Views expressed in opinion columns are the authors’ own.

Many current college students, including myself, were lucky enough to escape PARCC testing, which Maryland phased in for third through 10th graders in 2014. But those of us with younger siblings or friends in the state’s public schools have heard the PARCC horror stories about teachers forced to take hours out of classroom time to shuttle their students to arduous, computer-based testing covering material that students didn’t learn in class.

Students across the country have complained, published their concerns and organized walkouts in protest of the testing. With all of that in mind, the state’s recent decision to stop PARCC testing in public schools starting in the 2019-20 academic year is a good move for students, and will make room for new spending priorities and evaluation methods that will help the state achieve its academic goals.

Maryland adopted the Common Core State Standards in 2010 to be evaluated by an assessment run by PARCC, an acronym for Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers. The Obama administration developed the Common Core standards to help schools measure their progress in preparing students for college and careers, and to compare that progress across state and district lines.

As a whole, Common Core and PARCC testing have met some of their stated goals but failed miserably in others. Standardized tests like the SAT and ACT can be predictive of a student’s academic success in college. Most importantly, test data helps educators and researchers concretely illustrate academic achievement disparities between white students and students of color, spurring educational reforms.

We certainly see those disparities in Maryland’s PARCC testing results. In 2018, only 41.6 percent of third through eighth graders passed the English PARCC test statewide, while only 17.5 percent of students in Baltimore City passed. Racial gaps are consistently evident in testing results — black students regularly perform lower than state averages.

The question is, are those disparities because of the students, or because of the tests? Rather than helping educators improve academic disparities among their students, PARCC testing has been accused of being racially biased at its core.

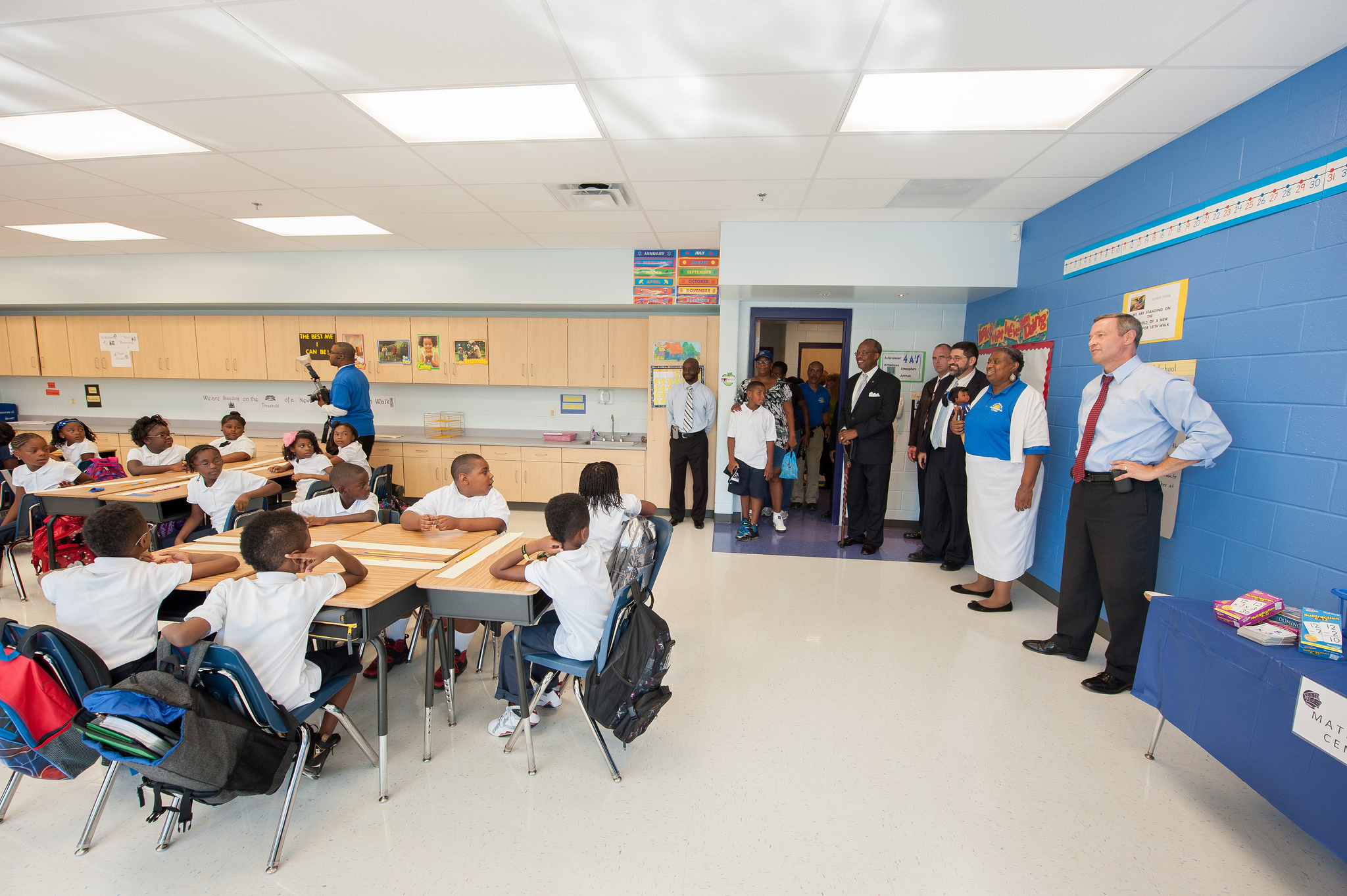

Since PARCC exams are now required to be administered on computers, students in underfunded schools who don’t use computers as often are at a disadvantage compared to their privileged, computer-savvy peers.

Racial bias isn’t the only potential problem with the data. Since fewer than 10 states use the PARCC assessments now, there is not enough data being collected to serve the test’s initial purpose of comparing school systems uniformly across the country. Maryland might as well save its time and resources by joining the PARCC-dropping bandwagon.

Yet as ineffective, disruptive and draining as we know standardized tests are, states are still federally mandated to administer them. Instead of going with stated plans to develop a shorter, less disruptive test, the state should take this opportunity to innovate in the way they evaluate their students, consulting teachers, students, parents.

Above all, the government should invest in improving the quality of students’ educations in ways that can’t be measured on standardized tests, such as renovating existing schools to provide heat and air conditioning, removing unsafe lead and mold and raising teachers’ salaries. Those kinds of investments in student well-being would free both teachers and students to focus on what matters: learning.

We don’t need a test to tell us which schools are underfunded or which schools have high minority populations. We need a commitment from Gov. Larry Hogan to target and redistribute the states’ resources to improve educational quality for all Maryland students.

Olivia Delaplaine is a junior government and politics major. She can be reached at odelaplaine15@gmail.com.