The updated University of Maryland Code of Student Conduct took effect Jan. 1, more than a year after the University Senate tasked a committee with reviewing and revising it.

The revised code, which was approved by the senate and signed by university President Wallace Loh, lowers the standards of evidence for student misconduct and changes the role of attorneys during hearings for potential breaches of student conduct, among other adjustments.

“Fundamentally, the student conduct process has not changed, however important updates were made,” Student Conduct Director Andrea Goodwin wrote in a campuswide email sent Tuesday afternoon.

[Read more: A UMD Senate committee votes to lower standard of evidence in Code of Student Conduct]

The standard of evidence in misconduct cases was lowered from “clear and convincing,” meaning it’s very likely but not certain that a code violation occurred, to “a preponderance of the evidence,” meaning it’s more likely than not that a code violation occurred. Under the new code, attorneys hired by students can no longer speak on their behalf during hearings and can only advise their clients.

The changes align with the standard of evidence for this university’s sexual misconduct policy, Goodwin wrote.

In addition to allowing students to advocate for themselves, the changes ensure power imbalances between students and lawyers will not be a problem, Andrea Dragan, Student Conduct Committee chair, said in December. All students also have a right to student defenders appointed by the Student Legal Aid Office, who are still allowed to speak during hearings, Dragan noted.

“You have a resource on campus in the Student Legal Aid Office that trains people with how to advocate on behalf of students and how to represent the students,” SGA President AJ Pruitt said. “I’ve been told by the Office of Student Conduct, and just by people around the process that stood on the boards, that oftentimes a student defender ends up being more informed in being able to create better arguments than an outside attorney.”

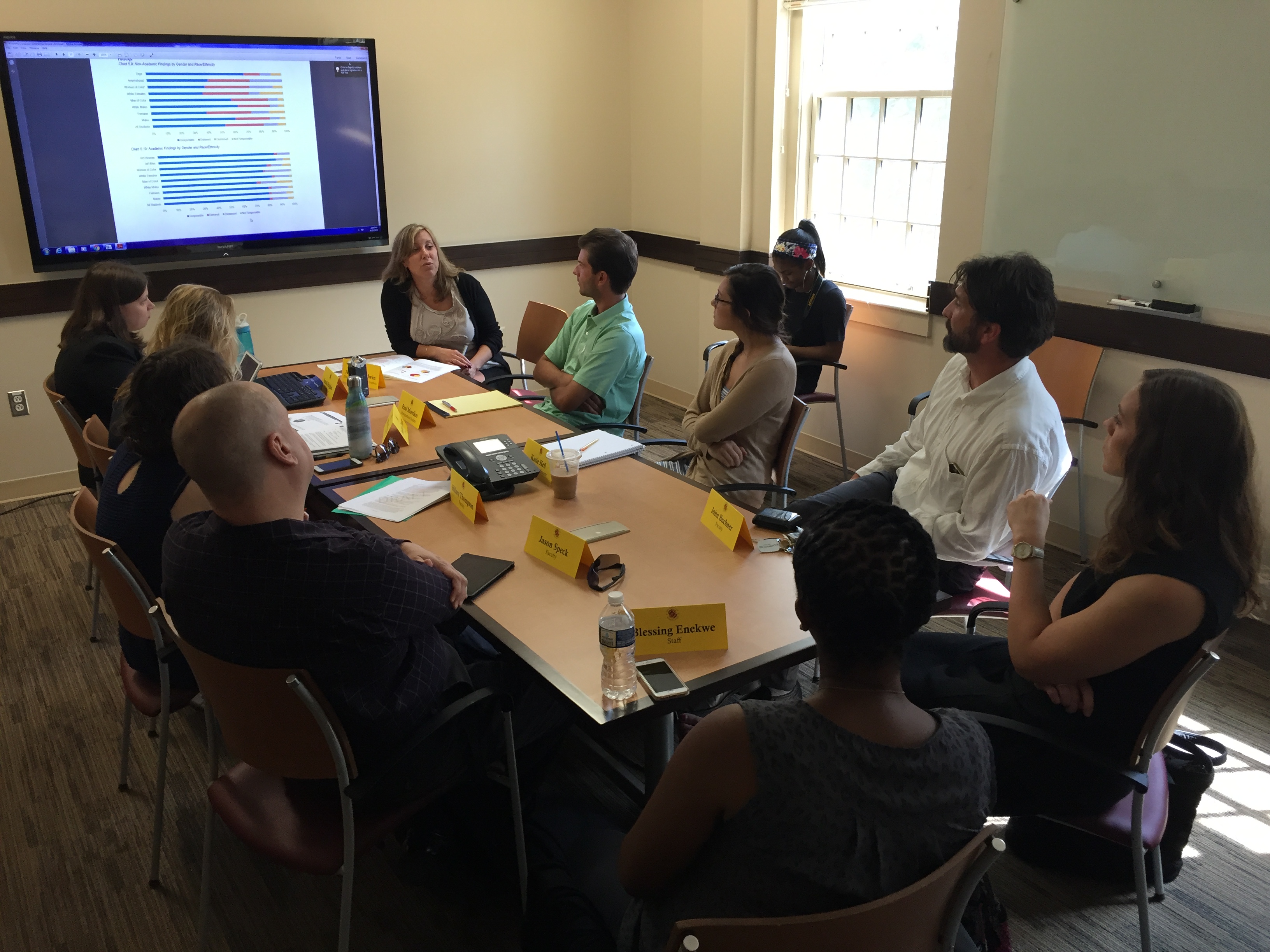

In September 2016, the senate tasked the Student Conduct Committee with reviewing the now-former policy and finding information from other institutions to expand definitions for prohibited conduct. The committee has since researched and held periodic meetings to discuss different aspects of the code and review elements that may need changing.

In December, the Student Conduct Committee approved suggested revisions to the code, including the lower standard of evidence and a recommendation to organize the code into three major components — student rights and responsibilities, prohibited conduct, and student conduct processes and procedures — and take out “unnecessary [and] outdated information.”

[Read more: With hate symbol ban not possible, UMD Senate considers alternatives]

After a string of hate bias incidents on the campus, the committee suggested removing “[i]ntentionally and substantially interfering with the freedom of expression of others” as a listed prohibited conduct. Goodwin said in November that this portion sends the “wrong message.”

“We don’t want students to feel like we’re suppressing them if they’re fighting back with somebody who is saying hate words,” she said.

The updated code revised this section to clarify that only lawful freedom of expression is protected, and directed students to the university’s guidelines for demonstrations and leafletting for further information.

“I think the revised section sends the correct message,” Assistant Director of Student Conduct Vanessa Taft said. “We wanted to make sure it was explicit that the university protects freedom of expression … [and] make students understand what is expected of them, and I think the revisions encompass that clearly.”

The new code reduces the use of “legalistic language” so students can better understand what constitutes prohibited behavior at this university, Tuesday’s email read. The revisions expanded the definitions of prohibited conduct to cover the types of misconduct commonly referred to the Office of Student Conduct.

Senior staff writer Leah Brennan contributed to this report.

CORRECTION: Due to a reporting error, a previous version of this story misspelled Andrea Dragan’s last name. This story has been updated.