This university and Washington’s Phillips Collection stand on the precipice of a grand new partnership.

How fitting, then, that the first Phillips exhibition to open since the announcement chronicles partnerships as well.

From the friendship of two collectors set on preserving great artworks of their time to partnership between artists supported and treated by a country doctor in the fields outside Paris. From the family tie of mother-and-son artists to the bond of two exiled painters working together in the foothills of the German Alps.

From the passionate romance of an artist and his dying lover to the civic pride that connected a Swiss city to a beloved Spanish painter. Even in the dichotomous relationship between two Tahitian young women, it’s all about partnerships.

The exhibition presents — for the first time in the United States — highlights from the “sister collections” of Rudolf Staechelin and Karl Im Obersteg, two Swiss friends who collected during the early decades of the 20th century. The collections normally reside in the Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland.

“This exhibition is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” said co-curator Renée Maurer. Artists on view include Pablo Picasso, Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro, Marc Chagall, Édouard Manet and Wassily Kandinsky, among others.

The exhibition, which opened Oct. 10, portrays many partnerships like Staechelin and Im Obersteg’s, using tactful organization to create an immersive and at times utterly fascinating conversation among works and artists.

Van Gogh

In Auvers

One of the early champions of impressionism, Pissarro, is presented near the front. At least in this show, he is the cog around which impressionism turns.

In one work, he shows a rural pathway traversed by two wayward peasants. The road leads to Auvers-sur-Oise, Maurer said, a small town in the countryside outlying Paris.

The town is the surprising nexus of much of impressionism as well as the exhibition’s first and most impressive gallery.

“During this time, Pissarro invited Cézanne to paint outdoors with him,” Maurer said. “Pissarro said, ‘Paint outdoors, it might change the way you make art.’ And it did.”

Cézanne’s color palette became brighter as he explored rural subject matter in the town of Auvers itself. One site he portrayed was the home of Dr. Paul Gachet, a well-known physician and arts benefactor.

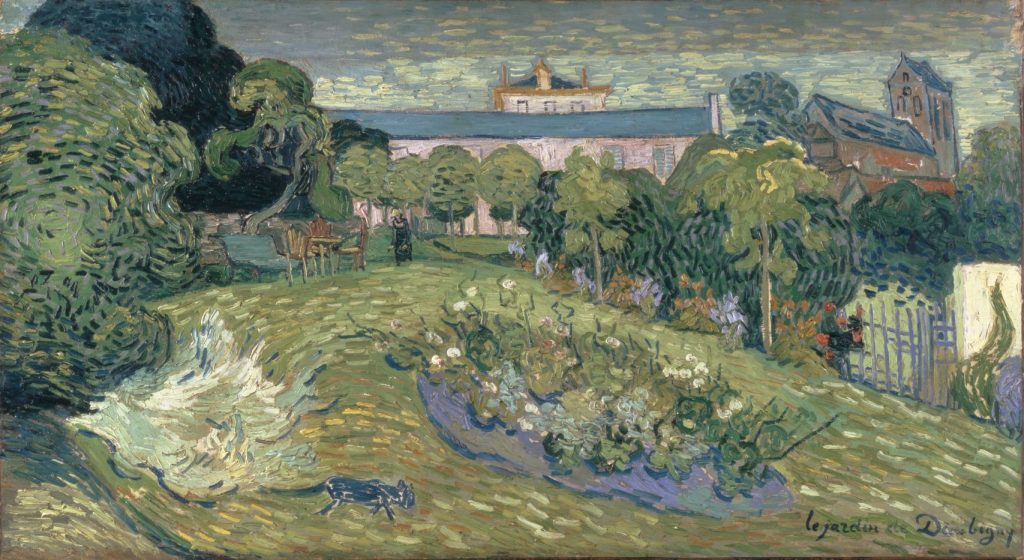

Gachet’s two callings intertwined when he treated van Gogh, who had sought him on Pissarro’s recommendation. While in Auvers under Gachet’s care, van Gogh painted the house and garden of the late French painter Charles-François Daubigny, who the Dutch artist admired. The painting is a florid tapestry of undulating emerald.

Pissarro’s influence on these artists and art itself is impossible to overestimate, as this show makes abundantly clear. The too-often neglected painter (fascinatingly born in what is now the U.S. Virgin Islands) had much to teach and many eager students, including Gauguin.

“Pissarro would mentor Gauguin when Gauguin was learning about impressionism,” Maurer said. “He and Pissarro and Cézanne would paint together outdoors.” The artists’ relationships presented are extraordinarily fascinating.

However, Gauguin had no success in Paris. He traveled to Tahiti in search of an exotic creativity, but instead found a colony watered down by European influence. He explored this theme in “When Will You Marry?” — a main highlight and major wrinkle on this fantastic exhibition.

The work contrasts two Tahitian women. One is dressed in exotic, provocative garb. She has a flower in her hair and her blouse dips enticingly around her chest. The other is shown in colonial European attire, with stern face and a gesture historians believe might be a warning.

This is likely the last time this work will be on public view, at least for a great while. It was recently sold to a mysterious buyer (thought to be the state museums of Qatar, which have quietly bought up many great artworks in recent years) for a reported $300 million, which would make it among the most expensive artworks ever sold.

Picasso

In Basel

The politics of the Staechelin collection are a cacophony of squabbling, dealing and gobs and gobs of money. It’s only abhorrent that such great artworks and the citizens of Basel who love them have to get caught in the middle.

And unfortunately for them, this scenario is nothing new. Extended wall text from the exhibition recounts a time when the cash-strapped Staechelin heirs tried to pull the same stunt in 1967 — but with a very different outcome.

The collection attempted to sell two Picassos, “elicit[ing] especially vehement responses from the museum, the city, the state … and local residents,” according to the text. Under pressure, Staechelin’s son agreed to sell the works to Basel for “much less than their market value” — nearly a quarter of which was raised by local residents’ fundraising.

Picasso himself was so moved by this show of support that he eventually donated four more of his works to the museum. It showed what partnership can do for great art.

Unfortunately, Paul Gauguin is 112 years dead, and $300 million is a tad more than the canton of Basel can be expected to pay.

(The Picasso works on view, for their matter, show an artist testing himself in four different portraits that chronicle periods in his life and work. They are remarkable in their own sense, but not among his greatest works.)

Chagall

In Exile

A visitor looking at Chagall’s three contrasting portraits of Jews remarked to his family that they were interesting because “normally you just see goats flying around,” referencing a banal but common Chagall theme.

It’s a shudder-worthy comment, but it’s also evidence of how remarkable Chagall’s pieces on view truly are.

Born Moishe Segal and raised in an observant Jewish-Russian family, Chagall returned to his family home from France in 1914 and was kept there by World War I. This gives the three portraits of Jews a troubling air of familiarity yet foreignness.

He dresses a transient wanderer in accurately represented prayer regalia, writes out the Kaddish prayer in one work’s background and even lists his favorite artists in English, Hebrew, Greek and Cyrillic in another. The works reveal competing backgrounds simultaneously in exile and back at home.

The great undercurrent of this time period is exile, due to war or unrest or something else. One can see hints of it in the exhibition, rearing an ugly head here or there, but not as great a specter as one might expect.

It is clearest, interestingly, for the Russians.

(Kandinsky and countryman Alexej von Jawlensky painted together in the German market town of Murnau while the two were “abroad.”)

Monet

In Death

Jawlensky had also met and worked with Henri Matisse and Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler.

Im Obersteg met Hodler through fellow Swiss artist Cuno Amiet, from whom he had purchased his very first artwork, yet another relationship.

Hodler explored partnership in a very literal way, shown in four of his works on view that capture the profound effect of Hodler’s mistress on his work.

“They represent a relationship between artist and subject that was very intense,” Maurer said. “They had a very passionate relationship: she was 20 years younger, she was an actress, she bore his child in 1913.”

“And that same year, she had cancer. So these three really show her dealing with illness,” Maurer said. “You see her upright, strong after surgery; and then at an angle, ill; and then at death.”

“When Will You Marry” by Paul Gauguin contrasts two Tahitian women, one exotic and sexual, the other stern and wearing European clothing. (Image courtesy of the Phillips Collection/The Rudolf Staechelin Collection/(c) Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler)

Pablo Picasso’s “Harlequin With A Black Mask” shows a ballet dancer in costume, an example of the Return to Order art movement. (Image courtesy of the Phillips Collection/The Rudolf Staechelin Collection/(c) 2015 estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Marc Chagall’s “Jew In Black and White” portrays a vagrant dressed in the artist’s fathers Tallit (prayer shawl) and tefillin (wrappings). (Image courtesy of the Phillips Collection/Im Obersteg Colleciton on permanent loan to the Kunstmuseum Basel/(c) 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris)

“The Garden of Daubigny” by Vincent Van Gogh shows the yard of one of Van Gogh’s favorite artists, painted while he was receiving treatment in Auvers. (Image courtesy of the Phillips Collection/The Rudolf Staechelin Collection/(c) Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler)

Following his first wife’s death, Claude Monet turned to stoic, solitary landscapes, like “Calm Weather, Fécamp,” the only Monet on view. (Image courtesy of the Phillips Collection/The Rufolf Staechelin Collection/(c) Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler)