A gang of biologists, engineers, physicists and neuroscientists walk into a lab.

What sounds like the start of a bad joke is actually the foundation of a new research project at the University of Maryland that employs an academically diverse group of scientists — and a whole lot of crawfish — to better understand the relationship between the brain and the gut.

This unlikely group was brought together by a three-year $1 million grant from the National Science Foundation. The research they conduct could influence current understanding of how serotonin production in the gut affects disorders such as depression and anxiety.

Serotonin — a neurotransmitter known for its connection to feelings of happiness and well-being — is mainly produced in the gut, said Ashley Chapin, a bioengineering doctoral student involved in the study. This is why diseases involving inflammation of the digestive tract are often accompanied by mental health difficulties.

“[The project] sort of marries the idea of nutrition having a really strong impact, not on just your [physical] health, but also your mental health, and vice versa,” Chapin said.

[Read more: These UMD researchers are helping farmers grow crops on urban roofs]

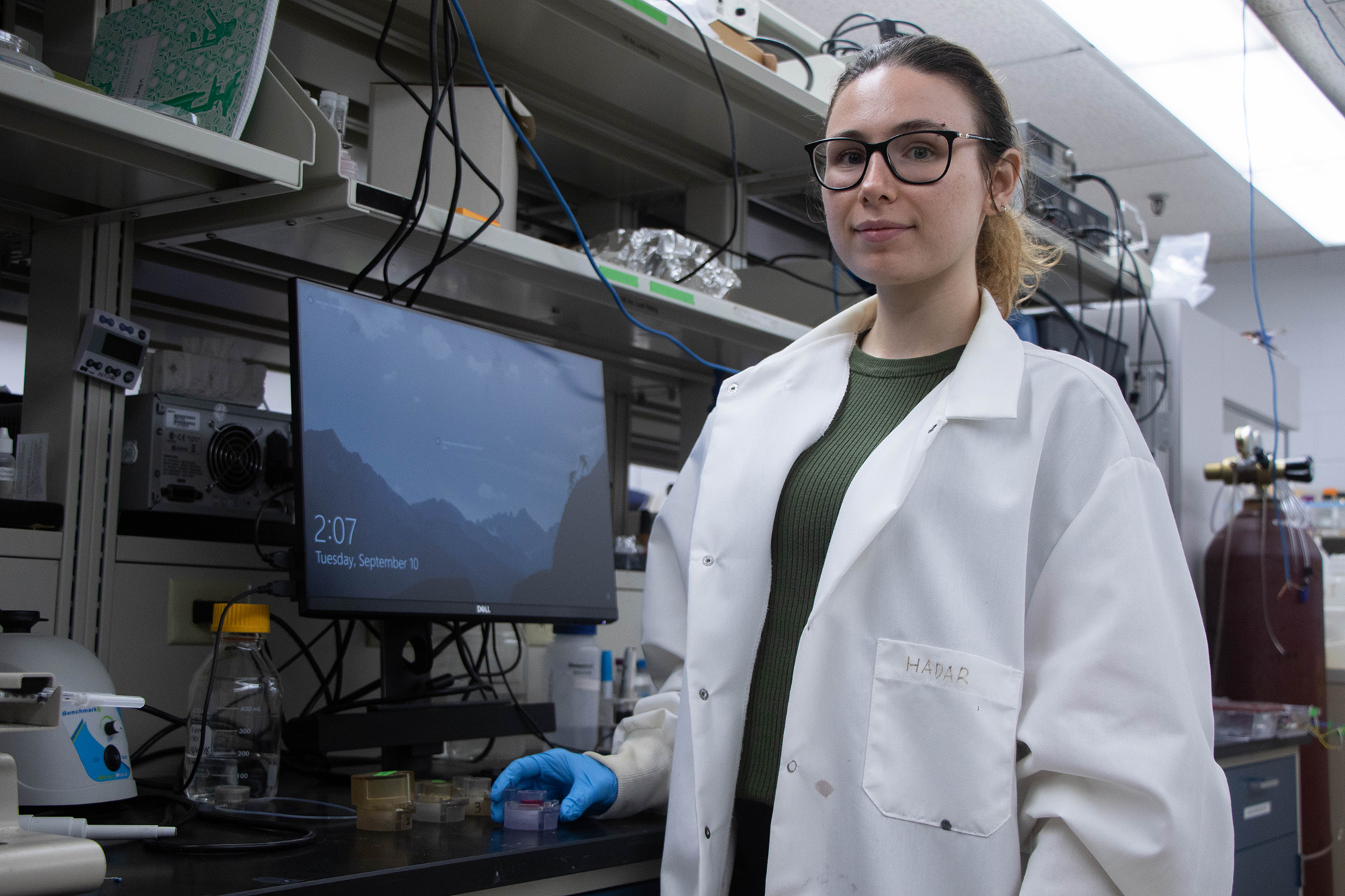

For the study, Chapin built a model of a gut lining to which she attached electrodes to monitor the generated serotonin levels.

She used three types of cells that are present in the lining of actual guts to build the model, but she’s primarily concerned with the type of cell that produces serotonin: enterochromaffin cells. These cells also stimulate the enteric nervous system — a system embedded in the walls of the digestive tract that is often referred to as the second brain.

Apart from its connection to happiness, Chapin said serotonin acts as a biomarker for disease and could potentially give insight into underlying causes of ailments and disorders.

Cells communicate through signals, Chapin said. Her research sets out to understand the signaling between the brain and the gut.

“What we’re trying to do is just make little electrodes that can easily be placed in the right spot of where those molecules are being sent so we can listen in,” Chapin said.

[Read more: A UMD student is working on a device to curb unnecessary toilet-flushing]

Sangwook Chu, a postdoctoral research associate who works in the same lab as Chapin, said much of their work involves electrochemical sensors, which are devices containing electrodes.

“We are engineering our sensors that can really be located, positioned at those sites so that we can acquire more specific information in terms of time and location-wise to help better understand the time and the signaling between the gut and the brain,” Chu said.

Outside of Chu and Chapin’s lab, Jens Herberholz, a co-principal investigator for the research, is tackling gut and brain interaction through a different lens — and a different species. He is monitoring serotonin levels in crawfish.

Herberholz, a psychology professor, isn’t studying crawfish because they’re his favorite animal, though he is quite fond of them. Instead, he’s studying them to inform studies of human behavior, even though the crustaceans don’t directly translate to humans.

Herberholz said studying crawfish behavior and serotonin levels could offer insight into the relationship between the nervous system function and gut dynamics — something he said is poorly understood.

“There’s almost like a blank box between gut and brain,” he said.

Crawfish have a long history in scientific literature, especially when it comes to understanding aggression and decision-making, he said. The crustaceans’ aggressive behavior is noticeable in any tank, Herberholz said.

This project is Herberholz’s second time working with engineers. He said he was excited about the academic diversity.

“This combination of expertise, that’s really a first for me too,” Herberholz said. “I think everyone contributes something to this that will, as a whole, make this a very, very interesting project.”

CORRECTION: Due to a reporting error, a previous version of this story misidentified Jens Herberholz as director of the university’s neuroscience and cognitive science program and misspelled his surname. This story has been updated.