Maryland softball infielder Skylynne Ellazar attended a recruiting camp as a high school sophomore, hosted by her team’s rival, Maui High School.

When she arrived, there were only Division II colleges, and she told the coach she wanted to play Division I softball.

“Well, Hawaii girls don’t go to D-I,” he responded. “It’s because we don’t get recruited to go.”

So, she left.

Ellazar had traveled to California in previous summers to play on elite-level travel teams because her native Hawaii didn’t offer the same exposure. Since middle school, she had her heart set on playing for a major school in a top conference.

“I’m not going to California every summer and spending all those hours and games to just be like, ‘Well, I just want to go to D-II,'” Ellazar thought as she left the prospect’s showcase.

That determination paid off when she earned a scholarship from Maryland. She’s started 89 games in the past two seasons as the first member of her family to attend a four-year university.

‘PARK RATS’

It was a typical summer day in Hawaii: Ellazar’s friends were at the beach, but she was at the park. Her brother, Tevan Devera, dragged her out of bed and they jogged, gear and all, to a field about two miles away.

After hitting in the cages, fielding groundballs and working out, Ellazar ran home. If there were weekend tournaments going on, the pair often stayed to watch.

“We were park rats,” she said.

That’s when Ellazar was in eighth grade and Devera was a senior. Under his supervision, she adopted a work ethic and love for baseball, and later, for softball.

She started playing tee ball around age four and was always at the park with her father, Marcos Ellazar, and her brother. When Skylynne Ellazar was 10, she was a cheerleader for her brother’s football team, too.

“What would you rather have?” her dad asked one day. “People cheering for you or [you] cheering for people?”

Soon after, when Marcos Ellazar dropped her off at cheerleading practice, he received a call from her coach telling him to come back. His daughter wanted to go home.

From then on, softball was all she focused on.

“Because of her brother and his work ethic,” her dad said, “that kind of got into her, too.”

‘BEFORE MY EYES’

When Ellazar was 14, her dad left her with her mother while moving his father into a care home. Not long before, he and Ellazar’s mother had divorced, and she “took it really hard.”

On the second day of his trip, his friend, who rented a room from his house, called.

“Hey,” the friend said, “your daughter just crashed your truck.”

Ellazar had found her dad’s keys and went for a joyride with her friend. It ended with the truck totaled after rear-ending a car. Marcos Ellazar, furious, planned to fly back the same day, though he was relieved his daughter wasn’t hurt.

The truck was two years old and uninsured — it was canceled after the divorce. Skylynne Ellazar wanted to quit softball and get a job to pay her father back, but he refused.

Ellazar matured after the crash, her father said. They grew closer while he worked about 16 hours a day to make up the money. They knew if she stayed focused, Ellazar would have a chance to play in college.

“Life flashed before my eyes a little bit,” Ellazar said. “It changed pretty much my whole outlook on what I needed to be doing and what was important.”

“Her work ethic,” her dad added, “was unreal.”

CALIFORNIA DREAMIN’

That drive propelled Ellazar’s rising success on the field.

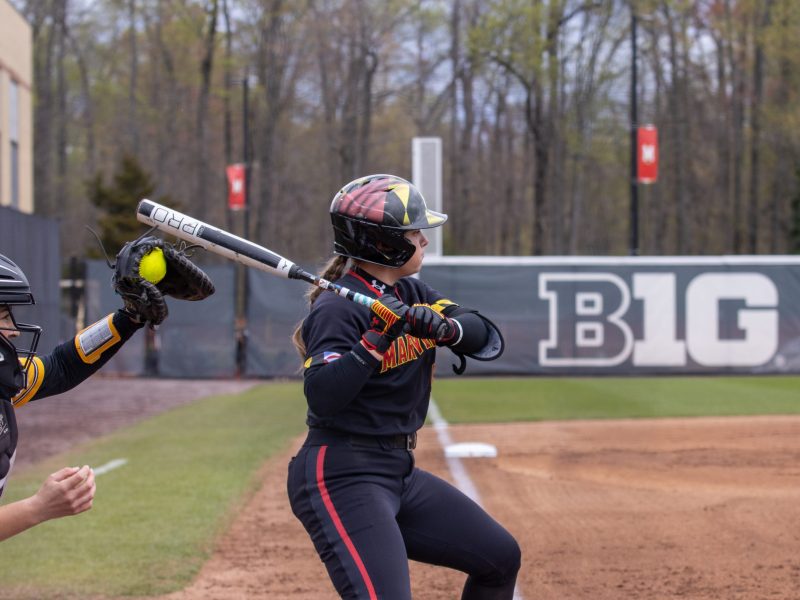

She was a natural right-handed hitter but switched to left as a high school freshman. That caught the attention of the California Cruisers, an Orange County-based squad, who had a connection to a former Hawaiian player and were looking for a lefty slap hitter.

So, she flew to California for a weekend tournament during the fall of her freshman year and made the team. She played each summer until she graduated.

She stayed with Cruisers assistant coach Dill Jaquish’s family and became best friends with her teammate, Sahvanna Jaquish, who now plays at LSU.

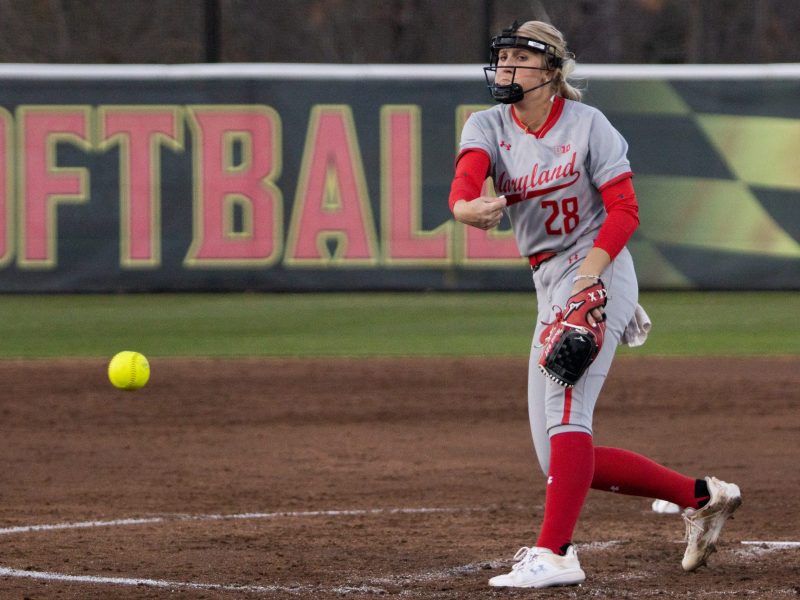

Maryland pitcher Hannah Dewey and Ellazar played together on the Cruisers for about three weeks as Dewey was staying in shape before joining the Terps. She witnessed the Ellazar-Jaquish friendship firsthand.

“It was like you guys were sisters,” Dewey said, sitting next to Ellazar. “It was the tough love, just because that’s how both of them are. They’re both super stubborn, very outspoken, but in the best sort of way.”

When Dewey first met Ellazar, she was shocked by her commute.

“You fly in a girl from Hawaii to play on your travel team in the summer?” Dewey asked. “That’s unheard of.”

But playing only in the summers put Ellazar at a disadvantage. In California, travel seasons are year-round. Division I scouts didn’t go to Hawaii to see Ellazar play for Baldwin High School.

“My biggest setback was being from Hawaii,” Ellazar said. “A lot of people use it as an excuse because we do not get exposed as much as the other kids.”

The summer before her high school senior year, Ellazar didn’t know whether to return to California. It was expensive, and while she garnered college attention, the offers didn’t entail much scholarship.

The Jaquish family, however, promised to lend financial support for her final travel season.

“They took care of Skylynne like their own,” her dad said. “I’m a single dad, and [Jaquish] said ‘Send her up here, don’t worry.'”

‘WHAT? NO WAY. MARYLAND?’

While playing in California, Ellazar focused on the PAC-12. She almost signed for UCLA after practicing with the team for half a week, but her father told her to wait. The Bruins wanted Ellazar as a walk-on.

The next week, former Maryland assistant coach Amber Jackson came to a Cruisers practice. She watched Dewey and was also interested in the team’s catcher.

But after watching Ellazar workout, Jackson went to Ellazar’s coach and said, “I want her.”

“What?” Ellazar remembered saying. “No way. Maryland?”

Ellazar knew Dewey had signed for the Terps and remembered Shannon Bustillos, a former Cruiser and Maryland player, visited over the summer, but the school didn’t cross her mind until Jackson pushed her initial interest.

Jackson followed the team to Reno, Nevada, to watch the Cruisers play a tournament in 2013. In the first game of the series, Ellazar peered into the stands and saw the coach. Jaquish hit behind her and noticed Ellazar’s glance.

“Just do you,” Jaquish said.

In Ellazar’s first at-bat, she hit a home run. In her second, she had a double. She was “seeing the ball like a watermelon.”

Jackson called Ellazar that night to promise an offer by Friday.

“Maryland wasn’t fooling around,” her dad said. “By Friday, they had an offer.”

The two agreed it was a good option, and Ellazar wanted to attend a school in a big conference. Plus, her dad likes to travel and was eager to visit the East Coast.

“You know what Sky?” Ellazar asked his daughter. “I don’t even know where the University of Maryland is. Did you look it up? … Because you’re going, not me.”

‘A BIG THING’

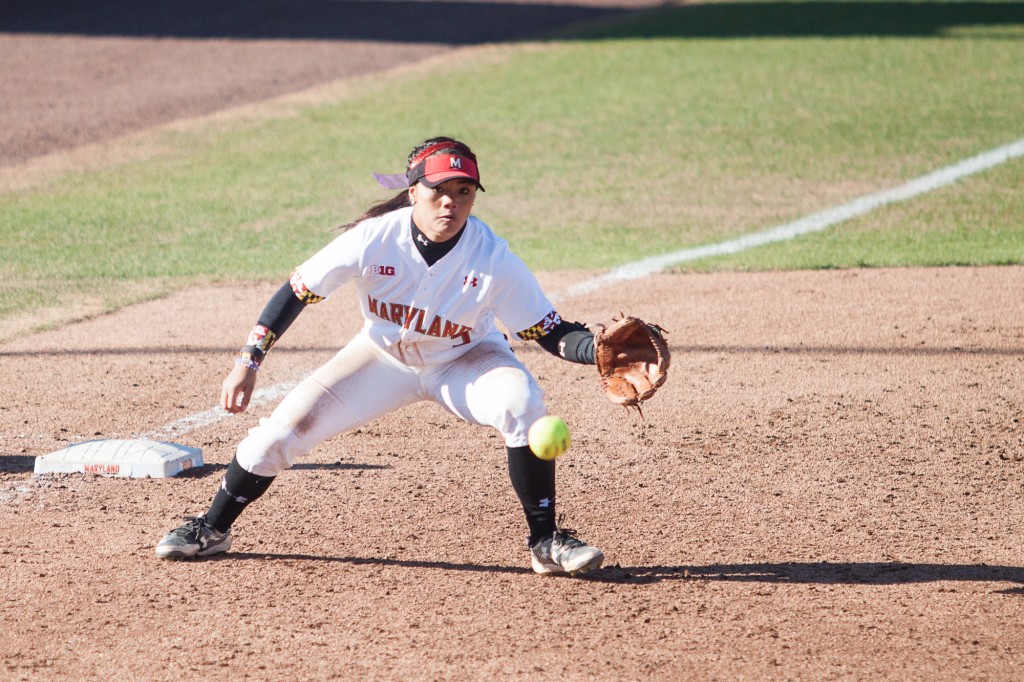

Three years into her career in College Park, Ellazar has become a cornerstone in coach Julie Wright’s rebuild. As a sophomore, she held the third-highest batting average in Maryland history (.399). This year, she’s started all 40 games and had the third-most RBIs.

When she returns to Hawaii during breaks, she tries to instill a work ethic in upcoming prospects. She works with youth teams for free, just like the help she received from her mentors.

“A lot of kids are afraid to leave,” Ellazar said. “They get homesick; the culture is different.”

But Ellazar is an example for possible achievement.

In a year, she plans to graduate from Maryland with a criminology and criminal justice degree, one of her main goals when she embarked on her rigorous journey through the sport.

“That’s a big thing in Hawaii,” her dad said. “A local girl goes out there and goes to school four years and graduates.

“Everything happened for a reason, [but] it happened in strange ways.”