Although wheat products are easy to find in any aisle at a grocery store, scientists have long thought the genetic code of this staple grain was impossible to decode.

But a recent discovery by University of Maryland researchers could help solve that problem — and become pivotal in combating issues related to population growth and climate change.

This university was one of seven in the U.S. involved in the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium, a group of 73 research institutions across the globe. The consortium published a completed and heavily annotated description of the wheat genome on Aug. 17.

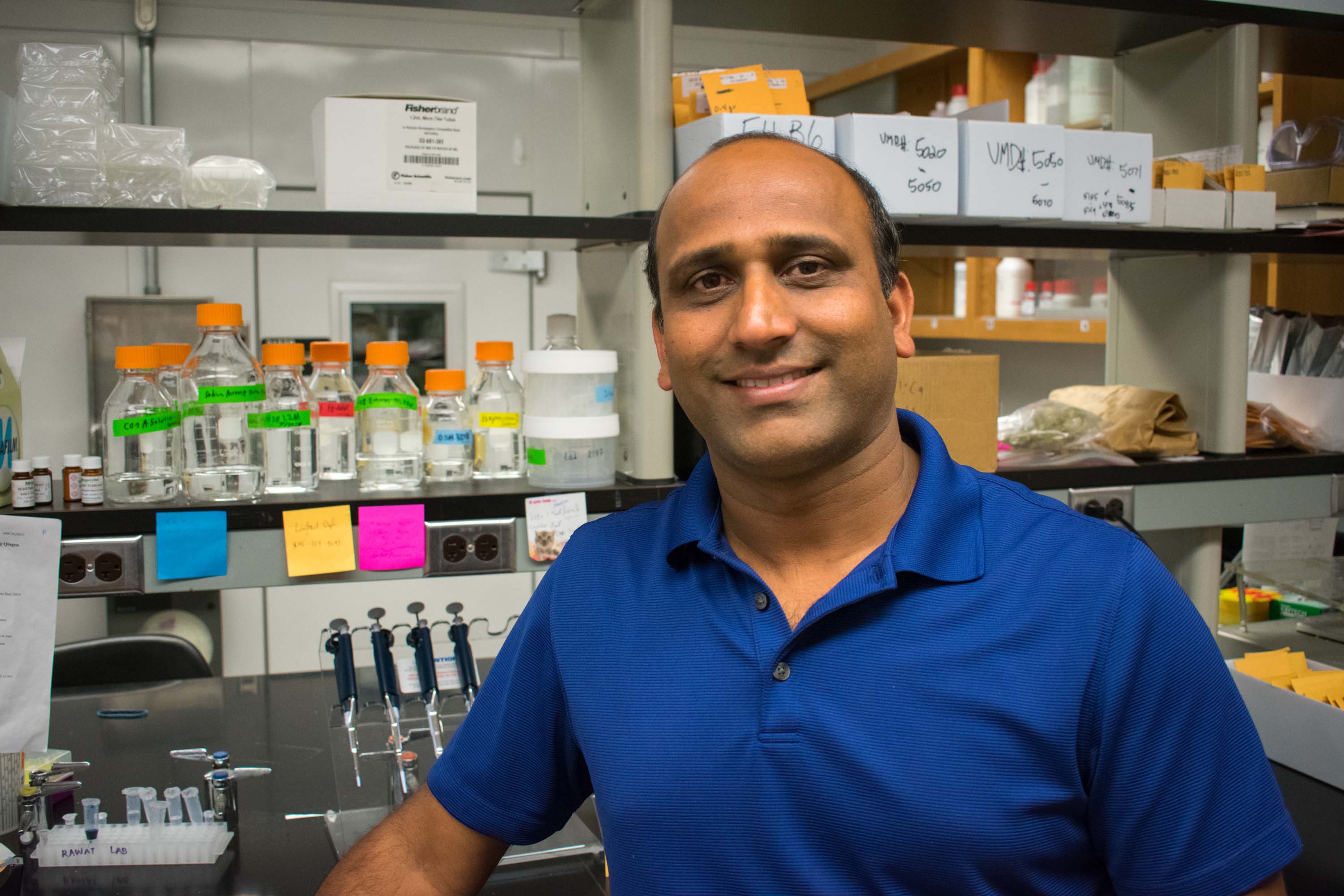

“We were able to achieve what was thought of as impossible,” said Vijay Tiwari, the leader of the Small Grain Breeding and Genetics program at this university. “It’s an exciting era for wheat scientists.”

[Read more: A revamped electric car charger is UMD’s Invention of the Year]

Tiwari got involved with the project in 2014 and used a technique called radiation hybrid mapping, which serves as a framework for assembling the genome after it is taken apart, to help decode the genome. The mapping helps scientists manipulate the sequence while they study it.

Wheat is the world’s most widely cultivated crop, but its genome is incredibly large and complex and was once thought of as impossible to understand, said Samantha Watters, assistant director of this university’s agriculture and natural resources college.

The consortium’s 13-year-long research project could be influential in the world of agriculture, Watters said. Kellye Eversole, executive director of the IWGSC, added that the project could assist in improving wheat quality, increasing production yields despite the negative effects of climate change, and furthering the potential for sustainably grown grains.

James Yorke, a math and physics professor at this university, helped developed a software called MaSuRCA in 2013 with this university’s Genome Assembly Group. The software helps researchers deconstruct DNA and understand it in small pieces like a “jigsaw puzzle.”

[Read more: UMD researchers received $2 million from the Energy Department to develop solar technology]

“Once you have one reference genome,” Yorke said, “All the wheat in the world can be compared to it.”

For instance, a wheat disease called rust is a common problem for growers, Yorke said. The genome can help prevent outbreaks.

“If you know what the DNA sequence is, you can try to figure out which variance of wheat has resistance,” he said.

This university’s Genome Assembly Group first discovered a version of the wheat genome in late 2017, but the consortium’s version is more complete and heavily annotated. The consortium will continue to annotate and improve the quality of the sequence, Eversole said.

As the world’s population continues to grow rapidly, the improvement of wheat production is essential and needs to increase by between 50 and 60 percent, Watters said.

“In order to meet that need, knowing the genome in wheat is huge,” Watters said. “It allows us to really understand what genetic components you actually see in the crop and how that factors into the sustainability and longevity of the crop.”