The conclusion to the latest phase four installment of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, was political yet action packed. While there were tacky moments, Marvel addressed heavier issues like the erasure of Black history, stubbornness of politicians and difficulty of coming back from a tough past.

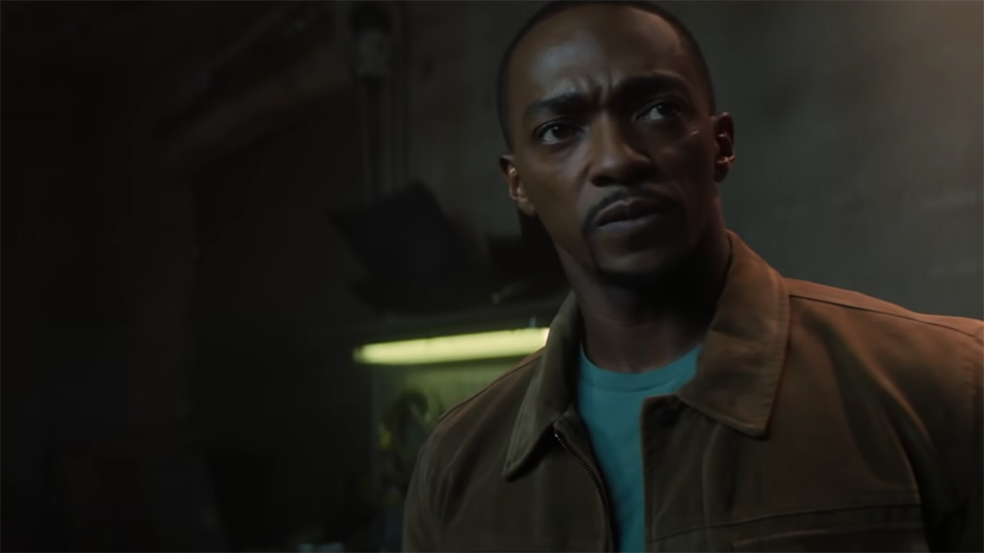

Our main characters are two familiar Marvel Universe staples: Sam Wilson, a former airman whose specialty is using a mechanical wingsuit that allows him to fly like a bird, hence his superhero name “The Falcon,” and James “Bucky” Barnes, a villain-turned-hero World War II veteran who was captured by the Nazi organization Hydra and brainwashed to become the Winter Soldier.

The Falcon and the Winter Soldier was originally supposed to premiere before Wandavision, but when the pandemic hit, the order was switched around. The pandemic has also affected the release of other Marvel productions, like the Black Widow film, which has been postponed for over a year now.

I watched all the fan theories for Wandavision as more were revealed week by week, but with Marvel’s second Disney+ release this year, I’ve preferred to watch it unfold without much outside speculation. The Falcon and the Winter Soldier has been like watching a continuous Marvel movie, whereas Wandavision genuinely felt like it was split into pieces.

[“No mourners, no funerals”: Will Netflix’s adaptation of ‘Shadow and Bone’ be a success?]

The dynamic between Wilson and Barnes was entertaining. They both had angst related to Captain America’s death, feeling left behind and confused with what the Captain’s vision for them was.

For Wilson, it’s a fear of inheriting the title of “Captain America.” He faces discrimination, even as a well-known superhero. In the series, he is stopped by the police in Baltimore and denied a loan in his hometown, despite being asked for a selfie by the loan officer.

Wilson meets Isaiah Bradley, a Black super soldier who was experimented on, imprisoned and eventually wiped from history, despite the fact that he could have been a Black Captain America. I loved how Marvel balanced Bradley’s skepticism of institutions with Wilson’s passion for justice.

“I’m a Black man carrying the stars and stripes,” he said in the finale. “Every time I pick this thing up, I know there are millions of people who are going to hate me for it.”

Marvel doesn’t steer away from directly addressing these racial issues — albeit at times I worried it was a bit performative. Whether that’s the case, Wilson still ends the series confident, empowered and bearing the title “Captain America.”

Barnes’ storyline was also heart-wrenching. He’s bitter, only half buying into his therapy treatments as he attempts to reconcile with who he used to be. At one point, Wilson called him out, saying “you weren’t amending, you were avenging.” His growth by the end of the series was fulfilling, tying off his villain-turned-hero arc.

The antagonists were probably the worst written part of the show. They were rushed and eye-roll predictable. We have John Walker, an overly cocky and aggressive soldier whose only role is to become a nuisance in future movies. Marvel’s love for fight sequences overpowered his personality and, while his introduction to the universe was intriguing, I couldn’t help but feel he was forced into the story.

Sharon Carter, a S.H.I.E.L.D agent — who also happens to be Peggy Carter’s niece — makes a return too. I wasn’t surprised by the fact that she was a mysterious and menacing “Power Broker.” The writers of the show should’ve just screamed that from the first of many walking-and-talking on the phone scenes.

[The European Super League tried to put fans last and no one bought it]

I strongly disliked Erin Kellyman’s character, Karli Morgenthau. Her justification of her behavior wasn’t believable. How could she love children and care so deeply about the people around her without being able to see that she would be killing others’ loved ones? The show tried to make Morgenthau fall into a morally grey song and failed miserably.

Her group, the “Flag Smashers,” aimed to return society to how it was before half the world was snapped out of existence. She stages several attacks on politicians who she feels just aren’t listening. Wilson eventually sees reason in her request to get the government to care about the people they left behind, but it still leaves me wondering why she thought bombing these organizations to “prevent a vote” would fix anything in the long run.

Other than that, The Falcon and the Winter Soldier felt grounded in reality. It was almost like we were living in the same timeline. This is a society that’s rebuilding and reconciling. Superheroes have people problems and, sometimes, villains have valid reasons to be villains.

“The only power I have is that I believe we can do better,” Wilson said in his final monologue. “We can’t demand that people step up if we don’t meet them halfway.”