Artists’ Books and Africa

To get to the new exhibition “Artists’ Books and Africa,” Smithsonian librarian Janet Stanley says with a grin, “You have to go through ‘Hell.’”

Stanley is casually referring to the “Hell” section of “The Divine Comedy,” a fantastic exhibition also currently on view at the National Museum of African Art. The entrance to “Artists’ Books,” which Stanley curated, is just inside the “Hell” section.

With thought, though, her words carry a little more weight and echo in the mind as Stanley describes the intricacies of each of the 25 artists’ books on view. To create the amazingly innovative and beautiful works, the artists in some cases had to endure or portray unbridled pain and hardship, either personally or ethnically. In a way, to create the stunning works in this exhibition, they had to go through hell.

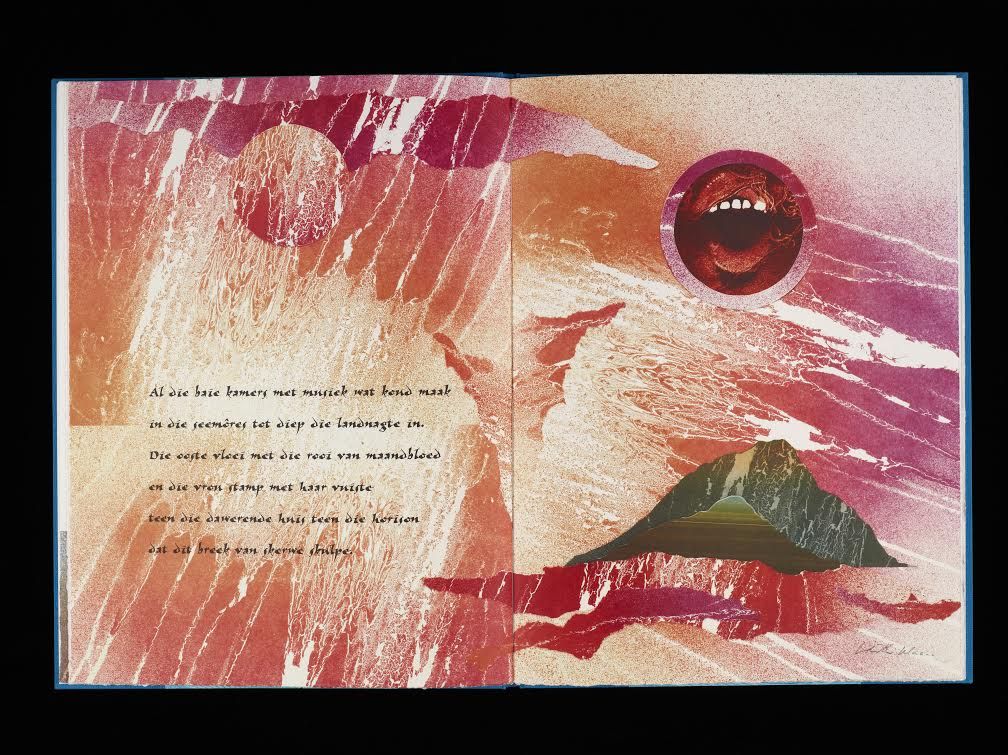

Butterfly Hill, Butterfly Woman is an Afrikaans poem written by Wilma Stockenström and illustrated by Judith Mason. The illustration seen by visitors is intensely red, slashing and piercing with fierce strokes of color. In one area, a crimson mouth with stark white teeth seems to scream out. “That gaping mouth —” the exhibition wall text asks, “could it signify pain from childbirth or intercourse?”

“The woman bangs her fists against the booming house,” Stockenström writes in Afrikaans, as translated in the wall text. “The East flows red with menstrual blood.”

“Some of these books are by African artists, but they’re not all by African artists,” Stanley clarified. “They’re artists for whom Africa is the subject of their artist’s book.”

This leads to an interesting mix of imported tradition and indigenous — of the outside view and the view from within. The interplay among artists at a global scale lends new perspectives on some of recent history’s most trying issues.

“Most of the African artists who have done artists’ books are people who have lived or worked or studied overseas, where they have been exposed or introduced to this genre,” Stanley said.

The entire idea of creating an artist’s book seems to be imported, a difficult concept when paired with subject matter pointing to the horrors of European colonization.

Stanley shows another piece, Sound for the Thinking Strings by white South African artist Pippa Skotnes. The title is based on a poem from the San culture.

“The San people, who are sometimes known as the bushmen in southern Africa … are indigenous people who have been there for millennia,” Stanley said.

Perhaps 60 millennia, according to genetic evidence cited on the exhibition website.

“And their civilization has basically been destroyed by European influence over the last several centuries,” Stanley said.

Is it at all darkly ironic that Skotnes, a person of European descent, is chronicling a people destroyed using such an imported artistic technique?

“I don’t think so,” Stanley said. “I think she sees this as sort of a salvage project.” In the book, Skotnes illustrates some of the culture’s last surviving oral histories, themselves recorded decades earlier.

To get to a place where this story is possible and even necessary, people went through hell.

Other works deal with extremely contemporary issues, like The Ultimate Safari, written by the late Nobel Prize winner Nadine Gordimer.

“The story, though it’s fiction, is based on a reality,” Stanley said. “And the reality has to do with refugees, which is a very topical subject. These are refugees from Mozambique who walked on foot across Kruger National Park to get to safety in South Africa.

“But it’s a very perilous journey, like the migrants coming into Europe today. It can be very treacherous,” Stanley said. “And the women who were invited to illustrate this book are not artists — they are women who had actually made that trek themselves, they were refugees. … And when the story was first read to them, they couldn’t believe that this white, South African woman could’ve known their story so well.”

“We think a safari is a tourism thing, a fun thing,” Stanley said. “And this is the ultimate safari. You’re trekking across this land, you may die in the process. … It’s very ironic in terms of the ‘ultimate’ safari. It resonates today with this story about what the Pope was saying yesterday: Think of these refugees as human beings.”

To get to tell their stories, these women went through hell. And now through Sept. 11, 2016, they’re on view at the Smithsonian.

The National Museum of African Art is nearest to the Metro’s Smithsonian Station.