WALLACE LOH KNOWS he has been on stage for the past three years.

Whether he is buying a quart of milk or slogging through meetings during one of his 15-hour workdays, someone will recognize the university president. He’s often stopped everywhere he goes, whether it’s at a stationary bike at Eppley Recreation Center or at 11 p.m. at an off-campus grocery store.

Since he became president on Nov. 1, 2010, this has been Loh’s life. His path here has been riddled with struggles and constant change. It’s included a childhood in near-poverty. It’s included immigrating twice. And it’s included rejection, whether from law school, jobs or colleagues.

But each roadblock has helped shape Loh’s presidency. The university unexpectedly leaped into the Big Ten, began exploring a partnership with Washington’s Corcoran Museum of Art, partnered with the University of Maryland, Baltimore and started redeveloping College Park.

Critics still say he’s just a man from the outside. He’s just an impulsive person, they say, unafraid to abandon tradition at the state’s flagship university.

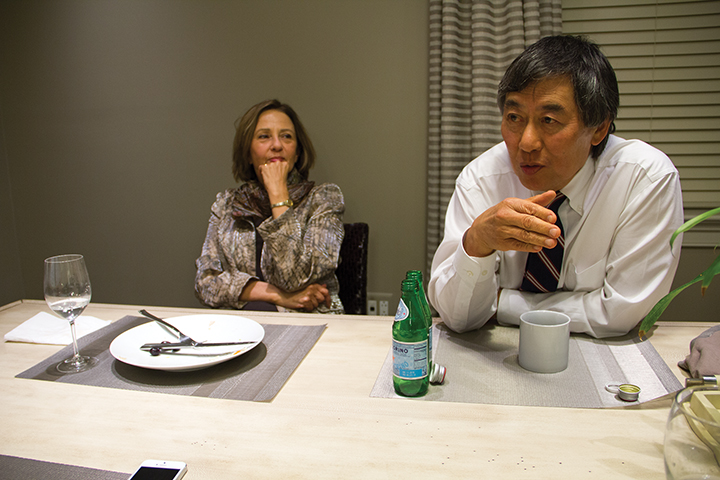

“That’s true,” Loh said while eating dinner with his wife, Barbara, earlier this month. “That’s precisely why they hired me.”

President Loh

FROM RICHES TO RAGS

He should have been the Donald Trump of Shanghai.

That’s what Loh likes to say, anyway. He should own a lavish mansion in Shanghai. He should oversee an expansive service staff and a generous inheritance.

In 1945, Loh was born into China’s privileged elite. His grandparents owned five blocks of downtown Shanghai. As their only grandson, Loh was in line to inherit the expensive properties.

But crisis struck when Loh was 4 years old. Mao Zedong, an oppressive communist dictator who instituted policies that triggered nationwide famines, unseated the nationalist government. As an employee of the former government’s Chinese foreign service, Loh’s father seemed destined for execution.

So the Lohs sought political asylum in Lima, Peru. They replaced a life of luxury with a host of uncertainties: no jobs, no money, no inkling of the hardships that awaited them.

Like most Chinese immigrants in Peru, Loh said, his parents began operating a small mom-and-pop grocery store. They had never owned a business, but they scraped together enough money for life’s necessities.

In the back of the store, they erected a few walls and a roof to create a living room, dining room and “bathroom of sorts,” Loh said, complete with a large dirt patio outside. Kerosene lamps acted as their makeshift heaters.

Each day after classes, Loh stocked shelves, weighed food and worked as a cashier until closing at 10 p.m. He dreaded the end of the school week on Friday afternoons.

Oh my God, he would think. I’m going to spend two whole days working at the grocery store.

And that was the routine every week until Loh graduated high school at 15 years old. (There was no sixth- or 12th-grade equivalent in Peru, he said.)

His parents wanted more for their only son, experiences beyond the day-to-day grind of running a grocery store. So Loh applied to dozens of schools in the United States before receiving acceptance to Iowa Wesleyan College. His parents gave him $300 — their entire life savings — and let him start a new chapter.

Loh knew “nothing” about the United States. He didn’t speak a word of English.

‘WHERE’S THE MAID?’

Loh landed in Miami International Airport, where he saw people filing on and off a moving staircase. What was this? Loh thought. He had never seen an escalator.

He eventually proceeded to the Greyhound bus station and caught a ride to Iowa Wesleyan’s campus in the corn-producing town of Mount Pleasant.

There, he faced a litany of new challenges. Forget the indiscernible lectures, the confusing customs, the pile of seemingly impossible homework assignments. He didn’t know what to do with his laundry.

In Peru, everyone, no matter how poor, had a maid, Loh said. Maids were inexpensive, and they were the ones who took care of laundry and many household chores. So, naturally, Loh asked his roommate, a senior, when the maid was coming to do the laundry.

“Oh, the maid,” his roommate said. “You have to see the head maid of the college. But in this country, we don’t call it the maid. We call the person the dean of students.”

Loh, who had never seen or heard of a washing machine, took his laundry to the office of the dean of students, whom he described as an elderly, strict woman who never cracked a smile. Loh propped the bag of dirty clothes on her desk.

She looked at him sternly before she saw a group of male students giggling outside the window, Loh said. It was his roommate with a group of friends.

The dean took Loh’s laundry and told the freshman to return in a couple of days, when his clothes would be freshly washed.

Fortunately, it didn’t take him long to understand American culture. Talk to Loh today about his goals for this university or watch him give a speech, and it will inevitably lead to talk of innovation and entrepreneurship. These must be the cornerstones of any major public research university, he says. That’s why, in 2012, this university partnered with Coursera, a technology company that hosts free online classes from 33 universities worldwide.

After nearly failing his freshman classes, he said, the naive 16-year-old transferred to Iowa’s Grinnell College to complete his psychology degree. He was later accepted into Cornell University’s psychology graduate program.

President Loh

THE DREAM

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, some 250,000 people were preparing to gather in the nation’s capital for the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963.

At 17 years old, Loh didn’t know much about Martin Luther King, Jr., but he wanted to experience the much-talked-about demonstration. He hitchhiked more than 400 miles from Harvard, where he was attending summer school, to Washington.

Loh doesn’t shy away from showing emotion; he tears up when he talks about many things, including King’s “I have a dream” speech. It was the speech that inspired Loh to earn a law degree and fight for social change.

But every law school he applied to in 1965 rejected him. So he enrolled in the University of Michigan’s doctoral program before reapplying to several law schools six years later.

By 1971, the civil rights movement had transformed the country. With affirmative action in place, Loh received admission and generous scholarships from Harvard and Yale.

“I’m the proud product of affirmative action,” he said. “That doesn’t embarrass me.”

He chose Harvard and called Yale admissions officers to inform them of his decision. Before they let him finalize his choice, though, they asked him to speak with one of their student interns. Her name was Hillary Rodham.

She spoke of how the corporate, button-down types attend Harvard, and those who want to institute social change go to Yale. After a two-and-a-half hour phone conversation, Loh called the Yale admissions office to secure a spot in the incoming class.

He met up with Rodham and her then-boyfriend, Bill Clinton, whom fellow students fondly called “Bubba.”

The next time he saw “Bubba,” Loh was standing in a long line of people at a White House event in the 1990s, waiting to shake the then-president’s hand. Loh made his way to the front of the line.

“I don’t know if you remember me, but Hillary helped me go to Yale Law School,” Loh said to Clinton.

“Well of course I remember you!” Clinton responded.

It didn’t matter whether Loh’s former classmate really did remember him. All that mattered was that, in those few seconds, Loh felt as if he was the only one in the room who mattered. This, he said, is why Clinton is a great politician.

So Loh uses his former classmate’s tactic. He will stop and talk with almost anyone who approaches him, even if he is 10 minutes late to his next meeting.

Whether Loh is in a meeting, working out at ERC, cheering at a sports game or buying a quart of milk in a grocery store, he is a local celebrity of sorts. He cannot let anyone feel ignored.

“I could say that he is my president and I work for him,” Athletic Director Kevin Anderson said. “But it goes beyond that. He’s somebody who’s a mentor, who’s a teacher, who’s a colleague and also who is a friend.”

GUT INSTINCT

As a professor at the University of Washington School of Law in the 1980s, Loh was “blissfully unaware” of what went on outside his classroom. He enjoyed regular ski trips during school breaks, when he would grade papers on ski lifts.

He was a quirky professor who never used prepared notes during class. He did not utter a declarative sentence throughout his 50-minute lecture — he peppered students with questions, quickly pointing from one student to the next. He was the maestro. His class was the orchestra.

When Loh called on a student, he or she had to stand up. The message was clear: A lawyer’s day is a series of questions.

During one class, Loh grilled a student for 40 minutes. The young man fainted, and Loh called 911. An ambulance arrived to take the student to the hospital after suffering an apparent anxiety attack.

Martin O’Malley pull quote

His tactics may have terrified his students, but they impressed the law school’s faculty and administrators. A few years into teaching, Loh was appointed dean of the law school, making him the first Asian-American law school dean in U.S. history. He traded in his typical laid-back attire — Oxford shirts, corduroys and sneakers — for a suit.

He served as law school dean for five years until 1995 before bouncing around a series of posts: provost at the University of Colorado, Boulder; policy director for then-Washington Gov. Gary Locke, the country’s first Chinese-American governor; dean of the arts and humanities college at Seattle University; and provost at the University of Iowa.

“In real life, [Loh] is your kind of introverted professor. He’s a true introvert, not political,” Barbara said. “And then he turned out to be this political animal.”

Being president of a flagship institution is the most political nonpolitical job in the state, Loh said. That doesn’t mean he has abandoned his quirky approach, though.

As president, Loh still does not use prepared notes when delivering speeches. He engages his audience, once leading a room full of people gathered to celebrate the computer science department’s 40th anniversary in a chorus of “Happy Birthday.”

“He doesn’t have an ivory tower, ‘pull up the drawbridge of the castle’ sort of style,” Gov. Martin O’Malley said. “His leadership is suited for these times.”

Loh credits his years as law school dean and a member of Locke’s cabinet as the experiences that helped prepare him most for his current post.

As policy chief, Loh had to distill every issue into three or four bullet points for Locke. “I had maybe three minutes per issue,” Loh said.

That’s what it’s like as university president.

“There is never enough information. Like the Big Ten. Do I really know if it’s going to work out? No, I don’t know. The important thing is to make a decision based upon incomplete information,” Loh said. “And a lot of times it comes from your gut. But it’s a gut that’s informed by experience.”

President Loh

FACING CRITICS

There are still plenty of critics, though. Loh realizes he will never have enough time to please everyone.

One year into his presidency, Loh faced a seemingly unsolvable problem: The athletic department was in dire financial trouble. It had depleted its savings and faced a deficit projected to reach $4.7 million in 2011 that would balloon to $17 million by 2017.

Loh ultimately cut seven teams from the university’s 27-sport athletic program: men’s and women’s swimming and diving, men’s tennis, acrobatics and tumbling, women’s water polo and men’s cross country and indoor track. He still cries when he remembers delivering the crushing news to the student-athletes — his daughter, who is in her 20s and works in the area, played soccer in college. Both he and Anderson said it was the most heart-wrenching decision they ever made.

State delegates, alumni and others wrote to Loh criticizing the decision. Michael Phelps took to Twitter to advocate for the swim team.

“The heavy handed, unrealistic proposal, as it currently exists, is an embarrassment to all of us who serve the citizens of this state in our legislature,” Del. Benjamin Kramer (D-Montgomery) wrote in a 2012 letter signed by 50 of his colleagues. “Each of the teams should be provided the opportunity to work with you and the athletic department to ascertain an equitable, prudent, and reasonable program.”

And in November, many felt Loh barreled into the Big Ten. He said the move would secure the financial future of the athletic department. But Loh and the Board of Regents finalized the deal in secret, prompting questions about the legality of the move.

“This is what happens when outsiders are hired to run things,” Washington Examiner sports columnist Rick Snider wrote in November 2012, after Loh announced the move. “They don’t care what locals want. … After all, Loh’s all about the money.”

Loh does not grow too attached to any idea or tradition, he said. He’s read the blogs but maintains he would not have done anything differently. And he has faced adversity far more daunting than a few negative headlines. Loh, after all, learned how to handle hagglers in a Peruvian grocery store by age 10.

Mike Miller pullquote

“He’s fearless when it comes time to making a decision,” state Senate President Mike Miller said. “He’s willing to move forward, even on perilous ground.”

LEARNING THROUGH STORIES

Over the course of one speech, Loh will quote or draw upon the experiences of Michael Jordan, Jesus, Yogi Berra, Socrates, Wayne Gretzky and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Just like when he was a law professor, Loh does not prepare notes before he speaks. He relies on experience and pulls from a file of quotes from great historical and athletic figures that fit his way of thinking.

“People will remember the quote,” Loh said. “It’s much less likely they’ll remember my statement or the moral lesson of that quote.”

At dinner on a Tuesday night this month at the president’s residence, Loh and his wife discussed how to be an effective and efficient leader. Loh used his favorite movie of last year, Lincoln, to explain how he negotiates.

The 13th Amendment, banning slavery, narrowly passed Congress. Lincoln got the swing votes by “basically bribing” Congress, Loh said. “This is how legislation gets made. I don’t bribe people. I need to have a dean support something if it’s really important — you know the dean wants something in return.”

“See, Wallace, I would say this is an amazing transformation from the sort of naive, clueless professor,” Barbara Loh said, smiling, “to this political, diplomatic administrator.”

To explain his rationale for joining the Big Ten and leaving the ACC after the university helped found it 60 years ago, Loh leaned on a quote from Berra, who is widely considered one of baseball’s greatest catchers: “The future ain’t what it used to be.”

Loh respects tradition but is determined to move forward. And he knows firsthand that nothing can be achieved alone. Others have offered critical support throughout his career.

So as he moves forward, he does not hesitate to look for partners: the Big Ten, the Corcoran, the University of Maryland, Baltimore, the rest of Prince George’s County.

“He understands the benefits that come from collaboration instead of looking at them as some sort of threat,” O’Malley said. “These are not times where it’s good to be a control freak or to be locked into the rigid, hierarchical approach of the past.”

And it’s OK to fail sometimes, Loh said. He has not always acclimated to new environments appropriately. But that’s how resilience and success are achieved.

Loh draws upon a Jordan quote to illustrate his point: “I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times, I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

President Loh

ANYONE CAN DO IT

On an October Saturday morning, hundreds of the university’s top prospective freshmen were seated in Stamp Student Union’s Grand Ballroom.

The university president was scheduled to give a speech at 9:15 a.m. Loh took the stage — no notes in hand — and spoke to the students and their parents for 21 minutes, integrating lessons and quotes from the people he regularly cites: Berra, Jordan, Jesus, Socrates.

He told the students and parents they were all Terps for the day. Then, he asked the entire audience to stand up. Take one step to your right, he told them. Now, one step to your left. Sit back down.

“I want you to be able to say when you heard the president of the University of Maryland speak,” Loh said, “that he moved you.”

After a few more jokes, Loh told the audience a story.

There was once a 15-year-old “LatinAsian” who immigrated to the U.S. He received a C minus-minus in college — “It was only out of pity it was not an ‘F’” — and thought his freshman year would be the death of him.

But one faculty member told the 15-year-old he believed in him more than the student believed in himself and promised him he would be able to receive his Ph.D. one day.

Well, Loh said, the student went on to graduate school, got a Ph.D., graduated from law school and had a career as an educator.

“That student,” Loh told the audience, “now stands before you as the president of the University of Maryland.”

Loh’s story is the American dream, he said. It’s a reminder of the evolution of our country. If that 15-year-old could eventually become the president of a major university, he told the audience, then they were all capable of anything.

President Loh

President Loh prepares to film the fall message to the students on the balcony of McKeldin Library