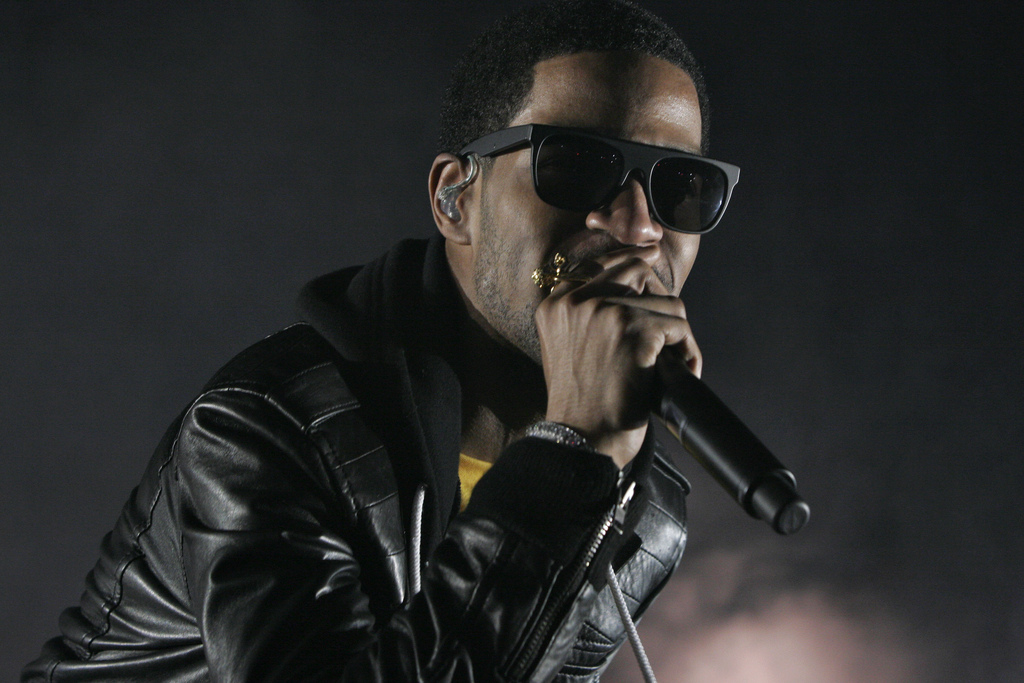

But Drake’s “Two Birds, One Stone” diss track — Drizzy’s shot at Kid Cudi, who checked himself into rehab for depression and suicidal urges in early October — was met with backlash on social media, even though rappers are expected to clap back at public disses.

So what made Drake’s shot so low?

Depression is an illness that pervades the lives of everyday people, pop stars being no exception. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, 6.7 percent of adults in the U.S. experienced a major depressive episode in 2015. A disease with no obvious physical effects, Cudi’s depression went unnoticed by his fans until he boldly wrote an open letter about his personal struggles in which he used the word “ashamed” several times to describe his feelings. Cudi felt the urge to be apologetic when describing his depression, and while this may be odd coming from anyone else, his position as a black rapper easily made his heartbreaking and honest letter a stark sign of weakness.

Rappers, navigating an art with major focuses on machismo and hedonism, are rarely open about their personal struggles outside of their music. Through delicately crafted lyrics, rappers control how big of a window the world has in seeing their most vulnerable states — and retaining control over this vulnerability is crucial, as allowing yourself to be so emotionally exposed contradicts the tough, masculine archetype of today’s rap star.

Whether listeners realize it or not, rappers are very open about mental illness in music, but are hardly ever candid enough to reveal their struggles in an open letter to fans. We see several examples of rappers describing the symptoms of the illness, but rarely offering a solution that could extend to their audiences. Even in the early days of gangsta rap, depressive symptoms had their fair share of mentions from rappers such as DMX, Tupac and Biggie Smalls.

In his 1994 song, “Suicidal Thoughts,” Smalls describes to Puff Daddy his laundry list of reasons why he should end his life, at one point rapping “I want to leave, I swear to God I feel like death is fuckin’ callin’ me/ Naw, you wouldn’t understand” as Puff Daddy’s stifled plea for communication is heard in the background. Throughout the song, Smalls describes feelings of low self-worth and emotional numbness that those afflicted by depression could easily relate to. But his lyrics fail to convey the helplessness that comes with the illness as well, as Smalls approaches his feelings how a gangster is expected to: without emotion. We get the diagnosis, but never the cure.

Since then, there seems to be an increased dialogue surrounding depression in rap, though this has done little to destigmatize the illness. Kendrick Lamar’s explosive 2015 album To Pimp A Butterfly deals with themes such as suicide and depression. He ends the melancholic track “u” by describing how money can’t cure depression, as he raps “The world’ll know money can’t stop a suicidal weakness.” Even rappers, surrounded by the perks of making it big, can feel depressed.

Drake, despite contributing to the stigma of mental illness with his diss, has described the feeling of isolation felt by depressives — namely, isolation that money and fame can’t treat. On his 2009 track “Fear,” he illustrates the often futile pursuit of solace through drug and alcohol use, as he raps “You know I spend money because spending time is hopeless/ And know I pop bottles because I bottle my emotions.” This sentiment is echoed in countless Future tracks, as the rapper portrays much of his drug use as self-medicated treatment for his personal demons.

But Cudi didn’t reveal his depression by spitting tragically clever lyrics or verses that described rampant drug use to deal with his pain. Instead, in a refreshingly humane letter, Cudi described his feelings of being overwhelmed and his need for actual treatment. He bridged the gap that rap creates in promoting positive changes to combat depression. That makes Drake’s diss aimed at Cudi’s humanity even more deplorable as his efforts to destigmatize depression was reduced to a sign of fragility.

A hero to his fans, Cudi felt the need to preemptively apologize for his letter. And while this may initially be met with confusion, considering the brutal nature of the rap game and the push for manliness, it is understandable. Cudi apologized for not living up to rap’s expectation of a strong, tough character — but perhaps his failure in meeting this expectation is precisely what rap needs to help its listeners struggling with mental illness.