Para leer este artículo en español, haga clic aquí.

The zoning rewrite working its way through the Prince George’s County Council shouldn’t significantly alter housing and development in College Park, but it could raise housing prices in nearby Langley Park. In light of the proposed changes, activists and experts say there’s a need for affordable housing across the county.

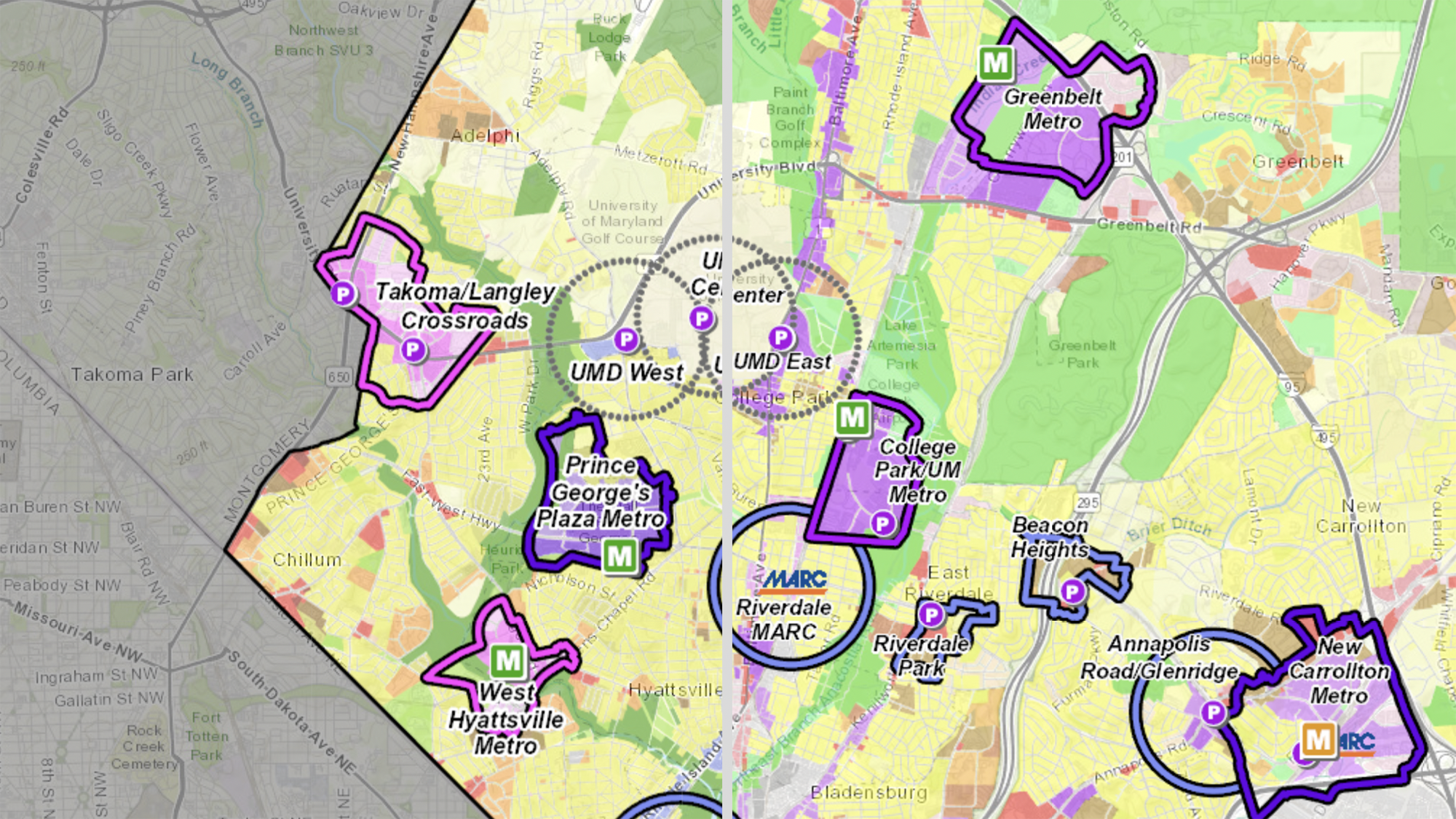

Known as the countywide map amendment, the zoning rewrite aims to modernize the current zoning code, which is about 50 years old, and make it more understandable. The new zoning ordinance, which was adopted in 2018 and is slated to be effective once the county approves the map amendment in November, aligns with the county’s focus to prioritize development around major transit, such as the Purple Line and the Metro, according to Cheryl Cort, policy director for the Coalition for Smarter Growth.

Zoning laws tell municipalities where development is allowed and what type of development can be built. In Maryland, most municipalities don’t have control over planning and zoning — all decisions are made at the county level. While cities can support or oppose new development, they ultimately have little say in the final product.

The new zoning ordinance proposes changing some development standards in College Park and “upzoning” in Langley Park — increasing the value of existing property and allowing for more units within a certain space — because of the Purple Line. As a result, developers can take over these properties, and charge higher rents, said Dr. Willow Lung-Amam, an associate professor in the urban studies and planning program and director of community development for the National Center for Smart Growth Research and Education at the University of Maryland.

“Those are the kinds of moments where questions of affordability really come to the floor,” Lung-Amam said. “It is increasing the possibilities of what can happen in those areas, and it should come with some strings attached for developers.”

Activists such as Ashanti Martinez, a research and policy analyst at CASA, a grassroots immigrant advocacy group, have voiced concerns about rising rents in the county as a result of increased development. The county council has not adopted policies such as inclusionary zoning in the rewrite, which would explicitly price some units in new developments below the market-rate.

“It’s a disservice to the residents of Prince George’s County that we’re not looking at our zoning as a way that we can help produce more affordable and equitable housing options,” Martinez said.

[Businesses settle into Discovery District to hire young professionals, promote vibrancy]

Last year, Prince George’s County concluded that an inclusionary zoning policy around Metro stations was not feasible due to market conditions. Neighboring Montgomery and Howard counties currently have these types of policies in place.

The county experimented with inclusionary zoning in 1991. Just five years later, county officials repealed the ordinance, citing that they felt the county had more than the region’s fair share of affordable housing.

Now, Prince George’s County is one of the most wealthy African-American majority counties in the country. But issues of affordability persist.

“Our metro area is one of the lowest income counties with the highest percentage of affordable housing and other kinds of indicators of inequality,” Lung-Amam said.

Terry Schum, College Park’s planning director, said the proposed zoning laws would not drastically change development in College Park. If anything, she said, they would enable slightly less density, because of the replacement of more broadly applied overlay zones with less flexible infill zones.

Still, College Park City Council member John Rigg said an affordable housing strategy that acts like inclusionary zoning would be welcome.

“There are places like [the] city of College Park where rents are higher, noticeably higher than they are in the rest of the county,” Rigg said.

In College Park, the goal is to increase the supply of housing in order to meet demand, which should theoretically drive down rents, Rigg said. But experts don’t foresee housing demand decreasing any time soon, and developers are not incentivized to charge lower rents.

While the city council recommended in March 2020 that the county change proposed zones to local transit-oriented zones to incentivize development, the zoning designations put Langley Park tenants in older apartments at risk.

Many of these complexes lie in proposed local transit-oriented zones, which aim to increase neighborhood density around transit. Many residents in these apartments are CASA members, said Trent Leon-Lierman, Maryland organizing lead at CASA

“We want to make sure that developers do not profit off of their displacement by … [building] fancy new apartments that nobody that currently lives here would be able to afford,” he said.

Currently, the county has a large stock of market-rate apartments and single-family homes, but less housing for younger professionals that the county is looking to attract, housing for older residents and deeply affordable housing, Lung-Amam said.

“The county has a little reckoning to do in order to really provide a diversity of housing types to meet its needs,” she said.

[Students have decried College Park housing costs. New apartments could worsen the issue.]

Without plans for inclusionary zoning, there are still other ways to address the lack of affordable housing in the area.

For one, the county could pour more money into its housing investment trust fund, which would set aside money to subsidize apartments and offer lower rents, according to Leon-Lierman. This solution would provide benefits throughout the county, not just in Langley Park.

CASA and the Center for Smart Growth Research and Education have also proposed changing the zones in Langley Park to neighborhood activity centers. This would allow for some neighborhood growth but would prevent gentrification by ensuring existing housing is not torn down.

Leon-Lierman also stressed that increasing neighborhood density wasn’t necessarily undesirable — denser communities can provide better access to community centers and transit that lower-income communities can take advantage of. But the specific situation in Langley Park called for some tenant protections.

“In this particular scenario, we weren’t supportive of zoning without concessions from developers and some safety mechanisms that would prevent gentrification of the area,” Leon-Lierman said.

In terms of getting their proposed changes implemented in the code, Leon-Lierman and Martinez are hopeful that the county council will be receptive.

“There is a willingness to incorporate the community’s concerns, and I think there is a willingness to be as thoughtful as possible during this process,” Martinez said. “The county is finally in a position where they’re understanding that if we want to be leaders in the region, that we have to have a diversified housing market.”

But despite constant efforts by activists to mitigate gentrification and rising costs, zoning laws won’t be enough to address these concerns.

Lung-Amam has concerns that without both proper affordability protections and increased density, the county is headed toward a trend seen in regions such as the Bay Area in California, where levels of unaffordability prevent many people from living in the area.

“What we’re seeing right now is that our whole region has become extremely unaffordable,” she said. “Inclusionary zoning only works when development is happening.”

In College Park, that increase in development is occurring, but mostly only of market-rate housing. Rents have continued to increase, and the development of the Purple Line, the Metro and the Discovery District, this university’s research park, might further drive up demand in both College Park and Langley Park.

Zoning is just one tool to help solve the affordable housing problem, according to Lung-Amam. Solutions to this nuanced issue will require action on the side of both municipalities and the county.

“We must do more to control rising rents, to maintain affordable housing, to empower tenants to have a say in where and how they live,” Leon-Lierman said.